Showing posts with label Jonathon Brown. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jonathon Brown. Show all posts

Friday, 10 February 2017

Still life in a turbulent time

Right at the heart of the colourful riot that is the Royal Academy of Arts' Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932, in a room devoted entirely to the unique style of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, my eye was drawn to this still life of 1918. I knew several others of his, but not the extraordinary treatment he lends to a herring, a couple of potatoes and a lump of bread - the restricted fare of hard times.

It's the artist's prerogative to lend grace to the ordinary in a nutshell. A parallel struck me the day after seeing the exhibition at a point I reached in Péter Esterházy's Celestial Harmonies - not easy reading, but every page of this discursive take on the author's very famous family deserves to be savoured, and a lightness of touch mitigates the difficulty of grasping such allusice richness. His father, under the straitened circumstances in which the family finds itself under Communism, is making a drama of preparing to attack a bone for its marrow by extracting it from the cooking pot.

'The midnight predators gather for the kill,' our father announced mock-heroically, then sat down at the kitchen table with ceremony, the pot in front of him. We crowded around him, buzzing and craning our necks, so we shouldn't miss anything. 'Take your places,' he said, looking at us with make-believe severity and then, like a chief physician at the operating table (or a priest conducting mass), he raised his two hands. 'The scalpel, sweetheart!' he said to mother, who did and did not take part in the show. She was happy that we were happy, we, her children, and also the man who at that moment was busy pretending that life is beautiful and exciting, and he the master of all he surveys, the benefactor of the small group for whose benefit he was demonstrating that this beauty and excitement is everywhere at all times: just look, even in a bone, a leg of beef!

And perhaps it's not even pretending so much as creating, on both the author's and his father's part. By the same token, Petrov-Vodkin wraps magic around the ordinary in the RA room devoted to his work, an exhibition-within-an-exhibition. Of course there are questions around the stunt as a whole: the plutocrats and the Russian governmental propagandists making the exhibition possible with a stunning array of the best - Moscow and St Petersburg galleries must be bare of their post-revolutionary masterpieces at the moment - as well as the questionable aspects of celebrating a vision that quickly soured. A grim 'Room of Memory' at the end, showing 'criminal' mugshots of many who were murdered under Lenin and Stalin, attempts to make amends.

But surely the point is the unleashing of energy, good or bad, into kinetic art. For, despite the stillness in the leading image, all is movement in this exhibition. And there are some impressive novelties which fit the giant RA rooms so well: the recreation of an El Lissitzky workers' room in the 'Brave New World' gallery, which is more coherent than it looks here

and above all the magnificent attempt at reassembling Malevich's room of his own work for the 1932 exhibition 'Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republics'. Not even the recent Malevich show at Tate Modern managed this.

The RA has gathered together most of those original works - with, I think I'm right in saying, only two substitutions - and recreated the models; the effect is very impressive, possibly more so than the original, of which we do have a photograph.

Otherwise, the revelations to me were the Petrov-Vodkin collection, the ceramics and the work of one artist with whom I wasn't familiar, Alexander Deineka - variable, but this one of textile workers fascinated me.

For the rest, it was a bracing reacquaintance with many old friends, and nostalgic memories especially of many hours spent in St Petersburg's Russian Museum - a more essential gallery for the understanding of the native culture, certainly, than the breathtaking Hermitage.

We leaped from one exhibition to another, the David Hockney retrospective at Tate Britain, for an intimate little gathering of 2000 or so folk thinking they were going to get a close audience with the master. Actually we did, since when we arrived the queues to get in to the exhibition proper were enormous, and - diverted by good company - we suddenly found ourselves with only 15 minutes to rush around. So the first two rooms, with pictures of the ilk of 'We Two Boys Together Clinging', which impacted so much on me as a teenager, were empty, and in the third our only companions were Ian McKellen and Neil Tennant, chatting - appropriately enough - in front of the theatrical 'Ventriloquist' canvas.

The whirl wouldn't have worked if we hadn't already been so familiar with many of the canvases, and seen so many in previous exhibitions, but no doubt about it - this would have to be the most impressive in terms of together-hanging, above all in the room of heyday swimming-pool paintings and double portraits.

Then it's on to the exquisite drawings, his best portraits (Auden and mum especially) followed by the photomontages (mum, again, at Whitby Abbey my favourite) and the last room with stuff I really love, the colourful road pictures.

