An impressionistic outlet for some of those thoughts, musical and otherwise, I don't have a chance to air in the media

Saturday, 19 March 2016

Andsnes, Astrup and other Norwegians

Had my Arts Desk say on the first of two programmes given by Leif Ove Andsnes (pictured above overlooked by Gainsborough ladies) and two young Norwegian musicians at the Dulwich Picture Gallery; handed over to Gavin Dixon for the second, and he did an excellent job (which means I agree with him). But I couldn't resist going back for the daytime recital, partly because I'd fallen in love with that amazing gallery again and wanted to sit with Soane's provision for natural light from above having its full effect.

On the first evening, I sat myself right alongside Van Dyck's Samson and Delilah, one of my favourite pictures in the gallery along with the three Rembrandts and a Claude.

Tuesday lunchtime was a chance to sit on the other side, so not looking towards the male nudes as in this photo of violinist Guro Kleven Hagen,

but in the opposite direction, with a whole other clutch of pictures around me. Hearing both programmes gave the opportunity to appreciate the perfect symmetries of the programming, made by Andsnes in conjunction with the cultural wing of the Savings Bank Foundation DNB - a very enlightened collaboration responsible for both the majority of the Nikolai Astrup paintings in the current exhibition and the valuable instruments on loan to Hagen and viola player Eiving Holtsmark Ringstad.

The highlight of the second concert, for me, was Ringstad's performance with Andsnes of Sinding's Suite in the Old Style: the first movement a virtual moto perpetuo in which Ringstad dropped no stitch and made musical sense of virtuosity, the second a chance to return to the dark brooding to which the viola is so suited. Diffident in person, Ringstad comes alive as a performer, a good foil to the more reserved musicianship of Hagen. As for Andsnes' inclusion of four of Grieg's many Lyric Pieces, I ordered up the disc of his performances recorded on Grieg's Steinway in the house at Troldhaugen (a pairing of man and piano which, of course, I was uniquely privileged to experience for myself in the realms of Kurtág and Liszt during last summer's trip to Bergen).

Delighted as I was to receive these photos from Dulwich Picture Gallery's press department a week after the event, I felt just a bit miffed that they hadn't taken up my suggestion to photograph the three musicians in the Astrup exhibition's final room of midsummer bonfires. The best I can do is an illicit picture of the crowds in that room - like the Norwegians, I was amazed to see so many of Astrup's flaming canvases gathered together in one space, and there were no postcards of this splendid group.

Many of these pictures I saw for the first time last summer in one of Bergen's superb KODE galleries, in a new wing specially devoted to the master; mostly denuded in the cause of the Dulwich exhibition, the biggest of Astrup's work to be shown anywhere in the world, it currently has a special display devoted to the artist's early works.

What most struck me then and, in much more detail now, was the special quality of Astrup's woodcuts. Like Munch, who bought several of his early works, Astrup proved something of a pioneer here - in fact, more so. He not only painted on his wood blocks, but also on the finished prints. He writes almost self-reproachfully about his 'experimentation', continuing:

I work in my own way, and several of my impressions can appear to be more paintings than woodcuts and this is, of course, really a fault - that is also why I have not considered exhibiting them. Some of them also require a lot of work to print, as I use 5-6 blocks for each impression.

He chose his paper carefully, linking it to his environment - he liked the Kazo of inspirational Japanese example, long-fibred stuff from the paper mulberry tree - and alder was the preferred tree for his blocks, though he also used pear and pinewood.

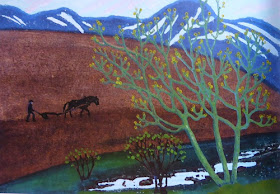

The Dulwich exhibition gives in some instances four different versions of the same scene, infinitely sensitive to the tones and changing seasons of the small area above Bergen where Astrup worked and lived for most of his life. In a rare move to please a patron fond of the marsh marigolds which feature in some of his most famous images, he reworked Night Ploughing, c.1905

to include the plant in 1927 where the water had been.

An assemblage of no less than four woodcuts of The Moon in May, 1908, which I can only suggest in their entirety from two pages of the excellent catalogue

range from an idyllic scene with two people working in the garden

to what looks like a snowy landscape with a very thick application of paint.

As for the joyous midsummer bonfire images, one famous oil with lovers, dancers and fiddler

exists both as colour woodcut in several versions

and in black-and-white, making the fiddler look like Old Nick - after all, Astrup's pastor father thought these rituals were the work of the devil.

You can see why these images are a source of no small fascination, and I'll certainly return to Dulwich before the exhibition ends on 15 May (if you want to see it after that you'll have to travel to Norway or Germany).

What ought to be more than a footnote but which finds itself squeezed in here by virtue of its link to an unusual concert in a special place has to be the second of the Waterloo Warehouse concerts organised and conducted by the ever-enterprising Jonathan Bloxham (all donations, as before to MOAS, Migrant Offshore Aid Station - and as I promised I gave all savings on Christmas cards and stamps to them as well, though a little miffed not to have had the barest acknowledgment. Anyway the transfer went through). I'm being totally honest when I say that Ben Baker's interpretation of the Beethoven Violin Concerto with the orchestra of students and young professionals was the most arresting I've ever heard. Here he is with Jonathan after the performance.

Told an exhausted J he might be able to doze at some point during the Beethoven - I often do, if only mentally - but he had cause to reproach me jovially for never at any point being able to do so. Jonathan paced the central movement just right - more a stately dance than a bland wallow - and Ben, peerless in musicianship and intonation as ever, chose the fiendish cadenzas adapted by Christian Tetzlaff from the version Beethoven made for piano and orchestra, celebrated for having timps to dialogue with the soloist at one point.

The Brahms One which followed was way too big for the modest surroundings, but a flexible and impassioned interpretation with real extra dynamism in the finale, where you noticed all the more how the themes just keep pouring out of Brahms in highest inspiration. This was just as fascinating an approach in its way as Ticciati's with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Jonathan tells me he is up for the post of assistant conductor with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he deserves to get it.

My compliments to you for this piece about Andsnes, Astrup and the rest of us. A good read. It is so inspiring for me (as well as to my colleagues in KODE) to see Norwegian art and music coming together, and even more when good people write about it with relevance and enthusiasm. I've shared on Facebook, where you have chosen not to be.

ReplyDeleteAll the best from Troldhaugen, Sigurd

Delighted that the first people I should see in Room One of the Astrup exhibition on that first evening should have been you, Leif Ove Andsnes and, was it, Anders Bjornsen who enlightened me fully on the links between the instruments and the art?

ReplyDeleteAs I think you know by now, I'm quite sincere about the indelible impression left by Bergen - above all your friendly hosting at Troldhaugen, and of course the excursion to Ole Bull's island villa. I now dream of visiting Astrup's Sandalstrand.