Showing posts with label Europe House. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Europe House. Show all posts

Tuesday, 23 April 2019

Bonnard and Ruskin: diamonds and gemstones

From the big picture

to the cabinet of curiosities

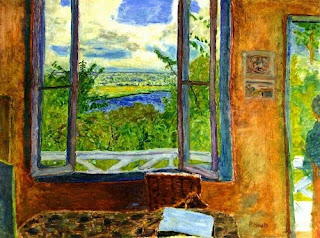

I feel enriched by two very different exhibitions. Astonished by so much critical negativity surrounding the huge Pierre Bonnard show at Tate Modern; all artists I know, including my beloved friend Ruth Addinall with whom I went, have nothing but praise for the master. What are the claims? He didn't reflect the upheavals of his times; he couldn't paint animals; it's only about colour. Stuff and nonsense. In the first case, just focus on what he did cover - mostly his various homes and women he knew well - and ask if he succeeded. My answer would be, more than I could have imagined before I visited. To catch the 'thing in itself'ness of people and animals does not require literal forms - these are forms in motion. And it's not just about colour; the ability to see different angles of a scene and to give them depth, even (this surprised me) profundity remains consistent in his work from 1907 up to his death in 1947. I loved all the works on display to varying degrees, with the exception of a few in the last room. And the very first of his Vernon rooms-and-landscapes from 1914 is a stunner, complete with dachshund.

The one so many of us know and love is from 1925, the dining room at Vernon with the dog's snout and brow just peeking above the table.

Maybe Bonnard was a god of small things, but to see into their essence is the task of genius. It helps that all these things I love so much. An airy room with pictures, a dog, a view onto nature. Coffee, too.

His nudes are intimate studies of his beloved Marthe, long-term companion, whose death in 1942 seems to have taken a lot of the elan out of his work. Again, Marthe in the bath is seen from so many different angles and there's a depth to this. Both these paintings are from 1925, but there are others just as fine from 1914 and the early 1940s.

Not a very kind segue, perhaps, to nutty John Ruskin and his horrified reaction to his wife's pubic hair on their wedding night. While Bonnard must have been genial company, Ruskin would probably irritate the hell out of you if you met him, with his ridiculous prejudices against the Renaissance, Die Meistersinger and Palladio, to name but three. But what he did cultivate in art and nature he pursued very beautifully with word and brushstroke, and the selective but rich exhibition at Two Temple Place, sadly now over, was such a joy. As is the building itself, an extraordinary late Victorian mansion commissioned by William Waldorf Astor in high neo-Gothic style which, of course, houses Ruskin rather well.

Downstairs in the exhibition, the looks were more sideways to influences than concentrated on Ruskin himself. But ascending the remarkable staircase - worth a visit in itself; it's all free - you hit two essential rooms. One is a recreation in homage to the museum Ruskin assembled in Walkley north of Sheffield, for the education of 'workers in iron' and other, concentrating on the natural history of the area. Sadly the original museum is no more, but it's been lovingly recreated in Sheffield, I believe, and this room, with the beguiling collection of minerals at its centre, was one big delight of the museum.

Then the pièce de résistance, space-wise. is the Great Hall with its Clayton and Bell windows of Swiss and Italian landscapes.

Here were lodged most of Ruskin's finest natural drawings featured in the exhibition, from the rocks of Chamonix to birds placed among representations by others (Audubon included)

including an exquisite representation of a peacock's breast feather.

So, what's this?

It's an EU-owl - the pun only works in German (EU-le). You might recognise it as the work of Axel 'The Gruffalo' Scheffler. He and other leading illustrators of children's books including Quentin Blake and Judith Kerr have responded, in the words of the blurb for the 12 Star Gallery's exhibition Drawing Europe Together, 'to make illustrated comments on the historical and possible future relationships between the countries of Europe, many of which are extremely touching and heartfelt.' Believe me, they are. And there was such a poignancy about the launch, for this was officially the last show in the 12 Star. Here's the artist speaking (I must get together more about the event, once I get hold of a copy of the book that accompanies it).

BUT. Not only are we not out, but one regional gallery decided the work was 'too political', so it got an extended lease of life. And now another, until 10 May, after Europe Day when we will be celebrating with the annual concert - here's a report of what we thought might be the last in 2018 - in St John's Smith Square (lined up whether we left on 29 March or not).

And meanwhile, here we are. Where exactly, philosophically speaking, is not clear, but still in the EU...

Sunday, 24 September 2017

Baltic island magic

It's there in this little philosophical gem, on a par with Tove Jansson's The Summer Book

and the singers, dancers and musicians of Estonia's Kihnu island brought it with them, along with smiles, laughs and a general happiness you can't fake, to the 12 Star Gallery of Europe House the other week (photos by Jamie Smith).

