Last Thursday I'd spent all morning in a mood of heartsick distractedness, following the latest developments in Ukraine. The plan in our seventh class was to move on to Kodály's Háry János. But I was in no mood for light-heartedness, and at the risk of depriving students of their 'safe space', I turned explicitly to music that somehow reflected the grief and fury we all feel about Putler's senseless invasion.

The biggest work to fit the bill was Kodály's Psalmus Hungaricus, a work I've never heard in the concert hall. And why on earth not? It's a masterpiece, setting a gloss on King David's Psalm 55, "Hear my prayer" (that same text which inspired Purcell's radically chromatic anthem and Mendelssohn's famous anthem for treble and choir, in which I was lucky enough to sing the solo part before my voice broke). The image above is of King David painted on an egg by my dear but long since unheard-from St Petersburg friend Natasha Romashova, who moved to Sacramento some years ago as the wife of a Russian dentist; her wonderful mother Sima joined her later.

The Hungarian version is by the 16th century poet, preacher, and translator Mihály Vég, written at a time when Hungary was under Turkish occupation. The 1923 Budapest concert in which Kodály's work had its premiere was supposed to be a 50th anniversary celebration of the unification of Buda, Pest and Óbuda, so this Biblically derived, plaintive offering must have seemed odd, even though it moves finally to thanksgiving. The wails, the powerful climaxes and above all the transcendent moment when Kodály anticipates Martinů in an extraordinarily levitational passage are all perfectly placed.

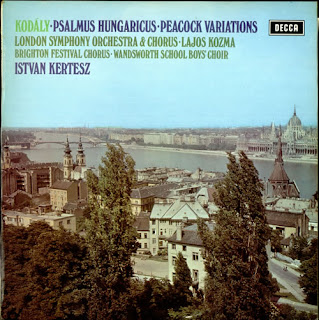

I listened first of all to István Kertész's splendid Decca recording with an excellent soloist, Lajos Kozma, and a not quite incisive enough Brighton Festival Chorus. On YouTube there's a film of Péter Eötvös conducting the International Chorakademie Lübeck and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra with tenor István Kovácsházi (not as expressive as Kozma, but the choir is better). but that performance also features in one of those labours of love in which the poster has added the score. Especially useful since you can also read the text in English translation.

Leading up to this, what I'd already planned made sense last Thursday. First. the three soldiers' songs Bartók added in 1918 to an earlier set. Finding these evocative 1928 performances on YouTube was a revelation. I'm delighted to have got hold of a copy of the long-deleted Pearl CD. That's Bartók and his only close friend Kodály' in 1912 on the cover.

The Hungarian-Greek contralto Mária Basilides is so fine-tuned to Bartók's piano-playing in the first four (one of the original eight is omitted); then at 5m05s comes the tenor Ferenc Székelyhidy - a great voice, a fine artist, one of so many Hungarian musicians of whom I knew nothing until I started this course (and there's not a lot out there). I'll preface it with the texts of the soldiers' songs:

Recruiting Song

They are filling the great forest road

Taking away the Transylvanian soldiers,

Taking the unfortunate ones,

Poor Székler young men.

They take them away to that place

Where the road is red with blood,

From the men whom the bullet, the lance,

The sharp sword have cut.

Soldier's Farewell

My work has always been the spring plowing,

Cutting grasses in fields and gardens;

Now my ox is in his place, my horse is saddled,

My whip ready, the halter in my hands.

The day has come when I must leave,

To depart from my home, my country, with a heavy heart,

To take leave of my parents in tears,

To leave my dear wife alone.

Soldier's Spring Song

Snow is melting, oh my pretty little angel, spring is coming.

How I wish to be a rosebud in your garden!

But I can’t be a rose; Franz Josef wilts me.

In the big three-storey Viennese barracks.

A reminder again that the Soldiers' Songs begin at 5m05s, though it's worthing hearing the full seven.

From the same recording sessions I took Székelyhidy and Bartók in Kodály's powerful arrangement of 'Rákóczi's Lament', a memorialisation of that early 18th century Hungarian warrior's unsuccessful cause. No translation here, I'm afraid; and translations generally have been a problem. So has English-language study of Hungarian music - I guess few musicologists ever get to grips with the language.

Who'd have thought we would actually comprehend the heroism of taking a stand against an overpowering enemy? But in President Zelenskyy we have it as I've never experienced in my own lifetime. Tomorrow I'm putting up a piece on The Arts Desk celebrating Russian musicians around the world in solidarity with Ukraine, and I'm doing what I can with constant posting on LinkedIn, much as I detest the site's inaction on disinformation. But I'll leave you with this speech for the ages. Zelenskyy has just made another one today to the European Parliament which was even more emotional. Slava Ukraini!