An impressionistic outlet for some of those thoughts, musical and otherwise, I don't have a chance to air in the media

Tuesday, 29 January 2019

Johnson and Carduccis play Johnson

As in our national treasure clarinettist Emma Johnson (pictured right) and the Carducci Quartet (above, Matthew Denton, Eoin Schmidt-Martin, Michelle Fleming and Emma Denton) giving the world premiere last Thursday of Angel's Arc by my very good friend Stephen (no relation to Emma). This was his second big event at the Cadogan Hall; back in 2016 his orchestral homage to Bulgakov's cat-demon, Behemoth Dances, was performed here by the Moscow State Symphony Orchestra and Pavel Kogan following its Russian first performance. I couldn't make it, but I've since heard a recording.

Apart from its strange and reflective inner core, Behemoth Dances couldn't be more different from the quintet for clarinet and strings. Obviously the forces make a difference, but this is somehow more personal, Stephen reflecting back on his troubled teens from the perspective of a more recent grief . Placed after Brahms's Clarinet Quintet and an interval, and before Mozart's great example, it had a different dynamic, the clarinet more apart and clearly leading in a very vocal way (how many other composers today make the instrument sing like the human voice? I'd love to hear a soprano or tenor-and-string-quartet work from SJ) To me the strings were more bent on effects to create atmosphere, though there's a lively central section with a riff passed around the players - Behemoth inside out - which Stephen calls 'a nocturnal scherzo, whose sweet-sour alternations recall the moods (and some of the colours) of Mahler's haunted symphonic scherzos'; what came to my mind was more the extraordinary boogie-woogie-plus-tappings core of Shostakovich's Thirteenth Quartet.

But I don't want to do the usual critical thing of citing influences, other than those Stephen intended; I certainly caught a paraphrase of several bars from the Andante con malinconia of Walton's First Symphony, which he did mention in the note (and we both know a bit about malinconia). I was so proud of my perceptive artist companion, Pia Östlund, who 'got' and encapsulated the bigger picture much better than I did, and with little knowledge of the background; she described it as personal and introspective, but at the same time so spacious. We both agreed that the ending was pure metaphysical poetry. Stephen hoped it would convey gratitude as well as grief, and it does. I'm sure he couldn't have wished for a better performance, and the players were all so subtly fused in the Brahms and Mozart (loved the little transcription of Mozart's 'Ave verum corpus' as the encore, too).

Without being told I wouldn't have got the hidden reference which connects to Behemoth Dances through cats: in this case the most undemonic and human cat I've ever met, the late Agatha (I always called her A-GAAA-ta as in the Freischütz heroine), one of the few who could turn my dog-loving head. Expanding on his original programme note in a blog guestpost for Jessica Duchen, Stephen noted how Agatha's death triggered off recent griefs for his splendid father-in-law Canon Harold Jones and his aunt, Elizabeth Johnson. 'Playing around on the piano it struck me that I could make a kind of Schumann/Shostakovich-style cipher out of the letters of Agatha's name: with Te (sol fa) representing B, plus H from German notation, it gave A-G-A-B-B-A - a chant-like motif very like the haunting plainsong phrase "Lux aeterna" I'd used in Behemoth Dances.' Agatha, you will never be forgotten (cue repeat pic above).

Quality time with Agatha staying at the Johnson-Jones residence in Sutton St Nicholas was interspersed with hearty walks. And this connects very much with the new work, because Angelzarke on the West Pennine Moors was a favourite walking and cycling haunt of the young Johnson. Now he walks with greater peace of mind, for the most part, with Kate at his side. Another personal shot, then, from a May 2011 (!) ramble we took with the JJs up and around and down Skirrid Fawr.

I have to evoke those bluebells seen from the lower slopes again, because they offer promise of the spring which seems so far away still.

Even so, the snowdrops were out in force around some of the Brompton Cemetery graves as I cycled to yet another appointment at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital yesterday - as far as I'm prepared to go on a bike at the moment -

and someone had thoughtfully placed a bunch of daffs through the arm of a stone angel.

Praying I'll have had my op - still not scheduled - and be free of the stent when spring does arrive, so I can walk much further than I do now.

Tuesday, 22 January 2019

Hospital reading

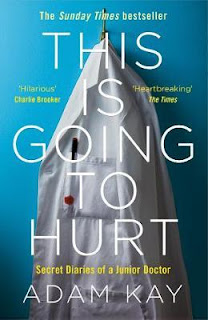

Not reading in hospital - that covered three and a half books by Elena Ferrante - but reading about a phantasmagorical version

and the blackly comic reality.

