I knew cellist Alban Gerhardt (pictured above with feline companion by my good friend and best photographer of artists in the business Kaupo Kikkas) was the sort of Mensch who would respond to my plea for an Arts Desk 'First Person' piece on why Germany was wrong to send its cultural scene into a second lockdown and - by implication - why that mustn't happen here (though from what I can make out of the latest proclamation, finally given as I prepare to publish this, it will, from Thursday).

All of us lucky enough to attend live concerts in England over the last few months - poor Scotland never got the green light - will testify as to how responsible and orderly they've been: temperature testing and handwash plus registration at the door, ushering to specially distanced seating, masks on in the hall (the artists wear them on to the platform but remove them after reaching their equally clearly-delineated places) and an equally careful exit routine (no lingering in groups to chat). The only thing I can add to everything that Alban has expressed so succinctly is that, in addition to the uneven application of rules to pubs and restaurants, the spreading-ground of schools has been overlooked, too; if only there had been proper guidelines there.

Also have to own up to the special privilege of being among the lucky few at events not officially open to the public at the Royal Festival Hall and LSO St Luke's (the tiny numbers also very carefully calibrated, the ritual of admittance and departure even more regimented). I wonder if even the filmed, livestreamed events planned will bite the dust. They're not the same, of course - you can tell the players, singers and conductors need a real audience input, though Julia Bullock was so communicative on Thursday (the hall from my seat above, Bullock pictured by Mark Allan below) - but still very welcome and will be even more precious if we're not admitted any more).

The riches between July and now have been unprecedented, starting with the brilliance of Raffaello Morales' Fidelio Orchestra Cafe recitals. What a great moment that was when Steven Isserlis stepped out in front of a public, albeit a very small one (25 people) for the first time in four months which must have felt like half a lifetime. The moment is so well captured in Nick Rutter's photograph.

FOC has been going from strength to strength, though Angela Hewitt's appearance this coming week couldn't happen owing to travel restrictions - heavenly Imogen Cooper is due to take her place. She will only do so on Tuesday and Wednesday, and then of course nothing for at least a month.

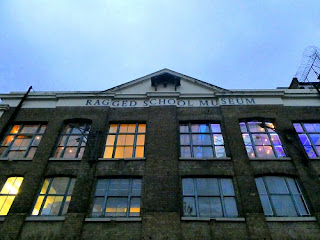

I have enough recent memories to last a lifetime, above all of the two little-great not-so-mini festivals pioneered by Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy at the Ragged School Museum (a poleaxing sequence of masterpieces in devastating performances) and by Jonathan Bloxham's Northern Chords Festival in Newcastle last weekend. These are the truly heroic musical figures of the year, along with the Wigmore Hall's John Gilhooly. To keep the memory of the Newcastle idyll going, next stop on here will be a photojournal ot autumn light on that memorable Sunday. May the inner light continue, too. We all need it.

Footnote: Raffaello (pictured above sitting on the stairs leading to the balcony part of the cafe) got in touch last night to tell me about the situation with the 'Imo' concerts this coming week (two remain, last one on Wednesday evening). His additional positivity needs to end this piece: 'Life goes on and we are more combative than ever. I think the best reaction we can have at this point is being constructive and showing how fundamental our contribution is. The narrative has to change from one of lamenting our condition of perpetually under-considered category to one that proudly shows how relevant and necessary we are to civilzation...one of those tasks that we'd better get going at soon'. Hear, hear.