An impressionistic outlet for some of those thoughts, musical and otherwise, I don't have a chance to air in the media

Wednesday, 16 March 2016

Kremlinology

It's such a jolt to go back to a plain-speaking history of Russia after the selective violence of film and fiction. Eisenstein's Ivan the Terrible, for all the black-after-white menace of its Part Two, gives you no idea of the amount of blood that flowed, the piles of corpses that accumulated, in the second half of the ever more crazed tsar's rule.* Tolstoy's War and Peace treats the Great Fire of Moscow as a noble patriotic act, but offers no sense of how the fire blazed for ten days and of the carnage it caused (for the same reason, incidentally, I'm not surprised my dad would never speak of his work as a London fireman during the Second World War - we think of the spectacle of the flames, whereas what probably stuck in his mind was charred body after body).

Catherine Merridale's Red Fortress: The Secret Heart of Russia's History tells the ongoing national tragedy from the perspective of what was for centuries, and is again, the centre of power. In fact its only relatively happy times would have been the brief Russian Enlightenment after things first moved to Petersburg (and a Russian Enlightenment is not the same as a European one). Here's a view from 1800, even more peaceful than Joan Blaue's lovely 'Kremlenagrad' (sic) map of 1648 pictured up top.

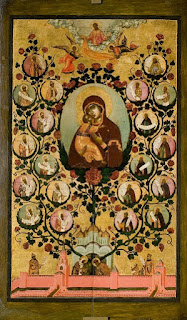

This is also a tale of faked legitimacy, the attempt to link the tsars in a line back to the Ryurik dynasty, a mythmaking transparent in Simon Ushakov's rather beautiful The Tree of the State of Muscovy (note the red-walled Kremlin at the bottom) of 1668,

echoed in the desperate ploys of usurpers in all centuries to make their claim to the throne 'right'. Merridale notes how communism tried a different kind of legality, and how Yeltsin attempted to bring back the imperial tone with the reinvention of a red staircase that had actually been destroyed in the time of the tsars.

So many millions of corpses weigh down the reader, and so much destruction of beautiful buildings, even if they were a symbol of oppression (the Orthodox Church before 1917 was, of course, the instrument of the state, as it is again). Gone is the ancient Church of the Saviour in the Forest (pictured below by Fyodor Alekseev c. 1800-10) and so many other ecclesiastical Kremlin buildings.

It's a miracle that the Dormition Cathedral and its neighbours, however much renovated, still stand. The Italian origins of what we see now are vividly brought to life. Merridale's account of Byzantine princess Zoe's journey to Moscow to be wife of Ivan III would be a good basis for a film (how very different to another screenplay I have in mind, of Marie Antoinette and family's flight to Vincennes and their return to Paris in disgrace as described by Stefan Zweig).

Zoe, soon to be Tsarina Sofiya, and her treasure-laden entourage travelled from Rome, where she had been brought up a ward of Pope Paul II, via Siena, Florence, Bologna, Vicenza, Innsbruck and Nuremberg, among other cities, to Lübeck, spent 11 stormy days crossing the Baltic to Tallinn (then Kolyvan) and then two months, mostly through dense forest, via Pskov to Moscow. Three years after their wedding, Ivan invited Aristotele Fioravanti from Bologna to design and execute a new Dormition Cathedral. So what we see as the omphalos of Moscow and all Russia is, like so much else, a foreign import.

In human terms, the splendour quickly faded (in any case Ivan III was not beyond destroying other cities wholesale). The absurd horrors of the smuta or time of troubles make for queasy reading (and helpful clarification for our classes on Musorgsky's Boris Godunov); Pleasure gardens and western fashions come and go in Merridale's picture of the Kremlin in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Then it's back to grimness, cynicism and slaughter for the Lenin and Stalin eras, when the place must have been at its absolutely gloomiest. In the stagnating era of Brezhnev, the Communist Party Hall for thousands was still in full swing, if that's the right word.

And now? Merridale concludes:

At this point in the tale, the idea dawns that it is Russia's people, rather than their leaders, who are blamed for any history of tyranny...On the surface, today's Kremlin is like an essay on that general theme. The message it conveys is hypnotic, a repetition of the obvious and the familiar. As the obedient groups walk round, it takes a well-informed and imaginative visitor to picture the things that have vanished, such as the ghosts of ancient churches, long demolished, the scorch-marks left by heavy guns, or the deep tracks, in now-buried mud, of horse-drawn carts sagging under the heavy rubble from the latest fire. The empty space where the prikazy [chancelleries] used to be, or where once there were warrens for the slaves and palace rats, may yet suggest the shades of long-dead Muscovites, some wielding clubs, some armed with fists, their hearts set on plunder, justice or the obstinate quest for a true tsar. A thoughtful visitor may picture the red flags, the crowds, the icy silence of the Stalin years. But only those who know their history will protest, despite all the romance and gilded domes, that the state whose flag is flying here is yet another new invented thing, the choice of living individuals rather than timeless fate. Its creators are not among the milling crowds, whatever the extent of the Russian people's exasperated collusion at different historical moments. The system is not even the product of some vaguely conceived collective being called the Kremlin. Ultimate responsibility, for better or worse, rests with specific people, and they have real names.