At the start of both, which I read more or less simultaneously, I'd have been inclined to give the palm to Gwyneth Lewis's A Hospital Odyssey, a homage to Homer about the fantastical journey undergone by the devoted wife of a cancer patient - yes, I know it sounds unpromising, but it is unremittingly brilliant, playful and learnedly witty. After all, isn't Adam Kay's This is Going to Hurt a bestseller, an easy read - at least in the pageturning sense? Well, the more people it reaches the better. It has the advantage of on-the-spot reporting by a junior doctor in the shape of a series of diaries; however polished up for the book, they have the ring of total truth, and the abiding impression I get is that no horror story or horror film can be worse than the capacity of the human body for turning against itself.

Kay is infallibly, laugh-out loud funny; I wouldn't know what to quote to you since the choice is infinite. But he has a serious message about the overworked, underpaid and undervalued workers of the NHS, while constantly stressing his awareness of the value of his life-saving work to himself and to others. What makes one angry is that here, as in so many jobs but more so given the life-or-death hazards the operative doctor undertakes, there's so little thanks that the doctor is painfully grateful for any kind word. It's terrifying that there's no emotional or psychological support for the many stresses. And of course the final fury is reserved for Jeremy Hunt and the politicians who have NO IDEA what these real-life saints undergo. Get it, go see Kay's one-man show on the subject and/or wait for the TV series.

My thanks to my best pal on The Arts Desk, Graham Rickson, for sending me a copy. And to the London Review of Books Bookshop, to the cafe of which I and some of the students now retire after my Monday afternoon Opera in Depth classes at Pushkin House, for having A Hospital Odyssey on recommended display. Gwyneth Lewis's Sunbathing in the Rain: A Cheerful Book about Depression was the most insightful and also the most prose-poetic book I read in my darkest hours, so I knew the writing would be good, though I hadn't sampled her primary talent as a great poet.

Which she undoubtedly is: what seems to flow so easily as Maris undergoes, Odysseus like, a number of bizarre, shape-shifting trials in search of a stem cell for her dying husband must have been the work of years. I love the authorial voice which speaks to us so directly (UPDATE: though separate from the heroine, she - ie the author - turns out to have undergone the same reaction to her husband's hospitalisation and near-death, hence the sense of total identification with a 'real' subject undergoing a fantastical metaphorical journey. I found out something about this in Lewis's blog attached to what must have been a rather odd radio drama, at a mere 45 minutes). This may seem almost sentimental, but within the tough, chameleonic context it's superb. Maris sees a robot 'sommelier' sampling phials of blood and sees one with the name of her beloved Hardy:

....It was ruby red,

an impossible scarlet that caused her alarm

the moment she saw it. Sick with dread,

she watched the gourmet as it tasted,

swilled the wine round its specialist mouth

then spat out the taste of her husband's health.

It hummed and ha'd, its innards whirred

and said it tasted 'a soupçon of anemia'

then worse. It printed the verdict: CANCER.

Maris was stunned. This was a story

that happened to others, not to Hardy and her.

Then she was pierced through with pity

for him, brave man, who'd hidden his terror

of this, the most feared saboteur

of all. Stop reading. If your partner's near

I want you to put this poem down,

surprise them at the morning paper.

Nuzzle their neck. When they ask, 'What's wrong?'

say, 'Nothing,' but hold them close, while you can.

Maris's adventures, accompanied by the dog Wilson and shape-changing Ichabod, include meetings with Philoctetes of the noisome wound, a microbes' ball (appealing to my own febrile imagination as one horrified by the low level of hospital hygiene), a spider Penelope, the Cancer Mother with her dragon son, something equating to Helen of Troy at the bottom of the sea and Aneurin Bevin as well as Hippocrates on the Island of the Blessed. Sounds intriguing? It would to me as a prospective reader, though my bait was the trustworthiness of a writer I already knew and loved. I can't recommend this mock-epic too strongly, and I know I'll read it again soon.

Meanwhile, how am I? Angry that I still don't have a date for the stonebreaking operation, despite the consultant saying emphatically that I needed to have one exactly a week ago. Time to get on the blower to Urology at C&W. In the meantime, the stent means I lead a half-life. I can't walk or cycle very far or go to the gym; the short distances I travel on foot or bike mean pain and blood. I know this is normal because the NHS kept me on hold for three months two years ago when I came back from Turkey, and the one-day two-in-one op, with the stent inside me, 'to be removed within two weeks' said the specialist, but I was told it was 'OK' for a good deal longer. Liveable with, yes, but not great. Well, there are people waiting for ops far more serious than mine. But I still have to be the squeaking gate...