And these two of still lives - only connect - by the sea; I didn't know them. I hope these people will forgive their featuring in my general impression.

On to the English nature pictures, the paint rather gauchely applied IMO,

and to the less interesting final rooms. As Hockney's old pal and ours (of lesser years) Jonny Brown observed, it must have been the artist's choice not to include his (again IMO) terrible later portraits (the National Gallery wardens must be the worst). Here's Jonny with the ever-amazing wise young bird Thierry Alexandre by Millais' Ophelia

in the dreadfully-hung and badly-lit Tate Britain room mixing Pre-Raphaelites with really superior stuff like several of Whistler's Nocturnes. And Thierry allows me to transition to something I should have written about months ago, beloved artist Paul Ryan's show on the impact of InterRailing at Europe House's 12 Star Gallery. Here's the diva/o's back, in the first of the portraits here taken by the 12 Star's resident photographer,

and further portraits in front of some of the exhibits: the artist flanked by myself on the left and dear Chris Gunness with my goddog (by which I mean I am his godfather) Teddy on the right,

the great Jeremy Deller alongside his InterRail exhibit,

composer David Sawer with the manuscript of an early work written in the wake of an InterRailing experience,

and Lady C with her dog - I had to leave for Richard Jones's production of Once in a Lifetime so didn't get to meet them - in front of hers.

It all brought back memories of happy days in which I discovered the joys of independent travel - first under the organisational aegis of Christopher Lambton, who worked out our train journey to Istanbul and back, with a further loop by other transports in the wake of the military coup around the west coast, in 1981; and then, the following summer, the revelation of how good it was to travel alone, and feel completely free, after I left friend Simon at Ravenna and travelled on to Padua, Venice and Vienna with Bertrand Russell's The Pursuit of Happiness confirming the source of my joy.

Tuesday, 18 December 2012

Books - for cooks?

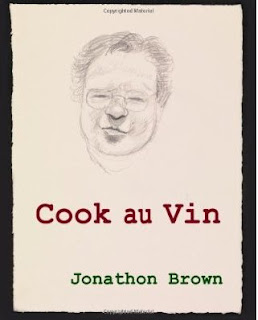

Probably not, in the case of our flamboyant friend and

artist and Lord High just about Everything Else Jonny’s samizdat ramble. Given a

style which is very much the man as he holds forth, Cook au Vin deserves to be

hailed as the Tristram Shandy of its ilk. And it really should be read from

cover to cover (the illustration above is by his pal David Hockney, perhaps not one of his best...). From his fastness in the foothills of the Alpes maritimes above

Nice, the Broon has compiled recipes of sorts with a little help from friends

with mysterious names such as ‘The Saintly’, J-J and Chinkers (one of the few

to be properly introduced to us). So beguiling are the digressions that I was

almost disappointed when we finally reached ‘Appetizers and Aperitifs’.

I needn’t have worried. The footnotes and the Chinese-box

off-pistes continue. Musing on the order of wine serving, JB floats back to Edinburgh in the 1980s –

which is where I met him – and a Queen’s Hall recital by Roger Woodward; he’d

written the notes in chronological order for a programme of three Chopin

sonatas, only to find that Woodward had decided to play them 3-2-1. But before

we get to discover the reason, there’s a note on why artists’ Green Rooms are so

called, and after it another on Woodward carving a duck ‘like a swashbuckler

from a Chopin Polonaise’. Here's a snap I took of the author at a splendid Edinburgh Gesamtkunstwerk event to launch his roadmovies exhibition and book (J sang Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, amongst other musical plums).

The food? Well, you’d probably eat it. We have, on various

excursions to Duranus - that's me looking bleary and unwashed below with my morning coffee after a night on the floor of JB's record room - though I remember the gaggle of weird guests rather than

the flavours (how could I forget Belinda and Belinda, who were writing a book

called Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll: A Year in Provence? ‘It’s in real time’, they told us,

‘and you’ll be in it’. Given our failure to click, it’s probably a mercy that

said publication does not appear to have reached the light of day).

