Tuesday, 23 April 2019

Bonnard and Ruskin: diamonds and gemstones

From the big picture

to the cabinet of curiosities

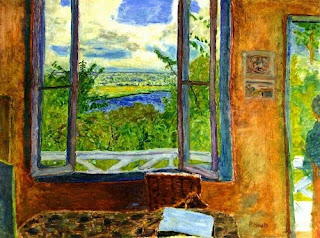

I feel enriched by two very different exhibitions. Astonished by so much critical negativity surrounding the huge Pierre Bonnard show at Tate Modern; all artists I know, including my beloved friend Ruth Addinall with whom I went, have nothing but praise for the master. What are the claims? He didn't reflect the upheavals of his times; he couldn't paint animals; it's only about colour. Stuff and nonsense. In the first case, just focus on what he did cover - mostly his various homes and women he knew well - and ask if he succeeded. My answer would be, more than I could have imagined before I visited. To catch the 'thing in itself'ness of people and animals does not require literal forms - these are forms in motion. And it's not just about colour; the ability to see different angles of a scene and to give them depth, even (this surprised me) profundity remains consistent in his work from 1907 up to his death in 1947. I loved all the works on display to varying degrees, with the exception of a few in the last room. And the very first of his Vernon rooms-and-landscapes from 1914 is a stunner, complete with dachshund.

The one so many of us know and love is from 1925, the dining room at Vernon with the dog's snout and brow just peeking above the table.

Maybe Bonnard was a god of small things, but to see into their essence is the task of genius. It helps that all these things I love so much. An airy room with pictures, a dog, a view onto nature. Coffee, too.

His nudes are intimate studies of his beloved Marthe, long-term companion, whose death in 1942 seems to have taken a lot of the elan out of his work. Again, Marthe in the bath is seen from so many different angles and there's a depth to this. Both these paintings are from 1925, but there are others just as fine from 1914 and the early 1940s.

Not a very kind segue, perhaps, to nutty John Ruskin and his horrified reaction to his wife's pubic hair on their wedding night. While Bonnard must have been genial company, Ruskin would probably irritate the hell out of you if you met him, with his ridiculous prejudices against the Renaissance, Die Meistersinger and Palladio, to name but three. But what he did cultivate in art and nature he pursued very beautifully with word and brushstroke, and the selective but rich exhibition at Two Temple Place, sadly now over, was such a joy. As is the building itself, an extraordinary late Victorian mansion commissioned by William Waldorf Astor in high neo-Gothic style which, of course, houses Ruskin rather well.

Downstairs in the exhibition, the looks were more sideways to influences than concentrated on Ruskin himself. But ascending the remarkable staircase - worth a visit in itself; it's all free - you hit two essential rooms. One is a recreation in homage to the museum Ruskin assembled in Walkley north of Sheffield, for the education of 'workers in iron' and other, concentrating on the natural history of the area. Sadly the original museum is no more, but it's been lovingly recreated in Sheffield, I believe, and this room, with the beguiling collection of minerals at its centre, was one big delight of the museum.

Then the pièce de résistance, space-wise. is the Great Hall with its Clayton and Bell windows of Swiss and Italian landscapes.

Here were lodged most of Ruskin's finest natural drawings featured in the exhibition, from the rocks of Chamonix to birds placed among representations by others (Audubon included)

including an exquisite representation of a peacock's breast feather.

So, what's this?

It's an EU-owl - the pun only works in German (EU-le). You might recognise it as the work of Axel 'The Gruffalo' Scheffler. He and other leading illustrators of children's books including Quentin Blake and Judith Kerr have responded, in the words of the blurb for the 12 Star Gallery's exhibition Drawing Europe Together, 'to make illustrated comments on the historical and possible future relationships between the countries of Europe, many of which are extremely touching and heartfelt.' Believe me, they are. And there was such a poignancy about the launch, for this was officially the last show in the 12 Star. Here's the artist speaking (I must get together more about the event, once I get hold of a copy of the book that accompanies it).

