Where, oh where - paraphrasing/adapting Pushkin's and Tchaikovsky's Lensky - have you gone, golden October days? Every Sunday in that month was one of brilliant sunshine, whether in Sandwich, Oxford, Athens or Samos. It hardly seems less than four weeks ago that we were hiking the hills of that wonderful Greek island, discovering fruit bursting and dropping ungathered from the trees. And there I was, today, one low ebb of the year - though I'm tolerably jolly in myself - hanging around on freezing outlying Piccadilly and Bakerloo line stations waiting to go and get a verdict on the fracture from the maxillary department at Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow (the second picture, obviously). Not at all grim inside, in fact, as NHS hospitals go. I'm getting to compare them all these days, split as I have been between six of them.

It cast me back to a bleak January day in Edinburgh in 1984 when I took a journey through the snows from our mice-ridden Dalry Cemetery Gatehouse to Portobello Cat and Dog Home, hoping to lay my hands on a mouser only - very reasonably - to be told that the carers didn't like to let cats loose with students who might desert them or, at best, shunt them around (eventually we got Sinope/Snoopy on loan from Iqbal and Sharif over the road).

Not to detain you with the boring details of this morning, but I must side- or even up-grade the 'supraorbital' wound to a fracture of the left sinus wall. Whether it needs to be operated on will depend on the CT scan which should reveal how far back the damage goes. Ho hum: only another fortnight's wait, with the comforting intelligence that if I start bleeding or vomiting again, I must take me back to A&E immediately (unlikely, insha'Allah).

In the meanwhile, preferring to turn the calendar back a month as November comes to a close rather than forward to Christmas as everyone seems so hell-bent on doing, I think of our Samian time, not all blessed with clear blue skies but all of them fresh and bracing. We harvested a good crop of local produce to keep us going in our Potami retreat.

The day of our fruit walk saw a rather bigger detour than we'd intended around mountain villages through valleys of silvers, greens, reds and greys

and eventually down to the coast path between Megalo and Mikro Seitani beaches, which we'd explore the following day after the storm had passed.

Even the coldest day of the week, when we froze above Manolates, was rather beautiful, with the Turkish coast at its clearest in the sun while we shivered under a grey pall.

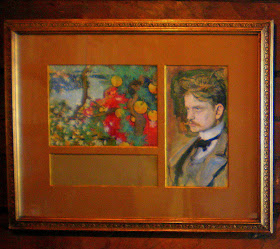

The pomegranate up top, of course, plays a key part in the Persephone myth of the seasons. I'm just in the mood for the restrained emotions of Stravinsky's melodrama, the highlights of its Hades scene including the quietly ravishing 'Lullaby for Vera' to be heard here in Sir Andrew Davis's Proms performance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Paul Groves and Nicole Tibbels. Forgive the artwork; it's beyond my control.