Showing posts with label Philip Roth. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Philip Roth. Show all posts

Friday, 29 July 2016

Plots against America

That's Charles Lindbergh on the left, the famous aviator who was to lead the America First campaign and decry 'the Jewish race' for trying to lead his country into the Second World War, in the delightful company of Hermann Goering, presumably at the time of the October 1938 dinner in Berlin where Goering presented Lindbergh with the Service Cross of the Golden Eagle. No such photos of Trump with Putin have come to light, prompting some amusingly creative collages which I assume are copyright so won't use here. But you can be sure that if the world's worst-case-scenario comes true and Trump is elected, he'll be holding meetings with Putin like the one Philip Roth imagines a putative President Lindbergh having with Hitler in Iceland, and later with Von Ribbentrop in the White House, in The Plot Against America.

There are probably more differences between Trump and Lindbergh than similarities - no-one sees DT as a clever operator hiding behind others, for instance. But it seemed timely to read this what-if masterpiece of a novel by a great American under present circumstances. Apart from the lethally eloquent and/or direct prose style, Roth's genius is to put himself and his family into the alternative picture, building on the anti-Semitism he experienced in New Jersey as a child.

I can't tell which of the friends and relatives gathered around the Roths are real - would love to read a biography or an alternative study which sheds light on this - but the portraits of his honest ma and pa break the heart. It isn't easy to make ordinary decency that interesting, but put it up against its opposite and you have some powerful situations. If you don't think you want to work your way through the whole book - amazing how people keep on saying 'I don't have the time to read'; there is ALWAYS time to read - then the second chapter. 'Loudmouth Jew (November 1940-June 1941)', about the Roth family visit to Washington and the anti-Semitism they experience there, is a locus classicus of vivid writing. Roth also makes some powerful statements throughout the book about the kind of man his father was, both as an American Jew and as a Mensch. More often he highlights what he was not:

It went without saying that Mr Mawhinney was a Christian, a long-standing member of the great overpowering majority that fought the revolution and founded the nation and conquered the wilderness and subjugated the Indian and enslaved the Negro and emancipated the Negro and segregated the Negro, one of the good, clean, hardworking Christian millions who settled the frontier, tilled the farms, governed the states, sat in Congress, occupied the White House, amassed the wealth, possessed the land, owned the steel mills and the ball clubs and the railroads and the banks, even owned and oversaw the language, one of those unassailable Nordic and Anglo-Saxon Protestants who ran America and would always run it - generals, dignitaries, magnates, tycoons, the men who laid down the law and called the shots and read the riot act when they chose to - while my father, of course, was only a Jew.

Roth (pictured above) makes the distinction between his father and other Jews they knew, though:

For good or bad, the exalted egoism of an Abe Steinheim or an Uncle Monty or a Rabbi Bengelsdorf - conspicuously dynamic Jews, all seemingly propelled by their embattled status as the offspring of greenhorns to play the biggest role that they could commandeer as American men - was not in the makeup of my father, nor was there the slightest longing for supremacy, and so though personal pride was a driving force and his blend of fortitude and combativeness was heavily fueled, like theirs, by the grievances attending his origins as an impoverished kid other kids called a kike, it was enough for him to make something (rather than everything) of himself and to do so without wrecking the lives around him.

As for the Jews who in Roth's dystopia kowtow to Lindbergh (pictured above before the 1941 speech which in reality toppled him), there is a devastating portrait in the shape of Aunt Evelyn who marries the self-satisfied, self-compromised Rabbi Bengelsdorf.

As always with Aunt Evelyn, there was something very winning about her enthusiasm, though in the context of my household's confusion, I couldn't miss what was diabolical about it as well. Never in my life had I so harshly judged any adult - not my parents, not even Alvin or Uncle Monty - nor had I understood until then how the shameless vanity of utter fools can so strongly determine the fate of others.

One can't take it for granted, unfortunately, that more than half of voting Americans come to understand the same thing before it's too late. If they don't, the world will sufer from a regime that might be longer-lived than the fictional presidency of Lindbergh. In the meantime, here's hope

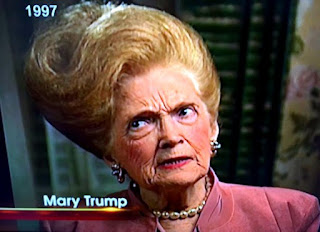

and here may be a greater part of the reason why Donald behaves as he does - behold The Mother.

Sunday, 16 March 2014

Arson bad, donuts good

Plunged recently into the alternating sweet and nightmarish American cityscapes of novelist A. M. Homes. Love her worlds or hate them - some are more extreme than others and, having been compelled to buy the entire oeuvre, J had to chuck the novella about a paedophile cannibal in the bin before it made him throw up - they're a racy read. The two I chose to follow in hot pursuit were the terrifying Music for Torching and the redemptive This Book Will Save Your Life.

