I thought I must have seen Frank Ripploh's Taxi Zum Kloh during my closeted but curious student days in the early 1980s, so talked about was it at the time. But if I had, I would have remembered at least the scenes which made it notorious then and which still had us sometimes squirming and looking away last night*: non-simulated sex which makes the grubby rendezvous of Mark Rylance and Kerry Fox in Patrice Chéreau's Intimacy - and what a surprise we got stumbling into that one out of the heat of a Paris July - seem tame, a shock through a lavatory glory-hole (I'm too prudish online to show you what happens next below, as our hero sits on the bog casually marking school work),

a golden shower, a graphic clinical inspection for STD and a surprising take on child abuse. That last is thankfully moral: two of the gay characters waspishly comment on what would seem to be a genuine German film-warning to children to beware paedophiles with the same repugnance we feel, while Frank fends off an over-frisky pupil who's there for home tuition in the kitchen.

None of the extremes, the censors decided at the time, could be thought of as pornographic because all support, if sometimes contradict, the tender love story at the heart of the film.

There are no drums and trumpets for any of the things that just happen to the characters, as they do in life (Ripploh, playing himself, claimed that most of the incidents were autobiographical). Still surprising is how natural and funny it remains as an, ahem, warts and all picture of one type of gay life - or maybe two running parallel - lacking the gym-worked bodies and soft centres of later movies as director, writer and protagonist Ripploh tells us how it was for him in 1980s Berlin.

The anti-hero is a good teacher and the classroom scenes delight through the smart responses of the kids. One wonders how much they were told about the film they were in. But then this was West Berlin in the early 1980s, where, we're told, everyone took such things in their remarkably tolerant stride.

Frank is unapologetically promiscuous, and frankly the kind of shit who wouldn't have hesitated to pass on a deadlier virus in the AIDS era then to come (hospitalised for six weeks, he's off to the nearest Herren Klo, which of course is men's toilet, at the first opportunity). His lover Bernd is sweet, homeloving, dreams of a retreat to a farm; it ain't going to work. Or is it? I said to J halfway through, 'I'm going to love this film if no-one has to die at the end'**. So I love this film.

It was a huge hit in the astonishingly direct-speaking Germany of the period. Heterosexuals went in droves to see what the gay life might be like. Sympathetic as the UK censor seems to have been in 1981, there was no way he could give any kind of certificate to the more outlandish scenes. The director of London's ICA at the time agreed with him that cutting would deprive the film of its balance, and ran it under film-club conditions with black pen scrawled over one sequence which could have been against the law.

Police and councillors up in Edinburgh threatened to seize the reels and destroy them. As the print happened to be the only one with English subtitles, done at the cost of thousands, each reel was bagged the minute it finished, plonked into a car at the back door of the cinema and driven off to a secret Morningside address. The threatened impounding, in any case, failed to happen, though a wild party to celebrate resulted in several arrests.

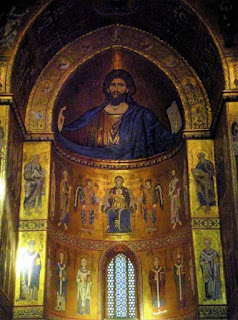

Success seems to have gone to Ripploh's head. That made his mentor Rosa von Praunheim, pictured above in 2008, very sad. Von Praunheim and other friends who remember Ripploh in an accompanying documentary on the DVD testify to a man who was funny, spontaneous and enthusiastic, but fundamentally as unreliable as his screen self. The next couple of films were by all accounts (and to judge from the handful of clips shown) absolutely terrible. But as von Praunheim records without rancour, Taxi Zum Klo remains infinitely more popular than any of his own more earnest this-is-what-it's-like-to-be-gay-in-today's-society homilies.

Ripploh died of cancer in 2002 at the age of 52 , but his masterpiece lives on with a vitality missing in all gay-themed movies I've seen of late (anything by Ferzan Özpetek before the recent disappointment of Magnifica presenza, in which the gay element is in any case a given, honorourably excepted). On Pride Day, when it turns out that there's still more to fight for than we thought ten years ago and much of the bigotry which had gone underground has now popped up, especially in France, to try and beat up the marriage issue, we need a film as insouciant and in-your-face as this more than ever. And who's making them now? German trailer follows.

*The evening had begun with an attempt to watch Written on Skin again, this time as televised on BBC Four, and maybe write about it for The Arts Desk. But only minutes in, I confirmed my existing opinion by finding it every bit as frigid and pointless, magnificent performances notwithstanding, as I had when I went to see it at the Royal Opera. So there was nothing more to say, and I switched off after 20 minutes. All the human interest missing therein was to be found abundantly in Taxi Zum Klo.

**At least in Behind the Candelabra it isn't the victim who dies. I enjoyed its quiet coda as well, of course, as impeccable performances by Matt Damon, Michael Douglas and Rob Lowe.