BUT. Not only are we not out, but one regional gallery decided the work was 'too political', so it got an extended lease of life. And now another, until 10 May, after Europe Day when we will be celebrating with the annual concert - here's a report of what we thought might be the last in 2018 - in St John's Smith Square (lined up whether we left on 29 March or not).

And meanwhile, here we are. Where exactly, philosophically speaking, is not clear, but still in the EU...

Saturday, 13 April 2019

Iffley on the Isis

'Isis' as in the Thames from its source in the Chilterns to Dorchester in Oxfordshire, but more specifically in the environs of Oxford. I should have followed its route years ago from near Christ Church Meadows up to this prettiest of villages - swamped at weekends, I'm told - and one of our most remarkable churches. We approached it on this occasion from the new home of our friends (and newlyweds, though far from newly together) Juliette and Rory, Fellow of Magdalen College, where he currently teaches in the Department of Oriental Studies, though soon he'll be off to take up a new post at Durham University. Very tempting that you can be out in the country within five minutes. I'd especially wanted to see Iffley Meadows which, like Magdalen, are famed for their fritillary display at this time of year, but in neither were the snakeshead bells flourishing. In fact we didn't see a single one other than in someone's front garden, but at least I'd had my vision in Kew a few days earlier.

Iffley soon looms into view with the church beacon-like above the Isis

and you approach via a series of bridges

and islets with a series of locks, an attraction in itself, before walking up the hill to the Church of St Mary the Virgin. We ended up approaching it from above, with a good view downwards to the Rectory, the ground plan of which is 12th-13th century, though its (Tudor?) brick chimneystacks are the most impressive feature from the outside.

Primroses were flourishing in the shade as we approached from the north-east what Pevsner calls 'a magnificent little church, lavishly decorated with sculpture'.

The first door you see from this side is the north one, of three from the time of the church's building (1170-80, courtesy of the wealthy St Remy family), with scallop capitals - plain compared with what's to come, though treasurable enough in itself.

Then you round the corner and are struck by the fabulous west door pictured up top. The ensemble looked like this in the 1830s

and you'll see that the Perpendicular Gothic window has now been replaced by what is deemed 'a successful reconstruction of the original Romanesque oculus, carried out by the architect and antiquarian J. C. Buckler in 1856' (the church guide I bought is superb and well illustrated, though a bit pricey at a fiver).

Not quite sure about the application of limewash to this and the south door. It was applied in 1981, with a 'new sheltercoat by Sally Strachey Historic Conservation' added in 2017.

The gable was raised in 1845; the detail around the top window is in tune with the authentic work below.

As the guide neatly describes it, 'the ceremonial doorway at ground level is flanked by blind niches with moulded arches. This doorway has three continuous orders, one decorated with chevron, one with beakheads on a spiral roll moulding and the third with beakheads on a plain roll', best seen here

and, later when the sun was fully on them, the two orders of beakheads in closer range.

Around and above are medallions containing sculptured figures and beasts, starting in the above photo with Aquarius, Pisces and Virgo. Close up on Virgo with ?gryphon? below.

In the centre, a dove (for the Holy Ghost), followed by the Lion of St Mark.

Now let's head in through that door, now the main entrance of the church. leaving J, Juliette and Rory in the sunshine on a bench where one could spend many happy hours with a good book - on a quiet weekday, at any rate (and no-one else came or went for the whole time we were there).

Looking east, the whole is of unity and a rich perspective which the photo doesn't quite capture, looking towards the sanctuary through two tower arches with Tournai marble octagonal shafts.

The first 'cell' as approached this way is the Baptistery. There's a fine unsculpted font, also in Tournai marble, and the rose window glass is fine, of 1856 by the firm of John Hardman & Co, but in tune with medieval precepts.