I sense that by writing This Book... after Music for Torching Homes wanted to follow bad with good rather than present both facets in one volume, as Philip Roth does so devastatingly in American Pastoral. Here's another writer it was high time I started to read, and Simon Winder's declaration in the wonderful Danubia that Roth (Philip rather than Joseph, which might have been more appropriate for the context) was his own favourite author seemed like a good enough recommendation. Protagonist of this amazing Pulitzer Prize winner is Swede Levov, a genuinely nice guy and not even as limited as his sporting background and successful working life as family business heir might suggest. He's tolerant, liberal and utterly supportive to his only daughter. Yet it is she who, by one appalling action, 'transports him out of the longed-for American pastoral and into everything that is its antithesis and its enemy, into the fury, the violence, and the desperation of the counterpastoral - into the indigenous American berserk.'

Most of the book is devoted to Levov's imagination working feverish overtime trying to work out where he went wrong, what he has done to deserve it. And the only enlightenment, it seems, is this:

How to penetrate to the interior of people was some skill or capacity he did not possess. He just did not have the combination to that lock. Everybody who flashed the signs of goodness he took to be good. Everyone who flashed the signs of loyalty he took to be loyal. Everybody who flashed the signs of intelligence he took to be intelligent. And so he had failed to see into his daughter, failed to see into his wife, failed to see into his one and only mistress - probably had never even begun to see into himself. What was he, stripped of all the signs he flashed? People were standing up everywhere, shouting 'This is me! This is me!' Every time you looked at them they stood up and told you who they were, and the truth of it was that they had no more idea of who or what they were than he had. They believed their flashing signs too. They ought to be standing up and shouting, 'This isn't me! This isn't me!' They would if they had any decency. 'This isn't me!' Then you might know how to proceed through the flashing bullshit of this world.

Married couple Paul and Elaine in Homes' Music for Torching have no idea how to proceed through 'the flashing bullshit of this world' either, though it's not because they're too nice. They're falling apart, and the novel begins, as it were, with the denouement, which comes in the first chapter where Elaine kicks over the barbecue grill and sets fire to the house (no spoiler notice needed here. Homes pictured below by David Shankbone).

Where is the novel to go from here? Can this pair get any worse, give each other any more pain in their Strindbergian hell? Strictly, no, though the damage to the kids moves on apace and mostly unnoticed. Once in a while, they unexpectedly inspire pity and tenderness in us and in each other:

For the moment they are fantasies of themselves, their very best selves, the people they'd like to be, and then just a minute later they are once again their more familiar selves - petty, boring, limited.

Why doesn't either escape, get out of there? Homes' answer is that this is the only reality they know, even if it's hell and they are in it:

Every day Elaine thinks of disappearing. She will leave and take nothing with her - 'You have yourself' is what people say, and that's what stops her. She fears she is nothing. Nonexistent.

So even the liberating philosophy of Shakespeare's Parolles - 'simply the thing I am shall make me live' - has no validity in this modern identity crisis.

How on earth, then, to finish? Homes' solution is stagey, unconvincing (to me, at any rate), as if she just didn't know what to do: a consequence of the odd and, initially, daring structure. Roth, I think, has parallel problems. We observe 'the Swede' throughout the first part of the novel through an old school acquaintance, a familiar Roth alter ego (the author pictured below in 1973).

Who then disappears, leaving the author to retrace steps or rather go round in circles until we're stuck at a particular point in Levov's unhappy story where even more is about to go wrong. We know he survives it all outwardly because we've been told. But the ending towards the conclusion of a disastrous dinner party feels oddly inconclusive*.

Homes' This Book... follows a more comfortable trajectory, about a man in mid-life crisis who really does turn his world around with an honesty that would seem to have been alien to him up to the point at which the novel properly begins. Is it all too good to be true? Well, it's leavened with humour, irony and a surprisingly affectionate - when not scabrous - view of Los Angeles' looking-glass world. There's an unforgettable scene in which a horse gets stuck in a Beverly Hills sinkhole and has to be airlifted by the helicopter of a friendly neighbourhood movie star.

The arrivals on the scene of a housewife in meltdown and a reclusive Malibu writer warm the heart-cockles in an unexpected way; the hero's reunion with his son has 'feelgood movie rights' written all over it. Yet the exercise remains virtuosic, the unputdownable Homes pacy dialogue just as good as in Music for Torching, and above all it's creative donut shop owner Anhil who remains the good-angel constant. And that last photo? Well, we know that the French are turning against their own cuisine and so 'Les donuts, c'est la vie ' ought not to be too much of a surprise in central Lyon. Needless to say I didn't go in and buy one, but hived off to a patisserie in a sidestreet where I consumed...cannoli.

*With reason, it now turns out: see Sue Scheid's comment below.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)