On which note, there's a fascinating speculation in Emmanuel Carrère's dazzling and complex study of the Russian maverick known as Eduard Limonov that Putin is his outwardly unsuccessful subject's double. Carrère chose Limonov because 'his romantic, dangerous life says something. Not just about him, Limonov, not just about Russia, but about everything that's happened since the end of the Second World War.' Putin, too, was 'raised in the cult of the fatherland [motherland?], the Great Patriotic War, of the KGB and the fear it inspires in the wimps of the west'. Yet he became politically skilful and devious, able to lie without blinking, in the way that Limonov never could. Interesting, incidentally, that this Russian edition with a childhood photo which could just as well be of Putin describes the book as a 'novel'. Truth too harsh?

Limonov's life has been one of paradoxes: from the artistic bohemian societies of Kharkov and Moscow to homelessness in New York, a cult literary success due to his many books entirely about himself, joining the Serbian 'liberators' (what on earth would they have made of his having been buggered by black men in American parks had they found out?), a bizarre flirtation (or more) with the NazBols, the National [Nazi] Bolsheviks whose paradoxical hippiness could only pertain in Russia,

then a brief leaguing with Kasparov as part of a more respectable but equally hopeless opposition.

The only connection between all these seems to have been a desire to be famous and an urge to fight on the losing side. Plus a remarkable loyalty to friends and lovers like his beloved Natasha.

So you can't say there wasn't a certain integrity there. Besides, Carrère is a seriously good, maybe even great, writer to guide us through all the tergiversations and interpose his own personality at times on the precis of Limonov's explicit writings. At the mid point of the book, moving the action to Paris, Carrère gives a slice of his own life, recounting Werner Herzog's crushing dismissal of the book Carrère has written, which he hasn't even read - 'I know it's bullshit' - whereupon a friend says 'That'll teach you to admire fascists'. Carrère, reflecting on the roots of fascism, continues:

I'm not talking about neo-Nazis or the extermination of presumed inferiors, or even about Werner Herzog's frank and robust disdain, but about the way each of us deals with the evident fact that life is unjust and people are unequal: more or less beautiful, more or less talented, more or less prepared for the fight. Nietzsche, Limonov, and this extreme moral stance within us that I'm calling fascist say with one voice: 'That's reality, that's the world as it is.' What else can you say? What stands against this basic fact?

'Nothing,' the fascist will say, 'but the pious lie, leftist otherworldliness, and political correctness, which is more common than clear thinking'.

I'd offer: Christianity. The idea that, in the Kingdom - which is certainly not the hereafter, but the reality of reality - the littlest is the biggest. Or the idea, as formulated in a Buddhist sutra my friend Herve Clerc first told me about, that 'a man who judges himself superior, inferior or even equal to another does not understand reality'....I think that this idea...is the pinnacle of wisdom, and that one life isn't enough to adopt it, digest it, and absorb it, so that it ceases to be an idea and instead conditions at every moment our way of looking and acting. For me, writing this book is a strange way of attempting to do that.

Curiously enlightenment, if not redemption, does come to Limonov, while he achieves a Dostoyeskyan understanding of his fellow men serving a prison sentence for opposition activity. Not only does Carrère opine that, for the first time in his life, Limonov becomes one of those who 'know where they are'; his protagonist also has a time-stopping vision of nirvana which may sound flaky as summarised here, but again Carrère considers it seriously, connecting it speculatively to Limonov's ongoing 'guidance' by a deceased Altai trapper he'd befriended.

So there we have it - not a villain, or a waster, but the portrait of a real man, nastoyashii chelovyek, as Fadayev and Prokofiev put it in the story/opera of a Soviet war hero. And infinitely more complex. As for the ongoing echoes of Stalin-era routines in Putin's Russia, the show trials which courageous individuals like Nadezhda Savchenko have mocked so impressively, read this powerful article on The Interpreter.

*In a comment below, Laurent drew my attention to an astonishing artistic comment by Gustave Doré. Here it is.

A page of The Rare and Extraordinary History of Holy Russia with illustrations by the 21-year-old Doré , its caption reads: 'Continuation of the reign of Ivan the Terrible. Faced with such crimes, let’s blink our eyes not to see anything more than the broad picture.' Genius, no?

I agree with the analysis of Russia and would refer to my entry "Putin is not like us" in my blog

ReplyDeletethewealthofthenations,blogspot.co.uk

It is likely that the first Romanov's great aunt ( I think it was) was a sister of a Rurik descendant

Gustave Doré did an illustration entitled Histoire de la grande Russie, it's a white page with one big blood red stain. You get the message.

ReplyDeleteOK, Sir David, I allow you to be a cuckoo, and of course I have read that article and concur with most of it as you know.

ReplyDeleteAs for Romanov links to Ryurik, 'likely' is all too typical. Spread the rumour around and people might believe it. Frankly, who cares? The Romanovs were no more legit than the rest of them. Boyar families all wielding their power. A wretched bunch who happened to throw up some tyrants with good ideas (though I'm sorry Alexander II got blown up).

And Laurent, your reply slipped in there - I didn't know, how fascinating. Must look it up. Says it all, unfortunately. The Yurodivy's lament goes on.

ReplyDeleteSee a site Web about Eduard Limonov :

ReplyDeletewww.tout-sur-limonov.fr

Fascinating text and, especially, photos, thanks for the link - the Limonov paradox continues...

ReplyDelete