Showing posts with label St John Passion. Show all posts

Showing posts with label St John Passion. Show all posts

Friday, 20 March 2020

Four last happenings

By 'last', I mean 'for now' - the big shutdown happened, on the 'advice' but not the command of a weak government, on Monday afternoon - and under 'happenings', I include two concerts and two operas. At three of the events there was a decent distance between audience members (because so many didn't come), and at all four the astonishing phenomenon of hardly any coughing or fidgeting. A background of intense silence makes so much difference to a live performance: it really is the ideal of Britten's 'magic triangle' (composer, performers, spectators).

Such was very noticeably the case with Masaaki Suzuki and his Bach Collegium Japan giving a heart-piercing and unflinchingly dramatic performance of Bach's St John Passion at the Barbican on Tuesday 10 March. I've written about the concert on The Arts Desk (likewise the ENO Marriage of Figaro on Saturday evening and the stunning LSO concert on Sunday, a searing farewell as it turned out, which is why the lion's share of this article will be devoted to the new opera already covered on TAD). Images up top and when we come to Denis & Katya by Clive Barda.

What I haven't mentioned was the splendid lunch some time back now hosted by the concert manager of Masaaki and his equally delightful (and talented) son Masato, Hazard Chase's James Brown*, in a very pleasant, intimate room of 2 Brydges Place. I went not to be wooed, but because I already respect Suzuki senior so completely and wanted to talk Bach with him - that we did, and so much else besides. Pictured above clockwise from 7 o'clock are James, Moegi Takahashi of BCJ, my good friend of a fellow writer Nahoko Gotoh, James's hyper-efficient and engaged daughter Damaris Brown, who's one of the best PRs, Masato, Martin Cullingford of Gramophone, Masaaki, Roderick Thomson also of Hazard Chase and myself.

Had I not gone, I wouldn't have learnt about the extraordinary cantatas-plus lunchtime event Masaaki was giving with superb Royal Academy of Music students the following afternoon, nor that Masato had taken up the (unadvertised) conductor-harpsichordist's place in a Milton Court concert that evening as part of the Barbican's Bach weekend (not a fan of Benjamin Appl's, and that seeming prejudice was only fed by the event, but MS's part in it was beyond reproach. Both events reviewed here).

Bach-crazy as I always am especially after events like that St John, I was doubly delighted to be able to turn to the new BCJ recording of the St Matthew Passion - perfect in (eco-friendly) presentation and a similarly direct interpretation. Perhaps I should return to it at a closer-to-Easter point when I have time to listen more carefully, but it will certainly have a place of honour on the shelves alongside Gardiner and, yes, Klemperer (for the opposite pole, which is fine if the intensity is there). Another passion-play of sounds took place in the same venue the night before the shut-down: an LSO programme which was already impressive on paper, of Vaughan Williams' Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and bludgeoning/desolate Sixth Symphony separated by another deep masterpiece, Britten's Violin Concerto. No praise could be too high for the performers; for review link, see above.

Having been spellbound by Philip Venables' opera 4:48 Psychosis, a powerful setting of Sarah Kane's amazing play, I was keen to see his latest work, premiered and toured (for a bit, before the ban set in) by the always enterprising Music Theatre Wales. Denis & Katya came to the Southbank's Purcell Room for two nights, and I went to see it with my excellent colleague Alexandra Coghlan (Stephen Walsh had already covered its Welsh opening for The Arts Desk).

Well, Venables, this time in conjunction with a layered text from Ted Huffman, has done it again. Within the 70 minutes of Denis & Katya we never meet the two Russian teenagers who barricaded themselves in a summer cabin, shot at the TV set, a police van and even the visiting mother of one of them, all the while broadcasting their antics on the video app Periscope to the damaging responses of online watchers. With his more lyrical episodes, Venables makes one's heart ache for the waste of life at the end of it, mired in the unknown: did the 15-year-olds kill each other, or were they killed by the police (such a possibility in Russia, alas)?