More on Mare and friends anon. In the meantime, I'm so glad I came across the American edition of Swedish entomologist Fredrik Sjöberg's The Fly Trap while browsing in Kensington Books (the author pictured below). A specialist in hoverflies, this splendid writer, translated with obvious style by Thomas Teal, has a rondo theme: 'the art and sometimes the bliss of limitation,' living as he does - or did, at the time of writing in 2014 - on Runmarö, a Swedish island of 300 inhabitants, much augmented by summer visitors. Here's the gist of it:

For an entomologist, 15 square kilometres is a whole world, a planet of its own. Not like a fairy tale you read to the kids again and again until they know it by heart. Not like a universe or a microcosm, similes I'm not willing to accept, but like a planet, neither more nor less - but with many white patches. Even if I were to swing my net an entire summer without adding a single species to my collection, the gaps in our knowledge will still be great, if not quite immeasurable. The fact is, they keep growing, keeping pace with our knowledge.

The issue, reduced to Strindberg's dismissive term 'buttonology,' connects with a parallel interest in the geologist's 'feeling for time' and Sjöberg's own attempt to 'grasp...temporal spaces so great they border on eternity' (Chapter 15. 'The Legible Landscape', is a masterpiece of writing about what we can grasp and where we stop).

Yet the perceptions are not random, despite the fluidity of Sjöberg's ruminations, often tinged by wryness; and there's a parallel character study, of the marvellous man who invented the giant fly trap of the title (and pictured above), René Malaise, a Swede (despite his French name) born in Stockholm in 1892. What a life! Malaise might have limited himself to one area of expertise, study of the sawfly, but like Sjöberg he had interests elsewhere, too - there's a fascinating final chapter on his collection of grand masters - and he travelled. A lot. In 1920 he left Sweden with five other adventurous folk, four men and two women in total, to explore the remote Kamchatka peninsula. Sjöberg's news that the collection from a later expedition to Burma was lodged in Gothenburg's Museum of World Culture - here's a specimen -

gave me a special quest when I was there the other week for Santtu-Matias Rouvali's first concert as the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra's principal conductor. The helpful folk on the desk couldn't locate it, but there was a screening downstairs of photos from the Kamchatka adventure, one of three selected Swedish explorations.

A shot of Malaise himself came up on the screen, so I presume the Museum is happy for me to use the original online.

He took some splendid photos, like this one (though it may well be in Japan, which he visited after Kamchatka, and where he experienced a devastating earthquake).

And here's company, though I have no idea why the woman's face is scratched out.

One more in the context of the big room downstairs at the Museum

and a crate for the sort of thing I was actually hoping to see tucked away in the corner.

It's a very splendid building with a cafe on a kind of mezzanine level

which extends on to a terrace.

The exhibitions are there mostly to make schoolchildren think of the world around us. I loved the forthrightness of the display panels (in Swedish and English) in the way they described the plunder of the earth and the quashing of human rights. Like this: 'One could use many grave words to describe how a small percentage of the world's richest population have exploited the world around them in the past hundred years: irresponsibility, arrogance, greed and egoism'. I half expected an added 'so f*** you, 45th!' We could afford to be more direct in our language here. The fourth floor exhibition included a refugee boat whose occupiers had all drowned

and this cabinet of items owned by Mexicans and south Americans trying to cross the border to the north, with information about some miserable fates.

Which leads us back to the colourful woven dresses of the Kihnu islanders, living under happier circumstances and one of the most enlightened governments in the world. I first wrote about them describing our unforgettable day trip from Pärnu last summer, and I've managed to cut down for accommodation here one of the putatively 2000 year old wedding songs still in their repertoire, which they performed for us in a room of the island's museum.

It was so good to see once more Mare Mätas, the Tallinn-trained lawyer who'd returned to her native island to foster its UNESCO-protected culture, and the sweet accordion-playing girl who's won all sorts of awards in music competitions and has grown up quite a bit since then (she must be 11 now). There she is on the left.

This time it wasn't just dancing ladies. The most jovial chap imaginable sang ballads to his accordion in a very splendid and idiomatic style, and his son came along too. They're demonstrating their splendid traditionally-designed and knitted jumpers, two months in the making, for Mare here. I want one (jumper).

This was the other book-end reception of an exhibition of really superb Kihnu-people photos by the Frenchman Jérémie Jung, some of which formed a good backdrop to the performances. Clearly they loved him there, from their genuinely warm words about him, and when it came to joining in the dances, he knew all the steps (not featured here, but there was audience participation later).

