Showing posts with label Hitler. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hitler. Show all posts

Thursday, 29 September 2016

A great Irish essayist

Not Swift, or probably any of the other names that spring readily to mind. I confess I hadn't heard of Hubert Butler until J came back from an evening devoted to him with a documentary I have yet to see at its core, clutching two of those beautifully produced books of essays which Notting Hill Editions do so well (I first read Thomas Bernhard in that format).

As a well-travelled multilinguist and a voice of Europe's terrible 20th century upheavals - he was born in 1900 and died in 1991 - Butler had a special angle to what he wrote. Hannah Arendt famously called it 'the banality of evil', and Butler - who sums up the essence of Eichmann in an essay if you don't think you can face Arendt's stupendous Eichmann in Jerusalem - puts it differently, time and again. 'It is the correlation of respectability and crime that nowadays has to be carefully investigated,' he writes in cool understatement.

The figure and the constellations around him who seem to sum it up most closely for Butler are Ante Pavelitch (we now write 'Pavelić'; pictured above), 'probably the vilest of all war criminals', the Croatian fascist dictator and leader of the terrible Ustaše movement, his Minister of the Interior Andrija Artukovitch (Artuković) and the Catholic clergy, most closely a Franciscan order, complicit and active in their crimes.

I don't think I knew of the enormity of all this - Pavelić features as a cool monster in a work of genius faction with odd ties to Butler, Curzio Malaparte's Kaputt - but Butler states it coolly: in 1941 the Croatian government, dedicated to the extermination not only of the Jews but also of fellow-Christians, the Serbian Orthodox, 'introduced laws which expelled them from Zagreb, confiscated their property and imposed the death penalty on those who sheltered them. Some 20 concentration camps were established in which they were exterminated'. The figures are of 30,000 Jews and 750,000 Orthodox massacred, some 240,000 Orthodox forcibly converted to Catholicism. Even if these figures are exaggerated, it was the most bloodthirsty religio-racial crusade in history, far surpassing anything achieved by Cromwell and the Spanish Inquisition' (below, Pavelitch and Archbishop Stepinac, Butler's paradigm of 'an ambitious, rather conventionally minded Croatian' capable of plentiful 'twists and turns...to keep pace with history').

Butler's special line of inquiry - and he was ostracised by the Irish establishment for establishing the truth - was to find out how and why Artukovich spent a year being sheltered in Ireland. The Franciscans provide the connection, though those to whom he spoke seemed ignorant of Artukovitch's status as a refugee war criminal and had, along with most clerics in Rome, 'been highly confused by what was happening in Croatia' (but this is an ironic swipe, because he goes on to point out that only one man in pursuit of the truth, Cardinal Tisserant, 'had a clear idea').

The gist is that 'if Artukovitch had to be carried half way round the earth on the wings of Christian charity, simply because he favoured the Church, then Christianity is dying. And if now, for ecumenical or other reasons, we are supposed to ask no questions about him, then it is already dead'. Butler enlarges on this in an early 'Report on Yugoslavia'. Deploring the 'hysterical adulation...poured forth by almost all the leading clergy upon Pavelitch', he adds:

As I believe that the Christian idiom is still the best in which peace and goodwill can be preached, I found this profoundly disturbing. I doubt now [1947] whether it is even wise for us to use the language of Christianity to the Yugoslav till all the vile things which were said and done in the name of Christ have been acknowledged and atoned for. I think the bitter hatred which is felt for the Churches in Yugoslavia is inflamed by all the lies and dissimulation about these things, by the refusal to admit that the Christian Church during the war connived at unspeakable crimes and departed very far from the language of Christ.

And in the central essay which gives Notting Hill Books' volume its title, 'The Invader Wore Slippers', he returns to the issue:

I felt that it was not the human disaster but the damage done to honoured words and thoughts that was most irreparable. The letter and the spirit had been wrested violently apart and a whole vocabulary of Christian goodness had been blown inside out like an umbrella in a thunderstorm.