There are only two singers, Emily Edmonds and Johnny Herford, who set up the action with a spoken prologue and then take on, singly or together, the roles of teacher, friend, neighbour and others in variously treated words (Russian included). Four cellists from the London Sinfonietta at both sides of the acting space add their propulsion to timed beeps on a video conversation about a programme on the subject, a kind of rondo theme to begin with. New expressive kicks come with the pacing round of a medic, and finally the deliberate lack of any film footage is broken with a film of a train leaving the station at Strugi Krasnye, where the catastrophe took place. The later stages are formed by a kind of passacaglia which gets twisted by tonal descents and a grim plunge (oddly parallel to the terrifying final descent of Sean Shibe's electric guitar in Georges Lentz's Ingwe), just as the train journey takes us into darkening woods.

So the structure is as sure in effect as the substance. This is another utterly gripping music-theatre piece from Venables which is here to stay, pity and terror held in perfect counterpoise. There was abundant laugh-out-loud wit in Joe Hill-Gibbins' staging of Figaro, which I'm so glad reached its one and only performance on Saturday night, but less of the necessary depth in the later stages. Visually, it was spare, but a gift to the photographer, so in addition to the photos which punctuated the review, I've included a further gallery of Marc Brenner's splendid work for ENO - head over to The Arts Desk for the cast.

In one last burst of careful indulgence, if that's not an oxymoron, I was totally buoyed up by a fifth spectacle, of the Titian poesie at the National Gallery on its last day before closing for the foreseeable future; but that's for another blog entry. UPDATE: I ought to add before I do the full works that the Gallery was mostly deserted, but the Titian exhibition room was fuller than I'd anticipated - though it was still possible to keep 2 metres away from everyone else. Empty West End freaked me out and I won't be cycling into town again for the foreseeable future.

*Update: I am so shocked and saddened to hear that the management agency has just gone into voluntary liquidation. I know that James and his team were honourable people; I don't know the circumstances, but the current horror must have everything to do with it.

Thursday, 5 April 2018

Bach and Dante over Easter

The Bach cantata pilgrimage with Rilling and company came to a halt over Lent, for obvious reasons. And since the only Palm Sunday cantata, BWV 182, was among the last I reached in my 2013 attempt to make a whole year of cantatas, Easter weekend marked the pick-up point. First, though, an essential Passion for Good Friday, since this year I didn't get to hear one live (the nearest I came was the unforgettable Lucerne staging of Schumann's Scenes from Faust). I have the Britten set of the St John on LP, unheard until now, with its bold reproduction of Graham Sutherland's Northampton Crucifixion on the cover, and it proved a very moving listening experience.

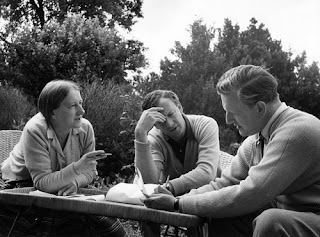

Having started with another boxed set I picked up recently in a quest to try and take unfashionable large-scale Bach seriously, Karajan's St Matthew Passion, and given up when faced with the sludge and the dim sound - back that goes to another charity shop - Britten's is a whole new world of biting passion and inscaped sadness. It's sung in English, with Peter Pears having worked on the recitatives and Imogen Holst collaborating on the rest; Colin Matthews writes briefly but eloquently on the changes in an essential booklet note. And I've been reading Imogen H on Britten and Byrd recently; what a superb clarifier she was (pictured below with Britten and Pears in the Red House garden).

Pears's burning delivery - the famous setting of Peter's weeping is as searing as any - makes it work. And there's plenty of thrust in the meaning from the Wandsworth School Boys' Choir - really, no extra voices? - and the superb soloists. John Shirley-Quirk helps realise Britten's special spirituality in the last bass aria with chorale, and Alfreda Hodgson is peerless in both Parts, much abetted by the English Chamber Orchestra oboes in No. 11. A great mezzo, easily the equal of Janet Baker and yet so overlooked by comparison.

Later I turned to another LP box I picked up recently, Britten's 'new concert version' of Purcell's music for The Fairy Queen, in which Hodgson sings Mopsa to Pears's Corydon (no all-male bad camp here, then, but plenty of esprit). Again, the stylishness and engagement leap out over a distance of 45 years, and I like what Britten does with the messy hybrid better than any other version. I've now ordered up his Schumann Faust-Szenen with Fischer-Dieskau as a third LP set to make a handsome trilogy.