At least the advice on ingredients is probably sound. Thereafter they are mashed into what JB calls ‘gunk’ spread on bread or else pickled in various kinds of alcohol (James Hamilton Paterson’s semi-dud Cooking with Fernet Branca springs to mind – does Jonny know this book?) OK, so the worst is definitely tongue in cheek, the ‘gunk’ for pan-fried foie gras wittily titled ‘Sauce tirée des boîtes’ – the boxes in question containing fish fingers and cornflakes, preferably mixed with retsina. This priceless volume, complete with plenty of JB's artworks like the one below and reproduced bottom-of-wineglass stains, is printed to order by Brown Paper Editions. Apply to villaparasol@aol.com or (less preferably) buy a copy from Amazon.

A step up the evolutionary ladder is the beautifully

produced three-tone Goodbye Cockroach Pie from London friends Rosanna Kelly and Casilda

Grigg, celebrating the launch of Rosanna's Inky Paws Press. It stems from a 1986 discussion around the same Dundas Street (Edinburgh)

kitchen table I had only recently deserted for London after graduation. Rosanna

and law student Gail Halliburton mooted the idea of a cookbook especially

aimed at students. They gleaned many vintage recipes from friends, but the idea

hung fire until this year when the concoctions were refreshed and punctuated

with jolly illustrations.

Very well, so this Carabosse is in mild dudgeon not to have

been asked for his perfect student recipe. Needless to say I no longer cook it,

but it became a staple in the Dundas

Street kitchen: a fish curry consisting of smoked

mackerel (!), cooking apples, desiccated coconut, onions and the usual powders.

Decidedly an improvement on the meat loaf cooked with a lump of lard in it by

flatmates Mary and Helly, or the Spaghetti Carbonara of Simon without the

carbonara. I blush to think of the pride with which I served up to visiting

mother and stepfather gammon and pineapple. Happy days, as the delightful

co-winner (hurrah, a woman!) of Masterchef: The Professionals would put it.

This has not been the best of years for reading, but the

finest is probably what I’ve now reached: Ludmila Ulitskaya’s Sonechka – A

Novella and Stories. The shorter form seems to suit this author best: she is

so keen to give us her many heroines’ backstories that a longer novel like

Medea and Her Sisters can get overloaded by multiple strands. But what

compelling histories these are, usually tales of fortitude in the face of

adverse Russian circumstances and – unfashionably – of happiness descending in

time from banal or manipulative situations.

Within a couple of pages bookwormish Sonechka, her big

breasts her only physical asset, is courted by an equally unlikely artist and

soon can’t believe the joy to be found in the mundane. Zurich magics up a love story between a

Russian girl looking for a westerner and a westerner looking for a one-night

stand. The outcome of The Queen of Spades, its nonagenarian matriarch

tyrannizing her daughter and granddaughter much as the Countess tyrannises Lisa

in Pushkin’s short story, is less happy, but emancipation is so close at hand.

I so want to read more by Ulitskaya, but currently only The Funeral Party is

translated into English, and my Russian probably wouldn’t be up to Imago, which

Vladimir Jurowski selected as one of his 2011 summer reading books for The ArtsDesk.

Before Ulitskaya, I’d had something of a Patrick Gale binge,

with a slight sense of diminishing returns as I worked my way back from the

most recent to the earlier novels. Gale excels in his polyphony of family

voices and sense of place, especially Cornwall

in the two I enjoyed the most, A Perfectly Good Man and Notes from an Exhibition. No

doubt if he’d tackled the subject matter of The Facts of Life today, he’d have cut and

shuffled voices and times more flexibly than he did back in 1995. The jackets

and the Richard and Judy commendation do tend to put these books at lower than their real value. For once, here’s

a novelist who incorporates music and – as far as I can tell – art with real

understanding, who usually has a sympathetic gay character or two but doesn’t

necessarily make us see the world entirely from their point of view. I know I’d

like him as a person, and there are plenty more novels for cosy company when I

wish.

Otherwise, I don’t know why I was so compelled by the

sometimes dodgy preaching of Bunyan in The Pilgrim’s Progress, Part Two of

which I’ve also read since the Vaughan Williams stint, and I’m not sure whether

I was in the right mood when I read Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies, but

the Boleyn saga didn’t seem to me quite as singular as Wolf Hall. Music book of

the year – not that I’ve read many – is Anthony Phillips’s superb translation

and footnoting of the Prokofiev Diaries, Volume Three. But further comment on

that had better wait until after the BBC Music Magazine review appears. Other reading highlights of the year here and here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)