The wider point being made in 'The Invader Wore Slippers' is how 'the moral problems of an occupation' turn out to be 'small and squalid'. Ordinary people are expecting jackboots; 'the respectable Xs, the patriotic Ys and the pious Zs' are unprepared for 'carpet slippers or patent leather pumps'. The Guernsey occupation is elegantly left to speak for itself - 'events for an October day in the first year of occupation [in the Guernsey Evening Post]: "Dog biscuits made locally. Table-tennis League of Six Teams formed. German orders relating to measures against Jews published. Silver Wedding anniversary of Mr and Mrs W J Bird."...Lubricated by familiar trivialities, the mind glided over what was barbarous and terrible.'

Not that the occupiers aren't skilful at winning complicity by double games. At one point Hitler is quoted on how to use the Church as his propagandists: 'Why should we quarrel? They will swallow anything provided they can keep their material advantages'.

Depressing instances abound. But Butler sees hope in the behaviours of small nations in which 'the Wicked Man is not yet woven so scientifically into the fabric of society', citing the ways Denmark and Bulgaria found to evade giving up their Jews in the Second World War. He praises the local community spirit, and in a long, brilliant interlude, 'Peter's Window' writes of his time living with a Leningrad family in 1931. Normality is celebrated, but its obverse is warningly inserted:

These are the things we talked about in Leningrad in 1931: spoons, buttons, macaroni, galoshes, macaroni again. I don't believe I ever heard anyone mention Magnitogorsk [pictured below: Komsomol meeting there the same year] or the liquidation of the Kulaks or any of the remote and monstrous contemporary happenings to which by a complicated chain of causes our lifestyle and our macaroni were linked.

At the end of that decade Butler was in Vienna working frantically with those admirable people the Quakers - he was not one himself - to find as many Jewish citizens as possible places abroad. He writes that, strangely, he was happy because all his faculties were engaged, and 'most people tied to a single job or profession die without exercising more than a tenth of their capacities'? The essay, after giving a devastating portrait of an Austrian Butler brought to Ireland, wheels round again to questions of the Catholic Church's role in World War 2.

So, an admirable man who acted in the maelstrom. But we wouldn't read him if his style wasn't so pure and, in its elegance, so capable of the sudden devastating sideswipe. His writing is the polar opposite of Patrick Leigh Fermor's flowery prose, and though I find the precision hard to emulate as an incorrigible sub-Jamesian, I salute it. Now to the volume of Ireland-based essays, The Eggman and the Fairies.

Friday, 29 July 2016

Plots against America

That's Charles Lindbergh on the left, the famous aviator who was to lead the America First campaign and decry 'the Jewish race' for trying to lead his country into the Second World War, in the delightful company of Hermann Goering, presumably at the time of the October 1938 dinner in Berlin where Goering presented Lindbergh with the Service Cross of the Golden Eagle. No such photos of Trump with Putin have come to light, prompting some amusingly creative collages which I assume are copyright so won't use here. But you can be sure that if the world's worst-case-scenario comes true and Trump is elected, he'll be holding meetings with Putin like the one Philip Roth imagines a putative President Lindbergh having with Hitler in Iceland, and later with Von Ribbentrop in the White House, in The Plot Against America.

There are probably more differences between Trump and Lindbergh than similarities - no-one sees DT as a clever operator hiding behind others, for instance. But it seemed timely to read this what-if masterpiece of a novel by a great American under present circumstances. Apart from the lethally eloquent and/or direct prose style, Roth's genius is to put himself and his family into the alternative picture, building on the anti-Semitism he experienced in New Jersey as a child.

I can't tell which of the friends and relatives gathered around the Roths are real - would love to read a biography or an alternative study which sheds light on this - but the portraits of his honest ma and pa break the heart. It isn't easy to make ordinary decency that interesting, but put it up against its opposite and you have some powerful situations. If you don't think you want to work your way through the whole book - amazing how people keep on saying 'I don't have the time to read'; there is ALWAYS time to read - then the second chapter. 'Loudmouth Jew (November 1940-June 1941)', about the Roth family visit to Washington and the anti-Semitism they experience there, is a locus classicus of vivid writing. Roth also makes some powerful statements throughout the book about the kind of man his father was, both as an American Jew and as a Mensch. More often he highlights what he was not:

It went without saying that Mr Mawhinney was a Christian, a long-standing member of the great overpowering majority that fought the revolution and founded the nation and conquered the wilderness and subjugated the Indian and enslaved the Negro and emancipated the Negro and segregated the Negro, one of the good, clean, hardworking Christian millions who settled the frontier, tilled the farms, governed the states, sat in Congress, occupied the White House, amassed the wealth, possessed the land, owned the steel mills and the ball clubs and the railroads and the banks, even owned and oversaw the language, one of those unassailable Nordic and Anglo-Saxon Protestants who ran America and would always run it - generals, dignitaries, magnates, tycoons, the men who laid down the law and called the shots and read the riot act when they chose to - while my father, of course, was only a Jew.

Roth (pictured above) makes the distinction between his father and other Jews they knew, though:

For good or bad, the exalted egoism of an Abe Steinheim or an Uncle Monty or a Rabbi Bengelsdorf - conspicuously dynamic Jews, all seemingly propelled by their embattled status as the offspring of greenhorns to play the biggest role that they could commandeer as American men - was not in the makeup of my father, nor was there the slightest longing for supremacy, and so though personal pride was a driving force and his blend of fortitude and combativeness was heavily fueled, like theirs, by the grievances attending his origins as an impoverished kid other kids called a kike, it was enough for him to make something (rather than everything) of himself and to do so without wrecking the lives around him.

As for the Jews who in Roth's dystopia kowtow to Lindbergh (pictured above before the 1941 speech which in reality toppled him), there is a devastating portrait in the shape of Aunt Evelyn who marries the self-satisfied, self-compromised Rabbi Bengelsdorf.

As always with Aunt Evelyn, there was something very winning about her enthusiasm, though in the context of my household's confusion, I couldn't miss what was diabolical about it as well. Never in my life had I so harshly judged any adult - not my parents, not even Alvin or Uncle Monty - nor had I understood until then how the shameless vanity of utter fools can so strongly determine the fate of others.

One can't take it for granted, unfortunately, that more than half of voting Americans come to understand the same thing before it's too late. If they don't, the world will sufer from a regime that might be longer-lived than the fictional presidency of Lindbergh. In the meantime, here's hope

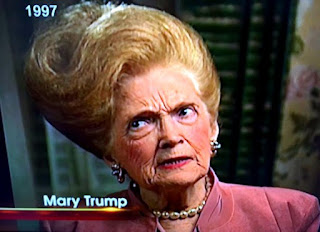

and here may be a greater part of the reason why Donald behaves as he does - behold The Mother.

Monday, 11 April 2011

Himmel über Berlin

That, of course, is how the Germans know Wim Wenders's Wings of Desire, a film which so coloured my early trips to this ever-changing city. Funny how each return can be tinted, or tainted, by other second-hand impressions: this time I couldn't get away from the ruined horrors of 1945, courtesy of Fallada's Alone in Berlin and Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones. To be honest, you don't have to look far beneath the shiny surface for signs of those times. Even the winged Victory, whose perch was also shared by Wenders's angels, is poised atop a sandstone-and-granite column heightened and moved by Hitler from outside the Reichstag to form the centrepiece of his east-west axis.

I suppose every city has its dualities, in any case: on the very day I was cycling through our own central greenlands and wondering at the new-budding trees, a body was fished out of the Serpentine. Cue diversionary snapshot.

Last Tuesday the weather in Berlin was so mild, if not as brilliant-blue as the above proves it soon was in London, that I gave up on museums and exhibitions, including an Ingmar Bergman special I really shouldn't have missed, and decided to walk from my hotel near the Philharmonie to Schloss Charlottenburg. I had four hours between my genial late-breakfast interview with Andrew Litton and the journey back to Schonefeld Airport, and it turned out to be quite a hike, by no means all of it pretty. From the leafing trees and wild flowers of the Tiergarten's south side