Easter Day, Monday and Tuesday brought with them new cantatas to hear, so finally it was back to Rilling. 'Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret,' BWV 31, was composed by the 30-year old Bach for Weimar - the size of it suggests the original venue as not the court chapel but the main parish church known as the Herderkirche where we were lucky to attend an Easter Sunday service back in 2015, looking on the splendid Cranach altarpiece -

and probably reused in Leipzig. Gardiner suggests a parallel between the five-part chorus and the Gloria of the B minor Mass, down to the slowing of tempo and rest for the brass in the middle. It's exactly what one would expect for a 'Christ is risen' Cantata, though the ensuing recits are perhaps more striking in their word-painting than the bravura arias. There's a sublime trumpet descant to the final chorale.

Our Easter Sunday anthem this year, by the way, was Hadley's 'My beloved spake,' which we all used to love in the choir of All Saints Banstead - I realise it also enable me to recite this bit of the Song of Solomon - and which was sung on Sunday by the choir of St Paul's Cathedral. So we went there through the drear and heard the music only from a great distance, among masses of tourists. Still, Hadley's juicy harmonic shifts and two big blazes made their mark. I'm hoping close friends Juliette and Rory will choose it for their wedding this summer.

Most fascinating on the Bach front is the extreme contrast between the Easter Day jubilation and the inwardness of 'Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden,' BWV 6, composed for 1725's Easter Monday in Leipzig. The comparison here in the opening chorus is even more marked, with the bittersweet genius of 'Ruht wohl' at the end of the St John Passion, C minor key and sarabande movement included.

How wonderful the harmonies of the two oboes and oboe da caccia and the power of the chorus in Rilling's superlative performance; likewise the oboe da caccia's solo in counterpoint with mezzo Carolyn Watkinson, a singer I always liked and who appears in the Rilling Bach cantatas for the first time, and the piccolo cello against Edith Wiens (another unexpected name in the set) singing the central chorale. Profound music throughout in a great performance.

Gardiner is a thoughtful commentator again; he compares the contrast between the absence of Christ in a light-diminished world and a holding on to Word and sacrament, a contrast between dark and bright, with Caravaggio's first representation of the Supper at Emmaus, pictured above; it made me look up the second, where Christ has a beard.

Still, although it's less pertinent here (daylight is preferred to the night setting), Titian's representation, often overlooked in the Louvre because it hangs opposite Leonardo's Mona Lisa and currently in the stunning Charles I exhibition at the Royal Academy, is the one closest to my heart. Such gorgeous coloured silks, such an amazing composition.

Easter Tuesday's cantata is a little satyr-play by comparison with the Big Ones; it seems that a Telemann opening chorus was added, probably in performances after Bach's death. 'Ich lebe, mein Herze, zu deinem Ergötzen,' BWV 145, putatively reworks secular numbers lost to us. It dances its nine-minute way in a delicious opening duet with solo violin and a tenor aria with trumpet solo. A concert of all three cantatas would be as good a demonstration as any of Bach's phenomenal emotional range.

Dante's encyclopaedic frame of reference, in the meantime, continues to stun. Frail follower that I am, I missed the climactic Warburg class on Purgatorio, in which I'm told Dr Alessandro Scafi read Dante's meeting with Beatrice in the Garden of Eden with special tenderness; I'd only just back from Lucerne last Monday, and the extra half hour I'd promised the Opera in Depth students so that we could see the second and third acts of From the House of the Dead in Chéreau's production ran over; a furious pedal from Paddington to Bloomsbury would still have made me miss at least ten minutes of the class.