UPDATE: I made the call. Five minutes through the automated hoops before I was put in the queue for urology appointments. 'We expect to answer your call in approximately two minutes.' Then 'we expect to answer your call in approximately one minute'. All against the same initially attractive but repetitively maddening Latin-American easy listening. For the next 24 minutes (do they make money out of this, like they do out of hospital car parking?) The live voice I finally got, not prone to making sympathetic noises about the wait (I was polite), put me through to her colleague who deals with appointments. An answerphone promising to call back if details were left. Which she did, to be fair, within the hour. I told her that Mr X promised that a date for the op must be arranged soonest a week ago. 'Well, it would have helped if we'd got the right paperwork from the junior doctors' So you haven't? 'Not yet. Mr X is currently on leave and I know he's already moved some January appointments from January to February. He's the only one doing this. But I'll let you know as soon as I have a date'. So it goes.

Sunday, 20 January 2019

Films before the fall

Or, to be precise, what we watched over the Christmas period before I was hospitalised: two outright masterpieces, two American indie slices of life (one admittedly very out of the ordinary). Netflix justifies its existence by funding the Mexican master Alfonso Cuarón's Roma. Cuarón had already carved his place in cinema history with the sexy-sad Y Tu Mamá También, but I'm sure he feels for a number of reasons that Roma is his magnum opus (by the way, though I couldn't care less about the Oscars, I think it's absurd that a film like this is shovelled into the 'Best in a foreign language' category when it's surely a winner on any level).

In it, he manages so many things, above all to turn the intensely felt experience of his childhood, with incidents carried over wholesale, into the most poetic movie-making, a perfect balance of subjective and objective, and to celebrate the hitherto unsung life of a native Mexican, the much-loved family maid Cleo, a Mixtec woman from the village of Tepelmeme in the state of Oaxaca: in real life it's Liboria Rodriguez, who has seen the film several times and always cries, but for the children, not for herself, and the actor is Yaliza Aparicio, who had no previous film or stage experience and who even featured on the cover of Mexican Vogue - a first, shamefully... Netflix released this lovely photo of 'Libo' and Cuarón as they are now.

How well we get to know the family home in the (then) shabby-genteel Roma district of Mexico City, with its garage runway, always covered in dog poo, ill negotiated by the fraught father and mother when they try and drive their cars up to the door. It soon emerges that all is not well between husband and wife.

How shocked we are by the student uprising which ended in slaughter, seen from the windows of a furniture department; this is a realisation of a newspaper clipping which the 10-year-old Cuarón saw, and had explained to him by his communist uncle. 'My little middle-class bubble burst,' he says. 'I realized there was a way bigger bubble, one that was more complex'.

Also compelling (though what isn't, in this film) are the scene showing the government's military training of young men in a very specific martial art - very expensive to film because the extras all had to be taught the discipline -

and by the heart-in-mouth single take where Cleo saves two of the children from drowning (young Alfonso was one of them, in reality).

I wouldn't have noticed had I not read an article in a film magazine while I was in hospital that the camera starts by looking downwards and that gradually more sky is introduced into the final scenes, looking upwards; but this, I'm sure, is something one registers unconsciously. There's so much detail in every frame, though, that I regretted not seeing Roma on a big screen, and look forward to correcting that.

Just as great an achievement, in its own oblique but often very funny way (yes, a German comedy, or rather tragicomedy), though the deliberately blanched cinematography is hard to adjust to, is Toni Erdmann, directed, written and co-produced by genius Maren Ade.

Now that Bergman is no longer with us, and Lars von Trier seems to have lost his way after his amazing earlier films - though I did like Melancholia, if 'like' is the right word, and I don't have the courage to see whether the sexually explicit and violent later works actually have a moral compass and a singular touch, as The Idiots ultimately did - Ade must take the palm for getting layered, complex performances out of two remarkable actors.

The title refers to the bewigged, false-teethed alter ego of sad clown Winifried (Peter Simonischek, whom I want to see in Shakespeare); but Sandra Hüller as his career-driven daughter Ines is just as compelling, and has a harder job winning our sympathy - though she does, in spades, and there's a sensational rendition of a Whitney Houston song which marks a turning-point in the film.