I crossed a couple of the roads meeting at the Siegessäule and found myself in a less salubrious woodland around the Fauler See. We're talking midday, but this zone was full of stunted and deformed eastern cruisers who kept on dropping out of the ugly tree. The hassle was so, well, I'll be frankly prudish and say disturbing, that I walked the rest of the way up to the Charlottenburger Tor along the road. Now there's another ugly beast for you, built in 1905 for the 200th anniversary of enlightened Queen Sophie Charlotte

but considerably adapted by Hitler in 1937 to make way for his military parades. A long walk up Otto Suhr Allee past very indifferent 1960s building brought me to a more fascinating monstrosity, Charlottenburg's Rathaus - still very much in use, so you can wander the vast corridors and the library with the rest of the area's inhabitants. This colossal pile, built by Heinrich Reinhardt and Georg Süßenguth between 1899 and 1905, shows all too clearly what the belle epoque meant to Prussia. But I do like some of the bas reliefs, and the ironwork above the left entrance is impressive.

It makes Schloss Charlottenburg, albeit heavily restored after 1945, seem all the more elegant. I've been here before, to see the Caspar David Friedrichs as well as Nefertiti when she was housed in one of the smaller museums to the south, but I wanted to compare and contrast late 17th-early 18th century Charlottenburg in spring with mid-17th-century Versailles in winter (would have gone to Potsdam, into which Frederick the Great channelled his energies, had there been more time - that I have yet to see). The south facade includes gilt railings to match Versailles (first shot)

and handsome trees

though the space before it can't compare to Versailles. Toyed with the original plan of going round Berggruen's collection of Picassos and Klees, now housed across the Spandauer Damm, but lunch called, so I stopped at the cafe of the Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg, with its intriguing-looking collection of fantastic art from Piranesi and Goya through to Magritte and Dubuffet.

The weather was now overcast but fair, so the Schlossgarten needed exploring.

There's an intriguing mausoleum, built to a neoclassical design by Gentz as a tomb for Queen Luise between 1810 and 1812, extended by the great Schinkel after the death of Friedrich Wilhelm III - that's his effigy below; Luise's is a finer work of art, but by that stage I realised I wasn't supposed to be photographing.

Presumably further touches are part of the 1890–91 extension to accommodate the graves of Wilhelm I and his wife Augusta. At any rate, it's a hotchpotch of styles, but not without grace in some of the details.

There was just time for a quick wander of the park. Beyond the formal gardens - which I'm delighted to see were indeed inspired by Le Notre's Versailles - the looser English style takes over; in fact the whole park looked like this after 1787, but following war damage the baroque portions were restored. At any rate the lakes tie in well with the distant Belvedere

and the palace proper looks handsome across the waters.

I suppose I should have followed what my guidebook described as the 'beauty and the beast' itinerary and gone to see the memorial on the site of Plötzensee, the slaughterhouse of political prisoners between 1933 and 1945. But time was up, so I took a brief detour along the Spree, with willows and cherry trees framing enormous factory chimneys, past a functional newish Russian orthodox church

and a monumental piece of wall-art

back to the Rathaus, Richard Wagner-Platz

and the U-bahn back. There was just time before taking the train to the airport to pay homage to another grim memorial, this time opposite the hotel, to Stauffenberg and the members of the German resistance who tried to overthrow Hitler in the July plot of 1944.

It's inside the yard of the Bendlerblock, former Nazi army headquarters, where they've also erected the statue of a defiant, chained naked man, worthier than the flatulent inscription on the ground in front.

I'm guessing that even this building had to be reconstructed after 1945. It's astonishing to see a photograph of Scharoun's Philharmonie, newly constructed in 1964, surrounded by open space and only a handful of semi-ruined edifices. Couldn't find this image on the web, nor on the Philharmonie's website - for which I sought permission in reproductions below - so will have to hope this poor copy of my postcard will suffice.

I didn't have time to see the museum within the Bendlerblock, but it's worth quoting inscription on the banner which is one of the exhibits, highlighting Pastor Martin Niemöller's wise words:

When the Nazis came for the Communists, I said nothing, for I was not a Communist. When they locked up the Social Democrats, I said nothing, for I was no Social Democrat. When they came for the trade unionists, I said nothing, for I was not a trade unionist. When they came for the Jews, I said nothing, because I was not a Jew. When they came for me, there was no-one left to protest.

Now - he grandly proclaims - go away and read Hans Fallada's Alone in Berlin, and don't think of taking a jolly jaunt to Berlin until you've finished it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)