Anyway I shall reach the top of Purgatory Mountain under my own steam, and meanwhile I've had time to reflect on what my dual-language Dante edition calls 'the great expositions of doctrine at the centre of the Purgatorio'. That therefore means at the centre of the entire Divina Commedia. They appear in Cantos 15-18, and in our first class on the second instalment of the mighty work, Dr. Scafi and Professor Took chose three key passges from two of these Cantos. I'm going to gloze superficially in order, starting most skimmingly with the sharing of heavenly goods, which Dante adapts from Gregory the Great. Earthly ones, according to Dante's Virgil, cannot be shared without a lessening for each sharer; our democratic societies with their libraries, museums and hospitals, albeit under threat, would deny that, as translator Robert Durling points out.

Nevertheless the sharing in Purgatory which began in Canto 2 with the communal hymn in the boat bearing Dante's beloved composer Casella and others is one of the loveliest things about this second book after the total solipsism of the characters in hell. The language strikes me as especially beautiful in these central Cantos, so I'm going to quote at well with Durling's literal translation to follow.

...per quanti si dice più li 'nostro',

tanto possiede più di ben ciascuno,

e più di caritate arde in quel chiostro.

For the more say 'our' up there, the more good each one possesses, and the more charity burns in that cloister (15, 55-7).

Quello infinito e ineffabil Bene

che la su è, così corre ad amore

com' a lucido corpo raggio vène.

That infinite and ineffable Good which is up there runs to love just as a ray comes to a shining body. (15, 67-9).

E quanta gente più là sù s'intende.

piu v'è da bene amare, e piu si v'ama,

e come specchio l'uno a l'altra rende.

And the more people bend toward each other up there, the more there is to love well and the more love there is, and, like a mirror, each reflects it to the other. (15, 73-5)

Well, we can at least aspire to that down here, can't we? 'We must love one another and die'.

By the way, I'm typing out the Italian in the hope that I can memorise more here, as I have of three-line segments of the Inferno. I don't really know where to start or end in Marco Lombardo's explanation of the relationship between fate/the stars and free will in Canto 16 (the soul trying to cleanse himself in the murk is illustrated by Doré above). But I'll try to keep it down. This is the beginning of Marco's exposition to Dante.

Alto sospir, che duolo strinse in 'uhi!'

mise fuor prima; e poi cominciò: 'Frate,

lo mondo è cieco, e tu vien ben da lui.

Voi che vivete ogne cagion recate

pur suso al cielo, pur come se tutto

movesse seco di necessitate.

Se così fosse, in voi fura distutto

libero arbitrio, e non fora giustizia

per ben letizia, e per male aver lutto.

A deep sigh, which sorrow dragged out into 'uhi!', he uttered first, and then began: 'Brother, the world is blind, and you surely come from there. You who are alive still refer every cause up to the heavens, just as if they moved everything with them by necessity. If that were so, free choice would be destroyed in you, and it would not be just to have joy for good and mourning for evil. (16, 64-72)

'Lume v'è dato a bene e a malizia,' 'a light is given you to know good and evil,' Marco continues, tracing the origins with a lovely image which follows the feminine gender of 'anima',

Esce di mano a lui che la vagheggia

prima che sia, a guisa di fanciulla

che piangendo e ridendo pargoleggia,

l'anima semplicetta, che sa nulla,

salvo che, mosso da lieto fattore,

volontier torna a ciò che la trastulla.

Di picciol bene in pria sente sapore;

quivi s'inganna, e dietro ad esso corre

se guida o fren non torce suo amore.

From the hand of him who desires it before it exists, like a little girl who weeps and laughs childishly, the simple little soul comes forth, knowing nothing except that, set in motion by a happy Maker, it gladly turns to what amuses it. Of some lesser good it first tastes the flavour; there it is deceived and runs after it, if a guide or rein does not turn away its love. (16, 85-93)

This is a fine amendment of Augustine's concept of original sin: Dante is telling us that human nature as such is not corrupt, but simply makes bad choices (by the way, God, please send me a Virgil who looks like Hippolyte Flandrin's above). No wonder Dante wanted to reinforce and expand on Marco's words with Virgil's in Cantos 17 and 18. Although the language is drier, more theoretical, I love these lines:

'Né creator né creatura mai,'

comincio el, 'figliuol, fu sanza amore,

o naturale o d'animo, e tu 'l sai.