Even the outcome of the last scene is held in the balance, and the later stages are totally unpredictable. Let's just say that Toni/Winifried's last stunt, within the compass of the film, has to do with the costume in the poster.

What you get in two films about American life are a truthful performance from the luminous and versatile Saoirse Ronan in Ladybird, about a not-much-more-than-averagely-rebellious teenage girl slyly subverting what she can of small-town life

and slightly stylised, but nevertheless brilliant ones in a classy take on the true-life tragicomedy of a skating queen

from Margot Robbie (curiously turning up as Gloriana vs Saoirse's Stuart in what sounds like a turgidly-scripted Mary, Queen of Scots; surely Josie Rourke should have known to adapt Schiller's Mary Stuart rather than go for a stilted new screenplay) as well as an idol of mine, Alison Janney, who will forever be the surprisingly sexy, always sassy C. J. Cregg in The West Wing but excels here as the Mother from Hell,

and Sebastian Stan as Tonya's psychopath boyfriend/husband.

Small beer, perhaps, by the side of the two diamonds, but both beautifully crafted and acted gems. By the way, I was about to pass another evening in hospital by going to see Mary Poppins Returns in the amazing Medicinema of Chelsea & Westminster, but I was discharged two hours earlier; my 'second musketeer' pal in the bed opposite went instead with his granddaughter, and (as he told me when I popped in to see him on Tuesday) was surprised by how good it was. As I'm still awaiting the op, I'm entitled to revisit and was going to see The Favourite on Thursday evening, but that was one of my bad days so I stayed home. Outings need to be carefully spaced at the moment, though I'm proud to have made, and reviewed, two events this week: Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades at the Royal Opera on Sunday afternoon, and Bang on a Can's Friday night cornucopia at Kings Place.

Friday, 18 January 2019

Bucked up by The Valkyrie

As the hospitalisation dragged on, I realised I'd have to postpone the start of my 10 Opera in Depth classes on Wagner's Die Walküre this term by a week. Of course coming home is often more tiring than you expect, and the stent is a nuisance, especially when you have to carry your class kit of heavy books and scores in a rucksack - I'm not up to cycling, probably won't be until after the op - but I felt I could battle that and found myself inspired by the preparatory reading. As I was by the musical side, at least, of the Royal Opera's Queen of Spades on Sunday afternoon, my first outing since I left C&W three days earlier.

I have on the shelves the Poetic and Prose Eddas in several translations as well as the Nibelungenlied, but I only recently bought the neat little Penguin edition of The Saga of the Volsungs which was Wagner's sole source for the tragic history of Siegfried's parents.

As always, one has to marvel at how he followed in the footsteps of the great mythic reworkers (Sophocles and Euripides, for starters) in adapting brutal material to a more compassionate end. You have to take your hat off to the warring, scheming women in this saga, but surely you draw the line at infanticide: Signy, the Sieglinde character, bumps off, or has bumped off, four of her children by a man she doesn't love, but Gudrun, the Gutrune character, takes the biscuit in serving up the Attila figure the hearts of their children on a spit. Pure Titus Andronicus.

So much for the great incestuous love story of the siblings who fall in love before they know (consciously, at any rate) who they are: Signy changes shape with a witch, goes in disguise to her brother Sigmund in the forest and sleeps with the unknowing hero, presumably to 'get with child' and produce something that will grow up to be a Real Man. That's not Siegfried; he - as Sigurd - is Sigmund's son by a third marriage some time after Signy has accepted her guilt in getting what she wanted and shuffled off this mortal coil. There are also several generations between Odin/Wotan and his beloved Volsung. Clever Wagner to make the terrible twins Wotan's own children.

I always stress to students that most studies of The Ring deal too much with the sources and the libretto, and not enough with the music. If only Deryck Cooke had lived long enough to get to the musical side of I Saw the World End; the torso we have is still my primary secondary source, as it were. Which is why we're going through each opera, starting with Das Rheingold last January, scene by scene, theme by theme, highlighting all the most interesting musical transformations. But it was high time to get to closer grips with the original myths. Wagner left behind a seminal letter highlighting his particular interest in the Volsung Saga before recapping his method of writing the 'book' backwards and then the four operas in chronological sequence.

