It wasn't long enough. In the end the Opera in Depth term just concluded was eaten up, by general consent, with Der Rosenkavalier, including visits by Richard Jones and Felicity Lott (Robert Carsen would have come along, too, if he hadn't had to leave for America prematurely). I would have loved to spend longer with Rimsky-Korsakov's enchanting Snow Maiden, but I hope we managed to make a very lovely whistlestop tour of its four acts (five including prologue) in half the time it takes to perform the entire opera (usually heavily cut, as it was by Opera North in a production which still managed the magic well despite its Russian sweatshop setting. I wonder what Tcherniakov will make of it in Paris. Shortly to find out).

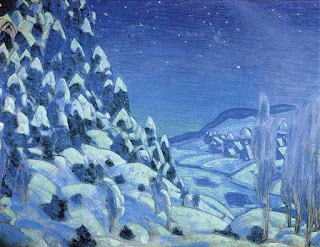

I find I can reproduce some of the greatest hits here, so let's start with the atmospheric Prelude. It's a good tone-poem evocation, like the design by the great Roerich below (his are also the other designs featured), of the stage directions by Alexander Ostrovsky, whose 'spring fairy tale' was the basis for Korsakov's first operatic masterpiece, and for which Tchaikovsky wrote equally delightful incidental music in 1873.

Beginning of spring. Midnight. Krasnaya Hill is covered in snow. To the right, bushes and a leafless birch grove; to the left, a dense forest of large pine and spruce trees, their branches bent low and covered with snow; in the distance at the foot of the hill a river is flowing; round its ice-holes and melted patches of water a fir-grove has been planted. On the far bank of the river the Berendeyev town....: palaces, houses, peasant cottages, all made of wood decorated with elaborate painted carvings; lights in the windows. A full moon covers everything in its silver light. In the distance, the sound of cocks crowing.The Wood Demon is sitting on a dried out tree-stump. The whole sky is filled with returning migratory birds. Spring Beauty, borne by cranes, swans and geese, descends to earth, surrounded by her retinue of birds.

This performance, from the great Yevgeny Svetlanov and his 'orchestra with a voice' (Gergiev) the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, is of the whole orchestral suite, including the chorus of birds without the delightful vocal parts, the quaint March of Tsar Berendey's Court (a model for Prokofiev's March in The Love for Three Oranges) and the best-known number, the Dance of the Tumblers from Act 3's summer revels.

We have to catch something of Snegurochka's very own personal magic. She's summoned by ill-matched parents Frost and Spring, and in her first aria tells them how she's attracted to the songs of shepherd-boy Lel and his fellow villagers. The first theme associated with her, heard in the first vocalised text, appears originally on the flute and I have no doubt that Prokofiev deliberately quoted it in the exposition round-off of his "Classical" Symphony's finale. After all, the symphony was composed in enchanting spring circumstances outside revolution-torn Petrograd. There's been a timely Decca release of Russian and other operatic arias and songs by the gorgeous Aida Garifullina, whose amazing presence the Opera in Depth class saw in DVDs of Graham Vick's Mariinsky War and Peace (special loan). The version with orchestra isn't on YouTube, but we're lucky to have this film of Garifullina performing the aria with piano at one of the Rosenblatt recitals. She's certainly musicality incarnate.

I have one complete recording with which I'm very happy, conducted by Fedoseyev with Irina Arkhipova doubling the roles of Spring Beauty and Lel. Such a distinctive sound, even if Lel's three songs could be subtler. The whole recording is on YouTube, and I link to it near the bottom here, but for now let's just pick out Lel's Third Song from the midsummer ritual of Act 3.

Other highlights include character-tenor Tsar Berendey's first aria with cello obbligato - I have an old 50s recording with Ivan Kozlovsky, an acquired taste and sadly not on YouTube. That leaves us nothing here of Act 2 other than Roerich's splendid design for Berendey's palace.

There are also fascinating comparisons to be made between Korsakov's and Tchaikovsky's scores. Though the former's dance is better known, Tchaikovsky's skomorokhi are more joyous still and their music touches on the liveliest numbers in Swan Lake, composed around the same time (early 1870s). There's a terrific performance from Neeme Järvi and the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, but the winner is an outlandish arrangement for the Osipov Balalaika Orchestra in the legendary 'first recording made with western equipment on Soviet soil'.

