It hardly seems now that it happened, but for the last quarter of an hour of Tuesday's Private View of

Charles I: King and Collector at the Royal Academy of Arts, some of the greatest paintings in the world were available to see with no-one else in the rooms. The above, of course, is Mantegna's

Triumph of Caesar, shipped to England from the Gonzaga Collection in 1630, which you could usually see in Hampton Court Palace, but not, of course, like this. Even when I first walked round, there was still plenty of opportunity to get close to the pictures - the clusters of mostly suited gentlemen weren't exactly crowding them out.

But maybe I'm being a bit childish in my delight. The main thing to say is that this must currently be the greatest collection of paintings, sculptures and miniatures on display in the UK apart from the one in the National Gallery, even if it only takes us, for the most part, from the Renaissance up to the 1640s. It has been not entirely jokingly suggested that there should be a portrait of Cromwell here too, without whose intervention and breaking-up of the collection - a Titian Cromwell gave to a plumber is going on show in Sotheby's New York prior to sale - a good many of these masterpieces would have been lost in the Whitehall Palace fire.

Even Room I, 'Artists and Agents', has one gasping. The agents are on the left wall, the court artists on the right in three magnificent self portraits by Rubens, Van Dyck - the adorable one with the sunflower - and Daniel Mytens (also good in this one, by the way).

The bust of Charles dead-centre is thought to be a copy of the one by Bernini lost in the Whitehall fire. It allows for what I hope is interesting composition among the few photos I took (I asked a warden if I was allowed to photograph without flash, and he genially replied 'you can photograph any way you wish, for this one night only'). For I'm assuming that the usual rendering of Van Dyck's Carolingian Trinity will normally be seen, as it is in the exhibition's keynote image, by itself. Fascinatingly, it was sent by Van Dyck to Bernini in Rome in 1636.

The straightforward photos of the paintings here, of course, are not mine - I wanted to show the Van Dyck at closer quarters.

Room II has the National Gallery's Correggio

Venus, Cupid and Mercury alongside the National Gallery of Scotland's Veronese

Mars, Venus and Cupid side by side, plus the grand Rubens of Venus protecting Pax from Mars (also National Gallery) dead centre.

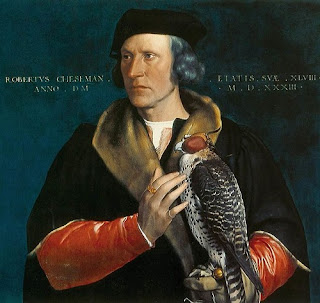

Then come the Mantegnas in the biggest room and a stunning line-up of Holbein portraits in Room IV including one of my favourites, of Robert Cheseman with a falcon, from the Mauritshuis.

A miniature gem from the Frick, Bruegel the Elder's

Three Soldiers, hangs on the opposite wall.

The three Titians side by side in Room V are, for me, the most staggering in the exhibition. Here are the two I'd take if I had a big enough palace to hang them in, the Prado painting of Alfonso d'Avalos, Marchese del Vasto, Francesco d'Avalos, addressing his troops, which has to be seen in the flesh for its grandeur and brilliance, and the Louvre

Supper at Emmaus, usually overlooked in Paris because it shares a room with the Mona Lisa.

The compassionate risen Christ here is one of the most moving imaginings I've seen, if not the most moving. And the fabric colours, the general gentle hue, also amaze. The superabundance of Royal portraits in the next room are very fabric-, as in silk-, conscious, too. I remember the portrait of Henrietta Maria always took my childish fancy in the PG Tips card series

Costumes through the Ages. The 'Greate Peece' of 1632 hung prominently in Whitehall Palace is the grandest of the set.

To balance the Titians, at not so much lower a level of quality, Tintoretto's

Esther before Ahasuerus is flanked by two very fine Bassanos in Room VII.

Room VIII is fascinating if a little odd - those Orazio Gentileschis with their waxy but modern-looking figures - and Cristofano Allori's

Judith with the Head of Holofernes leaps out.

Then we're in the Whitehall Palace cabinet of smaller paintings, with more Holbein paintings and some of those extraordinary portraits in black and coloured chalks, bronzes, Hilliard miniatures and the Roman glass-backed sardonyx portrait of Claudius.

From small to great, and tapestries of the Raphael Acts of the Apostles, woven at Mortlake from seven of the cartoons purchased in 1623 from Genoa by Sir Francis Crane. These ones from Paris complement the ones in the V&A.

The Central Hall has a brilliant assemblage of Charles on horseback - one Van Dyck with which we're very familiar as National Gallery visitors, others less so - while the final room, where the curator was being filmed when I saw it, takes us to later achievements of Van Dyck and Rubens in England; the former's

Cupid and Psyche offers a last fling.

There. I feel breathless just going superficially through it. And as a nice coda, I got to press the flesh and feel the feathery dress of Grayson Perry. Brexit, he said, is the gift that keeps on giving for artists railing against it (I wish I hadn't known that two of our artistic national treasures are in favour of it). I told him how tickled I'd been by the display of his costumes,

Making Himself Claire, in the Walker Art Gallery on my visit to Liverpool back in November (just before I went off to the afternoon performance of

Verdi's Falstaff with Bryn Terfel and Vasily Petrenko conducting at the Liverpool Philharmonic).

He hadn't been. I mentioned the Post-It notes pictured here

and he said that if only one child became an artist as a result of having been to a gallery, it had to be worth it, didn't it?

Since I now realise I didn't get to blog about my afternoon in Liverpool, it's worth noting that the Walker has some very fine British paintings as the core of its collection. Stubbs, of course

and Gainsborough,

all handsomely hung in the recent revamp. Not so sure, much as I admire her in principle, about Turner Prize Winner Lubaina Himid's cut out slaves, part of the installation

Naming the Money, hogging some of the limelight from Hogarth's swagger portrait of Garrick as Richard III.

but the parallel between wealthy patrons and slaves is well made. Anyway, I feel that old art-hunger coming on. Sophie has proposed that we go and look at the Dante-quoting frame for Ari Scheffer's

Francesca and Paolo at the Wallace, and I have to catch the Kabakov installations at Tate Modern before the show closes on Sunday.