So far we've only taken Siegmund through the storm. The opening has to be more running than trudging through mud; some conductors just don't get it, but Karajan and Böhm are superbly graphic. More minimalist music, unmodulating for a while, just like the Rhine Prelude and the Entry of the Gods into Valhalla. You could - and I did - spend half a class just talking about and illustrating that, with its roots in Rheingold. I also traced the major themes of the act as they unfold in Siegfried's Funeral March. There I chose the other extreme - Reginald Goodall's first recording of excerpts from the final opera with what was then the Sadler's Wells Opera Orchestra. The brass playing is in a league of its own.

Next week - on to the lurve. Anyway, it's so good to be back in Pushkin House, with its helpful staff - shame about the decadence of the Frontline Club after Ian Tesh's departure, much as I love the place - and to feel the support of my wonderful, responsive and devoted students. It's not too late to join us - e-mail me at david.nice@theartsdesk.com if you're interested, but you might also feel like signing up with the Wagner Society of Scotland for its Trossachs retreat in September. The good news is that after stepping in at the last minute in 2018 and proposing Rheingold because I had already prepared, I'm booked for the next three years. And I won't simply repeat myself up there - so much thinking about Wagner always goes on between engagements.

Friday, 11 January 2019

Released, with gratitude

...for all the fine nursing and good company I've enjoyed - yes, enjoyed - during my 14 days in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital (this by way of a corrective to the horrors of the last two posts, accompanied by photos of the five-star-hotel view from my bed. The one above features the most original pick-me-up, Jonny Brown's two-piece vase of tulips from Duranus). Finally, after 48 hours' prevarication when my temperature stabilised, they performed the 'second intervention' on me to remove bag and tube into my left kidney - medical term 'nephrostomy' - and replaced it with a stent, which is more uncomfortable on the nether regions but gets me out of jail. Which I left at just after 6 yesterday evening, saying a rather reluctant farewell to the two other musketeers in Bay 6 of the ward. We three were wryly dedicated to reprimanding the moaners and complainers, telling them the nurses were doing their best and that there were other folk on the ward much worse off than them whom they needed to consider.

So, a hymn to those guys and to two others. My long-term neighbour, whom I'm sure I can name, Mr Patel, went through a lot of suffering and still needs his gall bladder removing, but he was a smiling and warm personage throughout it all. Among his several professions he runs an organic olive oil farm in Puglia. He'd asked his business partner to send a bottle; he delivered 16, so they went to the staff and to us three musketeers when he left about a week ago. I shall be heading up to the wondrous Neasden Hindu Temple for some vegetarian food in the next month.

I mentioned noble John, 94, pillar of the Iranian Christian community in London. He knew the people we'd heard about during our most extraordinary Christmas Day with the gated Anglican community in Isfahan, having managed a hotel there before being forced to flee during the revolution (that same which brought tragedy to the then-Bishop, his son stoned to death by an angry mob). I was very much moved by John's journey, after the latest of his many falls which fractured his skull, from seeming at death's door to being up and shaving himself, to retreat and then, it seemed, to full lively recovery, and I enjoyed conversations with two of his daughters*.

Memorable indeed was the afternoon when the Bishop of Iraq, who had been due to stay with John, came in with a group of friends, in the middle of which a celebrated Chelsea doyenne, artist and writer, another patient, wandered in sporting her afternoon glitter and feathers. Less happy was the night when John fell out of bed. Twice. Why hadn't they put the side guards up? I got a complicated explanation about how the patient can harm him- or herself more getting tangled in them. Anyway, fiercely independent John will need 24 hour care when he leaves, which he may already have done; he was moved to another ward five days ago.*

What a contrast to the two horrid old men who occupied the bed opposite him in succession. I've written about the Screamcougher, but maybe there was something psychologically amiss. Next was a fully compos mentis old moaner and attention-seeker who wanted to get back to his cat. Treated half the staff, who were infinitely patient with him and polite, very vehemently ('leave me alone!' 'What do you think you're doing?' 'Where's the fucking doctor'?). Just occasionally made us laugh ('I want to shit, dear'). Asked us all to help him. I gave him a banana - he always wanted more at breakfast, lunch and dinner - but there was a moment of pure black comedy when he asked Musketeer Two to help him get up. 'I've got terminal cancer, man, you're asking the wrong person'. I gave him a speech, addressing him as 'sir' and telling him this was not a five-star hotel and that the staff were doing their best under difficult circumstances. He stared at me open-mouthed but did shut up for the rest of the afternoon.