Lo natural è sempre sanza errore,

ma l'altro puote errar per male obietto

o per troppo o per poco di vigore.

'Neither Creator nor creature ever,' he began, 'son, has been without love, whether natural or of the mind, and this you know. Natural love is always unerring, but the other can err with an evil object or with too much or too little vigour. (17, 91-6).

More on love natural and elective, with further subdivisions, is to be found in the continuation of Virgil's observations in Canto 19, but this is probably more than enough to try and digest for now. Mighty Dante - intellect and poetry perfectly conjoined to make independent thought that is anything but simplistically moralising.

Saturday, 15 April 2017

Easter interstitial

So here we are still in London, and not in Norfolk as planned - J has a cold. No matter; it's good to be at home after a week of rushing around Europe. And I always love the reflective period before Easter itself. Very happy, in looking for images to accompany my review of the Dvořák Requiem on Thursday, to have rediscovered a masterpiece which stunned me when we spent Christmas in Prague back in 1990, the altarpiece from the Vyšší Brod Monastery. My Czech friend Jan reminded me of it in sending a postcard of the above, taken from the depiction of Christ in the garden of Gethsemane.

The mourners at the cross are expressive, too.

We spent an hour and a half of contemplation on that theme yesterday afternoon in Westminster Abbey. Our dear Spanish friend María Jesús wanted to meet up, and though I fear we let her in for a longer ritual than any of us had expected, I hope she found it a treat. Anyway, we did get to chat over tea afterwards. That's Giotto's great crucifixion on the order of service cover, of course.

Certainly it was surprising to find that the congregation queueing and then packed in around the central tower didn't consist of casual tourists, but a plethora of believers (among which I do not count myself, however much I take from the Passion narrative). Indeed, the number of folk wanting to venerate the cross meant the whole service took much longer than expected (the Communion was more streamlined, with priests serving both aisles). Never come across this business before - nor has J, with his Catholic upbringing - and found it all a bit mumbo-jumbo-y, but then I guess so are the rituals which I've grown up with since I was a choirboy, and I say the Creed without a second thought.

The order of service cannily embraced a diversity of styles and nations - plainsong, Lutheran and Anglican hymns, and composers Spanish (Victoria - the central St John Passion, in which 'composition' is not much present, but it was splendidly delivered by two tenors, bass and choir), Italian (Lotti) and Austrian (Bruckner). Much as I love anthems like Locus iste, which we sang at Stephen Johnson's and Kate Jones's wedding, I blush to say I didn't know the latter's Christus factus est, and it's a masterpiece, covering so much of the composer's mature style in such a short span. The Westminster Abbey Choir sang it with magnificent fervour in the climaxes. Here it is performed by, of all things, a Japanese high school choir, and very well, though you need to look away from the gurning individual among the boy-men...

Some of the details in John 18 and 19 took me by surprise. Hadn't realised, for instance, that Pontius Pilate did what he could to avert the sacrifice. And this I love: 'When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother: "Woman, here is your son." Then he said to the disciple: "Here is your mother". And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.'

On which note, there's a marvellous poem on the Stabat Mater theme by Joseph Brodsky in his Nature morte. I came across it as the third of Estonian-based, Ukrainian-born composer Galina Grigorjeva's settings gathered together under the same name. It was high time I listened to the disc by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir which had been sitting here for too long. Grigorjeva calls the poem 'Who are you,' and here it is.

Mary now speaks to Christ:

'Are you my son? - or God?

You are nailed to the cross.

Where lies my homeward road?

'Can I pass through my gate

not having understood:

Are you dead? - or alive?

Are you my son? - or God?'

Christ speaks to her in turn:

'Whether dead or alive,

woman, it's all the same -

son or God, I am thine.'

Alas, this setting isn't available on YouTube, but there's a marvellous film there which includes the second setting, 'The Butterfly,' remarkable especially for capturing Grigorjeva's spirit as she talks to the choir about it. I'm waiting for her score of the new and remarkable Vespers I heard premiered in the Niguliste (Church-)Museum last week by the stupendous Vox Clamantis choir. She sent me a very polite email saying she couldn't send it or hand it over just yet because she'd noticed some mistakes. A composer of obvious and rare integrity.

