An impressionistic outlet for some of those thoughts, musical and otherwise, I don't have a chance to air in the media

Saturday, 7 October 2017

Puccini's Café Momus at the Frontline Club

...where the food is possibly better. One of the delights of hosting my Opera in Depth course at the marvellous Frontline is that we can choose our menu from the downstairs restaurant, open to the public, and consume it in the comfort of the club room, with maître d' Tomas, for whom nothing is too much trouble, to tend to our every need. Pictured above: Simona Mihai's Musetta presents her knickers to Mariusz Kwiecień's Marcello at Covent Garden, image by Catherine Ashmore.

Anyway, it's finally time for the new 'academic year', starting later than usual this time - on Monday afternoon, the 9th, to be precise, the first term then running straight through to before Christmas. Richard Jones's Royal Opera production of Puccini's La bohème has been in full spate for some time now, but I chose to spend five weeks on it (again!) because he's vouchsafed to come and talk to us (also again, after fascinating chats on Die Meistersinger, Gloriana, Der Rosenkavalier and Boris Godunov). I hope he still will since in my Arts Desk review, I had to be honest and say that, in the first-cast realisation at least, this didn't strike me as one of his more unusual shows. I know he believes, as any director with any sense should, that Puccini and his librettist leave the minutes details for the scenario and you shouldn't mess with that. But there were some less than fully realised characterisations in the first run, and the Momus act was - again, very surprisingly - a bit of a mess. Troubles with lack of lighting rehearsals, I understand, didn't help.

My second choice in the Autumn term, Musorgsky's Khovanshchina, was made on the strength of realising for the first time what a total masterpiece Shostakovich's performing version is, thanks to Semyon Bychkov's magnificent Proms performance, with a superb cast - possibly my favourite Prom of the year, though it's been very hard to choose (Bychkov pictured above at that Prom by the peerless Chris Christodoulou - don't miss his annual gallery of conductors in action on The Arts Desk). Students can see the WNO production if they're prepared to travel.

Spring operas: the first of four January Ring instalments to tie in with Jurowski's Wagner cycle at the Royal Festival Hall. Das Rheingold will take us into February, and then - finally! - I get to cover Janáček's From the House of the Dead since it's being staged at the Royal Opera for the first time (WNO also has a production coming soon). Best news of all is that Mark Wigglesworth is to conduct in place of the capricious Teodor Currentzis, so we can (I hope) welcome Mark back quicker than we expected.

Summer will see plenty of moonshine in Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream and Strauss's Salome, for which I have renewed appetite having been very impressed by the theatrical room devoted to it, and Dresden in 1905, in the Victoria & Albert Museum's stunning exhibition Opera: Passion, Power and Politics. There's the room below, picture courtesy of the V&A, but read my review on The Arts Desk today to find out why everything works.

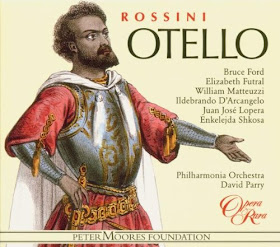

It's been a long time away from lecturing, but to warm up I got to talk to members of the Art Fund at the Royal Over-Seas League last night. This was in connection with the V&A show, but by the time I had to give a clear theme, the details of the exhibition weren't clear. So I thought a general look at how opera swung from strict dramatic principles to display, and back and forth until the end of the 19th century, would allow me to sneak in something of Strauss's Capriccio before homing in on the difference between two Otellos: Rossini's in 1816, and Verdi's in 1887: from bel canto to pure music-theatre. The two scene settings, Willow Songs with Prayers and very different treatments of the fatal last encounter between Otello and Desdemona followed by Otello's suicide would permit some interesting comparisons - not always to Rossini's detriment, though Verdi's penultimate opera is, as we rediscovered with awe during our five weeks on it for Opera in Depth, the perfect masterpiece.

This Opera Rara set is a good resource - negatively for wicked entertainment, showing how not to depend on a tenor who may have the very high notes needed for the daft role of Rodrigo but no musicality whatsoever, positively for Bruce Ford and Elizabeth Futral, and for including an appendix which even gives us the later lieto fine or happy ending drawn from a duet and an ensemble in other Rossini operas.

Needless to say there wasn't nearly enough time to play all the examples I'd intended, but it was crucial to end with the very fine filming of Elijah Moshinsky's Royal Opera Otello with Domingo and Kiri. Not possible to go and see Kaufmann when we were focusing on Domingo on the opera course earlier this summer - and it's very hard for anyone to come anywhere near to Domingo, who simply owned the part.

As I think audiences on both occasions very much agreed. This is the only Otello you'll ever want on DVD, though the choice is wide indeed when it comes to CD (Toscanini, Levine, Karajan with Vickers and Freni, live Carlos Kleiber for starters).

If you're still interested in attending the Opera in Depth course either this term or later, do drop me a note by way of a comment here - I won't publish it, and if you leave me your e-mail, I'll respond.

As human beings we cannot help emotions and sometimes strong emotions rising within us. But the world would be a happier place if we inspected each emotion and decided on rational grounds whether to indulge that emotion or not. Othello allowed his emotions ( love, jealousy) to take him over, producing a moral fault in himself and the death of Desdemona. Often the result of emotional self-indulgence are more serious. Should not one of the basic elements of an analysis of the play or the opera be whether Othello is to be condemned for this moral fault?

ReplyDeleteYour main criterion, I believe, is whether a work of art has something valuable to say about the human condition. One of my students is a psychiatrist and made an interesting contribution at the Frontline by talking, and answering questions, for a quarter of an hour on 'Othello syndrome', the condition of pathological jealousy. In examining the play many moons ago, we agreed that the key to Iago's success is to play upon Othello's ignorance of Venetian customs. The outsider status definitely has a part in all this, which is why race and (former) religion matter. Anyway, it's not so much a moral fault as an irrational one. We would certainly challenge his statement that he is 'one not naturally jealous but, being wrought, perplex'd in the extreme'.

ReplyDeleteYes, excellent. It is only in the case of the great works of art that an analysis of the human predicament comes to the fore - indeed it defines the fact that something is a great work of art. Neither Hamlet nor Crime and Punishment is only a story. A picture by Rembrandt is not only a portrait. In an opera the plot is the skeleton, the analysis is in the music. I suppose that one could compare the two Othello operas on this basis.

ReplyDeleteVerdi was very strong in suggesting that, whatever else could be said about him. he could not be accused of not understanding Shakespeare

Which of course meant that of all his early operas Macbeth is by far the most dramatic and singular. Then there's Rigoletto, in which the central figure has something of Lear about him (remember Verdi thought of that subject, too). And Don Carlo is his homage to the history plays, the public and the private in striking alternation.

ReplyDeleteMacbeth is by far the most straightforward plot of Shakespeare's four great tragedies The psychological analysis is paramount in Hamlet, Lear and Othello. In Macbeth it is part of the plot but a man and woman might well have behaved in the same way even if they were different people ( though still ambitious of course).

ReplyDeleteHave I mentioned before that to call the play " The Scottish Play" is a rule IN a theatre, not in general use in the world?

And that, of course, is why Verdi was right to tackle Macbeth in his earlier years. I've seen several superb productions of the opera (Richard Jones's and Tcherniakov's top of the list) but none, so far, of the play. The most recent one, though visually striking, had a dreadful performance from Anna Maxwell Martin as Lady Macbeth.

ReplyDelete