Much more remarkable, though, are the two contemporary artworks which fill the Romanesque windows here. In the north window, Iffley resident Roger Wagner's inspiration happily mixes Christ on the cross, a tree in May blossom and the river of life.

Especially felicitous is the flock of sheep by the river under the blossom. Very Samuel Palmerish in design if not in colouring.

Opposite it is the more famous design of John Piper, a very unusual treatment of the Nativity executed by David Walsey. At its foot there's a quotation from Christopher Smart's 'Rejoice in the Lamb' (set to music by Piper's good friend Benjamin Britten), and in this Tree of Life, the cockerel crows 'Christus natus est' ('Christ is born'), while the goose asks 'Quando? Quando? ('When? When?'), the rook replies 'In hac nocte' ('On this night'), the owl hoots 'Ubi? Ubi?' ('Where? Where?) and the lamb baas 'Bethlehem! Bethlehem!'. I'd seen a reproduction before but didn't know it was here.

I missed the Gothic angel high up in the Nave - a detail of this fine one in Oxford's oldest parish church, St Michael, which I visited the previous afternoon, will have to do -

but not the Coat of Arms of John de la Pole after his marriage in 1452-3 to Elizabeth, sister of Edward IV and Richard III (hence the Tudor rose).

Here's a view looking westwards from the tower

and beyond is the Romanesque sanctuary (now the chancel) with its fine boss at the centre of domical vault, depicting a winged serpent entwined and animal heads at each of the cardinal points, and pinecones pointing outwards towards the chevroned vaulting.

The sedilia seems to have been installed late in the 13th century, after the death of the anchoress Annora. Her cell may have been behind where the aumbry and piscina (beyond) are now.

And so out into the brighter light - though the church is far from dark on a sunny day - and to examination of the third glorious door, on the south (also limewashed).

Its fine state of preservation may be due to the fact that it stood within a porch which was removed in 1807. Here, as in the north door, there are three orders and a band of rosettes, but again the detail is fascinating. Here you might make out Samson and the lion, Ourobouros and a bird with a snake (in the slightly over-exposed middle band),

Curiouser are a merman,

a green cat (rather than a green man)

and a beast seemingly trapped behind a pillar.

And so we strolled back down to the Isis

and walked back along the other bank to lunch with Juliette and Rory, after which we went our separate ways - J in a cab to the station, I along the river this time Oxford bound, to catch the trusty Oxford Tube.

Soon the dome of the Radcliffe Camera and the tower of St Mary came in sight, with Merton Chapel's tower through the trees

and Magdalen's, the noblest, across Christ Church Meadows.

I passed Christ Church

where the previous evening we'd heard half of a superb Evensong with the choir still in residence (though university term time had ended, the cathedral school boys keep this one going). There I heard for the first time Kenneth Leighton's Mag and Nunc of 1959 (his 'Magdalen Service', no less); you hear where MacMillan, a slightly older contemporary of mine at Edinburgh University, got some of his juicier chord sequences from. The Leighton work is counterintuitive in that neither Gloria is a blaze, but they're all the better for that. And why only half a service? Because we were due at Worcester College at 7 for a dinner to celebrate the Irish presence in the Oxford Literary Festival, and I'd forgotten that Saturday evensongs are longer than the ones in the week.

So - returrning to the Sunday retreat - round towards Magdalen

and time for a quick spin around the Botanic Gardens, courtesy of my Kew card. They're slow to come to life in early spring, as I remember from previous occasions, but there are the daffs, of course, Merton tower in the distance,

some splendid miniature tulips on the Alpine rockery

and the last of the magnolias in profusion (I realise I haven't bored you with the magical glade in Kew Gardens yet).

In 24 hours we found ourselves in front of another fine church facade, this time that of the Duomo in Sarzana, quickly reached from Pisa Airport en route to Lerici and Tellaro on the Ligurian coast. But that chronicle is for another day.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)