Musketeer Two (if I am One, in absolutely no order of priority), old hippy, has done a lot of drugs in his life, involved in the music business and just back from Jamaica. Very gentle and kindly, huge array of visitors, coming to terms with a diagnosis of cancer spread from kidney to liver and lungs. I joked that he was 'making a molehill out of a mountain'. Musketeer Three arrived the day after me. Crabby and laconic, but always surprising. In a lot of pain after treatment for a burst appendix. With a wife who had her own lung problems so couldn't visit often. Heard him waiting for her on the phone: 'where are you, you silly old cow?' But to my surprise we were all singing from the same hymn sheet on Brexit and Trump. I left before I could get to see Mary Poppins Returns in the MediCinema (another of C&W's fabulous setups); he went instead with his granddaughter. Next Thursday is The Favourite, which being on the lists I can go and see with a friend for free. Unfortunately J does not want to set foot inside the hospital again. Anyway, Musketeer Three and I chuckled quietly on a regular basis, bitching about the troublemakers.

I thank so many of the nursing staff. Some were indifferent - what a difference introductions would have made, given that the team of two serving the ward changed daily and nightly. Only three were fairly-to-downright useless. I've already mentioned the exchange with the mystery woman at the desk and the male nurse who failed to screw up the bottom of my bag after emptying so it went all over the floor, also referenced under 'Screamcougher and squalor'. Like many of the staff, he was always on Instagram and Facebook, looking at cars and sports. Jeremy found him fast asleep at the desk in the middle of the afternoon.

One night nurse who was busy on Facebook at her desk said, when I pointed to my three-quarters-full bag on my way out from the toilet, 'I'll come when I've finished this'. 40 minutes later she appeared in the ward and said, 'I haven't forgotten', before walking out again. When it reached full to bursting I went to the toilet and emptied it myself. She looked disapproving when I told her I had to do it (as I had been, before they decided they wanted to measure and/or analyse the contents). 'An hour has passed', I said, knowing it was between 50 minutes and an hour or more. 'Not an hour,' she said, walking away again. One other nurse was rude (when I asked politely about making up the bed, usually done around 10am but this time unmade way past noon, 'let us do our job') but clearly good at his work, and we got on better after that. I could have done without the ineptitude of a too-tight dressing which was apparently the real reason for blistering on my right forearm and cellulitis above it. That retreated swiftish, but the extra hospital contributions to my suffering were unnecessary and unwelcome.

I repeat - that stuff was very much in the minority. I thank the majority, dealing well in situations of serious understaffing, from the bottom of my heart. One thing I shall be on the warpath about: the hygiene.

Cleaning the few toilets and showers shared by the ward only three times a day - twice, in this instance, it seems (photographed at 21.30 that night; on the next morning, the third entry was filled in, possibly fraudulently) - with the last cleaning usually at 2.30pm. Contracting out to an inadequate company is false, short-term economy; stamp out the chance of MRSA etc and in the long term the NHS saves money.

While nights proved a trial - I can't get over the silence back home - days were never boring. My reading tailed off a bit after finishing the Ferrante quartet; an earlier novel, The Days of Abandonment, is of the highest literary quality, a Kafkaesque narrative of how a woman loses her sense of self and falls into absurd, irrational behaviour after her husband abruptly leaves her for a younger model, but not a pageturner. My most recent visitor apart from J, the wonderful Frances Stonor Saunders, brought me Virginia Woolf's On Being Ill, an astonishingly rich essay for its 24 pages.

Frances also offered invaluable advice based on experience: when you leave, ask for a full printout of your treatment rather than just the usual signing-off summary. Papers go missing; when you return for any connected appointments, bring it all with you just in case.

I finished one fine TV series and got through a shorter, more recent one. Earlier this year, I was drawn in immediately to Eve Myles' utterly mesmerising, infinitely various characterisation, the core of the Welsh thriller Keeping Faith.

How bereft I'd felt when it went off the BBC iPlayer in September as soon as I'd got to the end of episode 4 (of 8). Fortunately I found the rest this time by entering 'Keeping Faith watch online' into Google, happy to put up wih the odd interjection of an advert in each instalment. The slow burn, always plausible drama maintained its high standards to the end, with all the other roles superbly taken (plenty of stillness, a rare quality in TV acting. Pictured below, Myles with Hanna Daniel as Faith's sassy fellow lawyer Cerys Jones). Roll on Series Two.

After that I turned to The ABC Murders, well aware that Agatha Christie adapter Sarah Phelps always serves up thoughtful rewriting (and replotting in some cases) since I reviewed And Then There Were None for The Arts Desk. Malkovich as Poirot? Ungenial, perhaps not Christie's detective, but a magnificent and compelling creation, so watchful.

