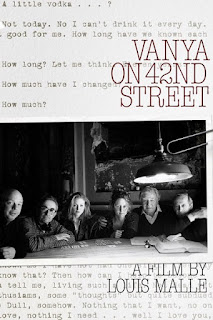

A second viewing of Vanya on 42nd Street after a couple of decades - I finally got hold of the Criterion edition - persuaded me that it must be. And when I discussed the film with Matt Wolf, theatre doyen of The Arts Desk and the International New York Times, at the Hospital Club 100 Awards the other week - more on those, and TAD's part in them, anon - he said it was one of his desert island films. Mine too, maybe even in the top three.

Criterion's accompanying documentary sheds further light on why this was an unrepeatable beacon in the history of theatrical performance even before Malle appeared on the scene. The enigmatic and fascinating, sometimes maddening Andre Gregory hadn't directed a play for 14 years when he first gathered together a group of America's best actors, trained in the Stanislavsky tradition, to meet and work on the multiple possible meanings of Chekhov's towering masterpiece without an end in mind. In 1991 they started to perform it to audiences of 20 to 30 people a night - I think if I could choose one trip back in recent time, it would be to have joined those very distinguished who's-who-of-culture folk. The performances came to a halt with the death of Ruth Nelson, playing Nyanya Marina. Wallace Shawn persuaded Gregory to pick it up again after a year, and the replacement was a former colleague of Nelson in the Stanislavsky-based group theatre, the luminous Phoebe Brand (pictured here in what turns out to be the opening scene of the play, with Larry Pine as Astrov and Wallace Shawn as Vanya).

They played it again, at a table with the invitees sitting onstage too and moved, like a camera angle, from place to place, in the decayed Times Square Victory Theatre, a former movie palace, and then moved over to the splendid ruin that was New Amsterdam Theatre, stinking of rat piss and mildew, when Gregory invited Malle to change the perspectives and film the venture as a farewell.

Even on a second viewing, the point at which the carefully set-up arrival of the actors - already subtly allied with the roles they're going to play - and the tiny invited audience - including Madhur Jaffrey, playing a role too - glides into the opening of the play is startling. David Mamet's adaptation, from a literal translation, plays its part in that, treading an exquisite line between the essence of Chekhov's dialogue - which helps, because it's usually so direct - and colloquial, but never coarse, American vernacular. I ordered up the script, and it wasn't easy to find: odd, because this is the best version I know. The tree-planting Dr Astrov's first big speech always has extra potency today, but never more so than here:

Burn peat in your stoves..build your barn of stones. You understand? Yes, sometimes we cut wood out of necessity, but why be wanton? Our forests fall before the axe. Billions of trees. All perishing. The homes of birds and beasts being laid waste. The level of the rivers falls, and they dry up. And sublime landscapes disappear, never to return, because man hasn't the sense enough to bend down and pick up fuel from the ground. (To Yelena Andreyevna:) Isn't this so? What must man be, to destroy what he never can create? God's given man reason and power of thought, so that he may improve his lot. What have we used these powers for but waste? We have destroyed the forest, our rivers run dry, our wildlife is all but extinct, our climate ruined, and every day, every day, wherever one looks, our life is more hideous. (To Ivan Petrovich:) I see, you think me amusing. these seem to you the thoughts of some poor eccentric. Perhaps, perhaps it's naive too on my part. Perhaps you think that, but I pass by the woods I've saved from the axe. I hear the forest sighing...I planted that forest. And I think: perhaps things may be in our power. You understand? Perhaps the climate itself is in our control. Why not? And if, in one thousand years, man is happy, I will have played a part in that happiness. A small part. I plant a birch tree. I watch it take root, it grows, it sways in the wind...And, of course, it's possible that I am just deluded.

Of course, despite this, the interior monologues and Sonya's great final speech which Rachmaninov set to music, nothing is terra firma in Chekhov. The characters shift, become sympathetic and unsympathetic, surprise us with the ferocity beneath an apparent apathy or the aimlessness between seeming vitality. And this film, this production, convince me that it really does take years, months, for actors to be those characters. The ensemble is perfect. Wallace Shawn, the maverick previously caught in Malle's My Dinner with Andre, is the most unpredictable of all: you have to pinch yourself to realise he's not being but acting (what's the difference in this set-up?) While Julianne Moore is indeed ravishingly beautiful, she can slip from radiance to just-reined-in hysterical misery in a moment. Your heart aches for Brooke Smith's Sonya/Sophia (pictured below with Moore, Shawn and George Gaynes as the pompous Professor). I don't think I'll ever hear her 'we shall rest' epilogue more magically spoken.

What's truth here? As in Tolstoy, whatever the character feels at any given moment - unless he or she is self-deceiving. Two telling sentences from Gregory, who grew up in America to Russian parents, provides another clue to the wonder here: 'Russians go from manic to depressive in a second. Often when Chekhov is played, the actors stay with one emotion for too long.' It reminds me of what Tim Carroll said about being authentic in every moment and not settling for an overall mood - a mistake all too easy to make in relation to the exit of Malvolio in Twelfth Night. Carroll's magical all-male production at Shakespeare's Globe, another production which must rank among a different top five - best in theatre - didn't make that mistake either.

That may be what makes Noah Baumbach's Margot at the Wedding tick, too. Its adults are deeply f*****-up and intermittently vile to each other, and if their children aren't the same, they will be, given parents like these. And yet, they're all human and there's real love in there. Again, the ensemble is compelling; it's so good to see Nicole Kidman as a volatile narcissist (pictured above with Zane Pais as her son Claude), a real character rather than the period-costume waxwork she's too often asked to be, and Jennifer Jason Leigh (below right) mostly still rather than mannered and twitchy as Margot's sister, and the big laughs come from Jack Black as the Leigh character's unsuitable-but-really-quite-bright-until-he-goes-beyond-the-pale future husband.

In looking for pictures I did a double take when I came across one where Nicole's character gets stuck up a tree and the caption above reads 'The Hunt for the Worst Movie of All Time'. But I enjoyed reading the reasoning behind that - a rant against the obsession with bourgeois angsts - and you might too, but don't let it put you off a rare glimpse of life as some of us know it. The Squid and the Whale, Margot's predecessor, is likewise superbly cast, and runs along similar lines about parental irresponsibility. Henry James might have approved of both, if slightly startled by the preoccupation with young-adolescent sexuality.

No comments:

Post a Comment