Finally, a few more seasonal flora shots from the cycle home after the service yesterday - tulips in the meadow arrangement in front of Clarence House

and wisteria backed by white lilac - both out already - in Launceston Place, the magical street which runs parallel to Gloucester Road.

Saturday, 30 March 2013

Back among the palms

Signing in here with Easter greetings, to catch up with last Sunday's Bach cantata - the first for weeks, of course, after the Lenten near-silence - and to explain briefly where I've been: namely in Sicily, four glorious days in Palermo, a city of whose riches I had little inkling, and three roving in the Madonie mountains. Hard to say which was more breathtaking, the civic art or the country sweep.

What's for sure is that the Normans brought to Palermo an Arabic-infused art that no other Italian city can boast. In the Cappella Palatina of the original castle, in the competitive monumentalism of Monreale and in the more intimate beauties of the Martorana church back in the city are mosaics to rival, in my view to surpass, Ravenna. Oddly there are no crucifixion scenes in the stunning chapel, but of many detailed 'pictures' Christ's entry into Jerusalem above stands out. Below Jesus, Peter and the white ass are four children throwing fronds and laying their own clothes before him. The disciples follow behind, while three bearded priests stand at the gate with townspeople of Jerusalem.

We may not be there in Palermo for the wild celebrations of Easter - our last glimpse of Holy Week was trailing behind black-hooded crossbearers and a funereal band on our way to the airport - but we did catch Palm Sunday, which everywhere in Italy other than the Vatican is a matter of olive branches rather than palms.

This processional took place in the former convent adjoining Santa Maria degli Angeli (otherwise La Gancia). The choir processed chanting 'Hosanna, figlio di David, Hosanna, redentor' to the accompaniment of tambourines. Branches raised aloft

were then sprinkled from the priest's thurible. Most of the folk seemed more concerned to get this done and be off to the bosom of the family rather than to stay for the service, which was prefaced with a processional to the peal of bells. This 23-second film is no masterpiece, but hopefully it captures a sliver of atmosphere.

We were off too, touristically eager to catch the next processional in my favourite church of the Kalsa district where we were staying, the Norman Magiana - chiefly because only the cloisters and chapel had been accessible on our first visit, and now the doors of the wonderful church were open for a service too. Again, the majority of celebrants are heading away following the little ritual.

More on all this over the weeks to come (prepare yourself for Sicilimania). The Bach cantata for the day I chose (catching up, not too appropriately, on Good Friday) was 'Himmelskönig, sei wilkommen', BWV 182, written in 1714 when Palm Sunday coincided with the Feast of the Annunciation. The lovely sound of the recorder duets with solo violin against pizzicati as the opening Sinfonia begins; it's a wonderful moment when the collective strings swell their way into the picture.

Palm Sunday celebration (Giotto's peerless Padua fresco depiction above) continues in the vivacious crowd welcome and the bass's robust if unremarkable aria. Soulful preparation for the suffering to come follows in the next pair of solos: the alto's at the heart of it all, with the solo recorder's enfolding descents even more remarkable than the vocal line, and the tenor's determination to follow the stumbling Christ on his Calvary route caught in a continuo maze that several times loses its orientation.

Then it's back to choral celebration with a fantasia on a chorale and an almost ecstatic final dance. Gardiner (my listening choice, as often): 'it needs the poise of a trapeze artist with the agility of a madrigalian gymnast - and is altogether captivating'. Here's Harnoncourt's recording.

Good Friday was our first day back, and much as I'd have loved a day at home before gadding off again, the soloists and ensemble of a St John Passion at the Barbican proved too strong a lure. Almost too moved to write coherently after it, I struggled to put the experience into words here for The Arts Desk. I'm sending off my tenner to support the recording they still need to raise £5,000 for: such a line-up only happens once in a blue moon. Here, finally, is Lotto's sumptuous take on the Crucifixion, still a church altarpiece in a very out-of-the-way and extremely friendly village of the Marche, Monte San Giusto, which we caught on one of our May walking trips in the Sibillini.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)