All acting fine, cinematography beautiful or grim to look at (though they seem to have taken a bit of a train going through a landscape from last year's Scotland-set Witness for the Prosecution; no routes to the south coast from London look remotely like that). The original is one of the few I never read, so the twist came as a genuine surprise; I don't expect anyone would anticipate it.

Got to the end just before they wheeled me down for the second intervention, less painful than the first though I wished I didn't have to hear every word of the surgeon and assistants; I was trying to focus on the closing scene of Strauss's Daphne in my head. Now I just have to wait in line for the stonebreaking, which of course was done in a day two and a half years ago along with the rest in the Acibadem Private Hospital, Bodrum, Turkey. I'm afraid that because of NHS waiting times, worse than ever for cancer patients as The Guardian states today, I'm going to take up the very reasonably priced private healthcare plan J has just discovered.

*I bumped into one of them, Caroline, in the lift on my return visit this Tuesday to give a sample and blood, and though we were delighted to see each other, I was sorry to hear that John, now in a ward one floor below, has been up and down (and still there, though we had talked about options for temporary care home - my 90 year old friend Thomas, now bereft of Beulah who went there with him, is in the permanent part of what sounds like a very good one in Wimbledon).

Monday, 7 January 2019

Screamcougher and squalor

4.30am, and I shan't sleep, so here's a real-time rant from the heart of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. Apart from the visitation of the manacled maniac - see the previous post - the worst here is the emaciated gentleman on the ward who coughs and retches for hours on end. Three nights ago I got two hours sleep. Then it was agreed that for his own sake as well as ours, since he didn't seem to have slept for 24 hours, a sleeping tablet would be best (with his agreement). That hasn't had much effect in the small hours today. I went to read in the TV room for half an hour around 3.30am, but it hadn't abated when I got back. The nurse just gave him something else and it all went silent for about 10 minutes, but it's started up again. In between we get 'Oh my God', 'Yallah, yallah', 'The end must come', 'What a dump', 'It's so hot in here' - and I'm not even sure if it's delirium, for he responds rationally if rudely to treatment.

So in the midst of all this I finally snapped. I went to the bathroom at 3am, trailing my drip-feed antibiotics on a stand attached to the cannula in my arm as well as my bag and tube attached to the left kidney. It seemed that one of the connections had come out, and the feed was dripping on to the bottom of the stand. A girl in blue I hadn't seen before was sitting at the desk outside our bay.

'I think one of these has come out,' say I, pointing to the tubes.

'I don't understand what you mean'.

'This - what I'm pointing at'.

'I have no idea what you're talking about. I don't work here [literally true, since like most folk I've seen in the small hours, she was looking at her Instagram account, but she was employed there, if only to tide over short staffing in the night shift]. You'd better ask someone else'.

Would you blame me for losing it?

Our night nurse is very good at his job, but he was on a break. There seemed to be only one nurse for all six bays, so it took another 10 minutes for her to come.

So many good people here, but in the last few days I've encountered two of the don't-cares. The other is an agency nurse who emptied my bag but left the nozzle untightened, so stuff leaked over the floor. When I told him he'd forgotten to tighten it, he said 'they work their way loose'. I said, no, that wasn't the case. A shrug, no apology.

My other beef is the squalor of the lavatories and bathrooms. An outside agency comes in three times a day to 'clean' (I've seen how perfunctory that is in the bays themselves, and the other day J and I were sitting in the Costa coffee bar downstairs on my daily excursion when a man with a wet mop came up, made a few wet patches and left all the floor around them, including all the food under the tables, untouched). The last appearance of its staff is at 2.30pm. So if, as happened the other day, someone comes in, drips blood, leaves discarded towels, gowns and swabs on the floor, etc, the bathroom can be left uncleaned until 8am the next morning .The nursing staff aren't allowed to remove the detritus, It makes me rage, this false economy. A Belgian friend tells us that hospitals there don't have our MRSA problem because they have 24-hour on site cleaners. And isn't hygiene in a hospital as important as the actual nursing? Joseph Lister would despair.

8.30am While the rest of us are prostrate after an exhausting night, our screamcougher is asked by the visiting doctor how he feels and says 'fine' (later, to a Chelsea Hospital administrator who said ' I hear you've been in some pain', he said, 'no, only a slight ache'). The plus is that they're sending him back to the unfortunate institution where he must make everyone else's lives hell. I addressed him this morning, 'Sir, I'm extremely sorry for your unfortunate cough but could you please tone down the complaining, There are a lot of people in here worse off than you' Mutterings and imprecations, but it worked - for 15 minutes. Anyway, they're coming to take him away shortly.