I do hope there's funding for a book of the pictures. And still, deep in my soul, there's the wish to spend a whole year on the island to see nature through all its seasons. No reason that shouldn't happen some time, if not for a while yet.

Wednesday, 15 December 2010

Turkish family heartbreak

Die Fremde by Feo Aladag, the winner of the European Parliament's 2010 Lux Prize, will be hitting the screens here some time next year as When We Leave. A lucky few had a chance to see it on Monday evening as part of the new Europe House's minifestival.

It's a masterpiece. The story, you might have thought, would have been told before: a Turkish woman leaves her abusive husband in Istanbul and travels with her young son back to her family in Berlin, only to face the immutable codes of tradition and community which cast such a pall even on a seemingly ordinary and recognisable home life. All this is done with such painful sensitivity and in performances of often restrained realism. The cinematography captures the inner lives of the characters in mundane surroundings, especially during the blue light of the hour of the wolf and the dawn, celebrating the everyday without a false note.

Which is why the inexorable logic with which all too familiar family disputes unfold into tragedy is the more shocking. You could hear the incredulous gasps of the comfortable European audience at the entrenched attitudes which would separate mother and child, but you come to understand, if not entirely to sympathise, with the motivations of the protagonist's humiliated father and fearful mother.

As this isn't yet released here - though already available on a German DVD with English subtitles - I won't say more about the plot except to note that the beautiful, dignified actress in the central role, Sibel Kekilli (pictured above), deserves every accolade. Watch the trailer (German subtitles only) below. You'll need to go fullscreen over on YouTube by clicking on the picture once it's started.

Diplomacy requested the removal of a central tranche here about the obscene adversaries of Europe House and their terrorist proposals (as well as the comments). So let's move on and wash away the unpleasant taste with a glimpse of the far from over-lavish reception for Maggi Hambling last Tuesday (all the following photos taken for the European Commission).

Maggi made a great speech, of course, though sadly I couldn't hang around beyond that because I had a class to teach. Here is the redoubtable lady by her biggest wave

a few smaller ones

and the resplendent Andrew Logan, whose cufflinks I wear with pride.

And so it continues. I missed the jazz concert last night, but I hope to be there for a discussion about Pinter in translation tomorrow. This in fact all came about because J asked the great man shortly before his death whether he thought the taciturn, long-pausing Finns would have a concept of what was Pinteresque. To which came the immortal reply 'fuck Pinteresque!' As Harold Pinter once said...

Labels:

Die Fremde,

Europe House,

Feo Aladag,

Maggi Hambling,

Pinter,

When We Leave

Tuesday, 7 December 2010

Making waves for Europe

The adorable Maggi Hambling, who has become our Newest Best Friend since her partner Tory Lawrence - also a remarkable artist - had an exhibition in the 12-Star Gallery, launches what promise to be ten days of enlightening events at the new Europe House in Smith Square. This seemingly shameless piece of diplo-mate promotion (goddamit, it's my blog, I can write what I want) comes about because I Believe in European Culture to connect us as much as he does, and because it's about as good an arts spectrum for a minifestival as it gets.

There should be something to please everyone. Quite a start to have one of Britain's leading artists kicking off with a sequence of North Sea pictures. Tomorrow there's a free screening of archive European films showing a vanished world from 1909-21 (I've seen the DVD, I know how extraordinary it all is).

Plus, inter alia, major poets, a Proust round table and another free musikfest with the vivacious London Bulgarian Choir and others...all details here.

It's been a productive year for Maggi, with earlier exhibitions at the Fitzwilliam and the Freud Museum (that one's still running, I believe) and the launch of a book about her magnificent Aldeburgh scallop.

We're waiting to receive our copy as a present from another friend who bought it at the launch and is coming to the Exotic Europe event, but of course I know and love the object itself.

I popped over on my bike to south London in September to pick up the birthday present I'd bought for J - one of Maggi's Oscar lithographs - and was regaled with a glass of whisky and tales of her and Tory's recent trip to Moscow. Hence the hat.

As I was leaving, Maggi pressed on me a bag of apples, given to her by a taxidriver on the way back to Sheremetovo Airport. They'd come from his maminka's dacha apple-tree (I see I'm repeating myself a bit, but only in part). I managed to cycle back safely with the framed picture in my pannier, but just as I was rounding the home strait, the pannier came off and the apples spilled all over the road. One kind neighbour who stopped to help me pick them up was impressed to be rewarded with a handful for her pains. Another became a provisional christening present for baby Mirabel (hurrah, We Are a Godparent again), who was probably happier with this shiny round rednyellow yabloko than a silver spoon.

A neat parable of the joy (if that's the right word, considering the fierce aspects of the senior and junior artists) of giving and receiving, I reckon, if that doesn't sound too seasonally pious.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)