One passage can't be extracted here which Prokofiev describes very movingly in the autobiography of his youth commemorating Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908. Amongst other observations, he records his St Petersburg Conservatory professor, Nikolay Tcherepnin, saying 'When a French orchestra was rehearsing Snow Maiden in Paris (or perhaps it was Monte Carlo), the musicians were so delighted with the festive scene in the sacred wood, when Lel takes Kupava to Berendey and kisses her to the strain of a marvellous melody, that when it came time to play the melody again they suddenly put down their instruments and sang it. That was a really exciting moment'.

Our last stretch in the class was the climactic duet between Snegurochka and Mizgir, the human to whom she's finally decided to give herself - two unforgettable tunes here - her melting in the rays of the sun and the glorious hymn to Yarilo led by Lel - a tune in 11/8 time. Another Prokofiev anecdote is essential here, since Korsakov wrote two 11/8 ensembles. He's remembering a discussion of his youth with his older friend, the vet (and fellow chess player) Vasily Morolev.

In the stallion's stall he asked me. 'You mean you really don't know Rimsky-Korsakov's opera Sadko? It's a fine piece of work....In the first act there is a chorus in 11/8 time so exciting that you simply can't sit still in your seat.'

I gave a start. 'In 11/8? I know that in Snow Maiden Rimsky-Korsakov has a chorus in 11/8. and I even heard that one conductor, who simply couldn't manage to conduct the chorus, kept muttering all during the singing of it; "Rimsky-Korsakov has gone completely mad" ["Rimsky-Korsakov sovsem s uma soshel']. But when I tried it, it turned out that the phrase doesn't fit the chorus from Snow Maiden, because it comes out "completely mad"[ie with the stresses displaced].

'Wait a minute!' Morolev exclaimed excitedly. 'Maybe that phrase fits Sadko!' And he began to sing in turn 'Hail, Sadko, handsome lad' ['Goy ti Sad-Sadko, prigorii molodets'] and 'Rimsky-Korsakov has gone completely mad'

'It fits! It fits!' we shouted at the same time. And we began to sing the theme of the chorus, first with one text, then with the other [Prokofiev writes out a musical example to prove it].

No YouTube snippet of the final ensemble exists, so you can have the benefit of the entire recording. I own a good CD edition on a rare label which sounds better than this, but it will do. Zoom forward to 3'05'28 if you want the last two minutes. Listen out for the shifting chords above a fixed bass which surely gave Stravinsky the cue for the very end of The Firebird.

The only DVD we had access to in the class, not on YouTube, was the very charming and ethnographically detailed Soviet film of Ostrovsky's original play I bought from the Russian Film Council, with splendid folk music using the right kinds of voices (obviously the numbers are not Korsakov's).

The other option, if you don't mind a condensed version and you want to entertain children - or indeed, just yourself - with something rather lovely in its old-fashioned way, is a sweet Russian cartoon (with subtitles) which includes many of the musical highlights.

I ought to add by way of footnote that our previous two Opera in Depth classes had been devoted to Act 3 of Der Rosenkavalier. Apart from the usual extracts ranging far and wide, the DVD I chose to show was of Richard Jones' production from Glyndebourne. No-one has ever managed, in my experience, to make the discomfiture of Ochs pass in a flash, not to mention be funny and dark at the same time (pictured below, Lars Woldt and Tara Erraught, singers with fabulous comic instincts both, by Bill Cooper for Glyndebourne).

It soon became even more apparent that this is Jones at his meticulous best, choreographing every move with rigour, throwing out much of Hofmannsthal's detailed scenario and finding his own equivalents to match the music at every point. Had been intending to switch over to a final scene with truly great voices (Jones, Fassbaender and Popp for Carlos Kleiber or Te Kanawa, Troyanos and Blegen for Levine), but neither seemed so perceptive on the human level, so we stayed with Jones to the charming end (yes, he actually makes something warm and amusing of Mohammed's entry to retrieve - not Sophie's handkerchief but the wrap of the mistress with whom he's besotted).

Next term we move on to two lacerating studies of jealousy, close in time but musically poles apart - Verdi's Otello (Francesco Tamagno pictured above) and Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. Ten Mondays 2.30pm to 4.30pm starting 24 April at the Frontline Club. Leave me a message here if you're interested in joining with your email: I won't publish it but I promise to reply.

.JPG)