Friday, 4 January 2019

New Year on the ward

Entering my ninth day in a ward (I'm told not to name it) of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, which makes me the oldest lag. And what haven't I seen over this period, waiting for my temperature to go down so that the tube and bag from my left kidney, infected from another trapped stone - for the first incident in Turkey, see here - can be replaced with a stent.I pick up fragments of stories from patients in the other five beds - huge imaginative possibilities even when surface-undramatic.

First we were three, a quiet far eastern Christian with friendly visitors, an equally quiet Muslim gentleman who had imam's prayers sounding from some device at the key times of day and his head bandaged from an assault (racist? It seemed unlikely he'd get in an attack himself). Next to join us, a dude with a manbun and a hand injury that required plastic surgery. Lived behind the screen rattling away in conversation with his girlfriend for 10 hours; when they snuck out, I knew it was for his daily cannabis fix despite explicit instructions from the medical team that he mustn't smoke anything. The next day it all went wrong between them after one such excursion - a barrage of French expletives from him drove her away, then she tried phoning the desk, and he said he wouldn't speak to her because she was drunk. He left the following morning, unaccompanied.

Supreme drama: 5.30am, a manacled maniac loud with apparent pain, two police officers at the foot of his bed. At 6 I couldn't bear more and went and sat in the telly room while he kept setting off the alarms and causing further havoc. I was stonewalled when I asked if they couldn't give him powerful enough sedatives. I only got a fuller story from a nice nurse three days later: he'd been arrested in possession of a knife and cocaine, and as soon as he was locked up immediately 'developed' this agonising pain. Obliged to take it seriously lest they had a death on their hands, the police brought him here, tests were made, nothing found. Interesting how he quickly moved from imprecations and 'you don't know what pain I'm in' (to me, when I finally said 'shut the f**k up', and I replied 'try me') to abusing the doctor who'd treated him and asking for his number (narrated the 'he took my trousers and pants down' with a demonstration the screen thankfully prevented me from seeing. 'Stop, sir, there are other patients here,' said one of the patient policemen. He was treated with remarkable courtesy by the professionals, not by me). Drug addict or psychotic or both? We shall never know, because finally, at 11.30am, he was carted back into custody and peace reigned for a bit.

Nights are never quiet here, yet I could only feel relieved that the next admission to that bed didn't arrive, similarly, until 5.30am and proceeded to retch violently for the next few hours. Skinny, shaven-headed and tattooed in black like a Siberian prisoner, he seemed gentle and soft spoken, though in major medical trouble. A couple of hours into New Year's Day, he apparently took out all his tubes and left. The nice bay nurse for the next stint established from his wife that he'd gone home, but he had to be readmitted that night (though not to our section).

His neighbour was a gentle youth from a posh family, possibly 17, well tended by his nice girlfriend. Returning from his appendectomy, his skin was the pallor of the poet in 'The Death of Chatterton', so Chatterton he became among us.

Moved to a bed by the window of the bay at the other end of the ward, I'm now in what is otherwise a geriatric ensemble. My hero is old John, 94, admitted with a fractured skull after falling over, believed by his two daughters to be at death's door ('come and see him, he may not last' was one phone conversation). The next morning he was up, asked to shave, decided to take sugar in his tea because it wasn't very nice and talked about receiving 'the Bishop' in his home for the weekend's church assembly. Difficult to converse with him because he keeps his hearing aids out until the daughters arrive in the afternoon. Wish I could have done so last night, because a Chelsea Pensioner newly admitted, loving to talk about the army and how he laid communications for the British army in Afghanistan, had a screaming cough accompanied by groaning all night.

The rest of us are quieter. I so like my genial neighbour, such a nice man, and even the querulous gentleman opposite him who is giving the folk here a very hard time is well-intentioned towards the rest of us. But how he snores! Last night I discovered this,

and it smothered all noises other than the screamcoughing. So I still only got two hours' sleep. Well, on to the end of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan quartet, which has been an ever-increasing source of wonder, and to the conclusion of another teatralogy, the BBC Radio 3 broadcast of Götterdämmerung Act 3; yesterday was the first when I actually wanted to listen to music. Meanwhile I wait for my temperature to stop 'spiking' before having any chance of going home.