That's Nikita, tenor Nicky Spence's character in Krzysztof Warlikowski's burningly intense production of

Janáček's From the House of the Dead at the Royal Opera. He's seen above in Clive Barda's image harming the basketball-playing 'Eagle' of Salim Sai. But in reality Nicky is the loveliest of men, pure communicative energy with just the right degree of thoughtfulness.

He came along to my Opera in Depth class at the Frontline Club, where we're currently studying

From the House of the Dead, on the recommendation of the opera's predictably brilliant conductor Mark Wigglesworth. A regular visitor, Mark has been unable to return this term because he's been preoccupied with three works - the Janáček, a Spanish run of Jake Heggie's

Dead Man Walking followed by the

BBC Symphony Orchestra's concert performance - which I missed, dammit, because I was in Berlin that night hearing another conducting hero, Neeme Järvi, in Rudolf Tobias's massive oratorio

Des Jona Sendung (

Jonah's Mission) - and Verdi's

La forza del destino in his debut at Dresden's Semperoper. He promises to come back in the autumn, by which time his book on conducting will have been published (can't wait for that).

Anyone that Mark recommends to come and speak is going to be a true

Mensch like himself, that rare figure who goes beyond just being nice - there are more of that sort in the opera business than you might expect - and is an active force for the good. I include in that gender-unspecific category soprano

Tamara Wilson, the great Leonora in MW's

ENO Verdi Forza whose appearance as Wagner's

Brünnhilde in the final scene of

Die Walküre at the Proms Mark generously ascribes to my suggestion - let's hope eventually she performs the entire role for him, by which time Nicky may be up to Siegmund or even Siegfried - as well as our other soprano visitors Sue Bullock (an unreserved admirer of Nicky's work), Anne Evans and Felicity Lott ( I reserve their damehoods because SB should be one too).

Which is a long preamble to saying that Nicky (pictured above, and below with me looking inexplicably quizzical, at the Frontline by David Thompson) and I, from my perspective, got on instantly over the Frontline's fish and chips (best in London?) 'Grounded' is the word I and several students have used - he knows his worth but he's not arrogant in the slightest (that's usually born of insecurity). He learnt the hard way, promised 'fame in a night' with a Universal Classics/Decca record deal where he recorded 'stuff for grannies' and sang for the Queen (etc, etc - I can't say I remember this), but was pulled up short by a devastating review from Rupert Christiansen which sent him straight back to music college to get his voice properly in order over years. So we critics can sometimes have our uses, and Nicky acknowledged that RC, however harsh, had done him a favour.

It was serendipity that Nicky (pictured by Clive Barda above in rehearsal with Graham Clark - the oldest and the youngest members of the Dead House cast together, as Nicky remarked when putting it up on social media) came to be working with Mark again, having sung in two of the four triumphs of Wigglesworth's all-too-short regency, the

William Kentridge-directed Lulu (which I saw three times) and the

revival of Jenůfa in which he was a memorable Števa; MW was only called in to the Dead House after maverick Teodor Currentzis had pulled out. Nicky knows he gets a level of support and enlightenment from MW not common in conductors. He spoke interestingly about the slow evolution of Warlikowski's vision, in which space was given within the parameters of given scenes that actually worked rather than ending up an incoherent mess (he does a good Warlikowski impersonation).

I need to listen over to the private recording of our two hours in the class for chapter and verse, but suffice it to say for now that Nicky is on the right path towards the bigger Wagner roles. Next step is Loge for Philippe Jordan in Paris - as he pointed out over lunch, listening back to earlier singers of the role, he found them more Helden/lyrical, like Windgassen, than the character tenor we tend to get today - and Strauss's Herod is good semi-Heldentenor role for him, too.

We played excerpts from his superlative Strauss Lieder disc, last in the excellent Hyperion series. Roger Vignoles lured him in with the famous '

Cäcilie', but didn't tell him the rest would be bits and pieces left untouched by previous singers. Yet we agreed that there were some absolute gems here, and both, independently, decided that 'Die Ulme zu Hirsau' was the other track to play. It has a huge range as it depicts the tree growing through a ruined monastery - the piano's ripples are a precursor to Daphne's transformation in the much later opera - and after a heart-leaping modulation quotes Luther's 'Ein feste Burg' for Uhland's lines about 'another such tree at Wittenberg'.

And we finished with the second part of Pavel Haas's

Fata Morgana song cycle for voice and piano quintet, an even bigger sing. This connected us to Janáček, since Haas was his pupil and composed the cycle in 1923, the year after his great master had written

The Wandering Madman in typically quirky style for chorus to a text by the same poet, Rabindranath Tagore.

The sad connection with

From the House of the Dead is that after Janáček's death mercifully prevented him from seeing the horrors of the Second World War, Haas's Jewish background landed him in Terezin (Theresienstadt), where he composed the desperately poignant 'Four Songs on Chinese Poetry' about exile and separation shortly before he was sent to Auschwitz and the gas chambers there in 1944. I had no idea until I just read it that the great Czech conductor Karel Ančerl was there too, and survived the experience, unlike his wife and child. He recounted that he and Haas were lined up before Mengele, who was about to send Ančerl to his death, but when Haas began to cough, chose him instead. The horror of it.

So, tomorrow, back to study of Janáček's last masterpiece, his most startling and orchestrally outlandish. Not sure how I'll get a grip on it.* I wanted to buy the orchestral score, but Universal wants over 400 euros for making one up, so I'll have to look on line instead. Next term's operas are (coincidentally) 'ill met by moonlight' - Strauss's

Salome and Britten's

A Midsummer Night's Dream, the Carsen production of which I saw again with great pleasure on Wednesday (pictured above by Robert Workman, a plus against the definite minus of the

shoddy, poorly directed Traviata which has just opened - my review has surely squandered the goodwill built up with ENO by

ecstatic praise of the Iolanthe, but one shouldn't mince words where incompetence is concerned. Disagreeing with the approach is something else altogether).

If you're interested in joining our summer classes, leave me a message here - I won't publish it but if you leave your email, I'll reply immediately.

*20/3 Yet I think I did - it makes much sense as units governed by searing themes, usually made up of no more than four notes, and in performance you don't notice the joins as one 'scene' segues into another.

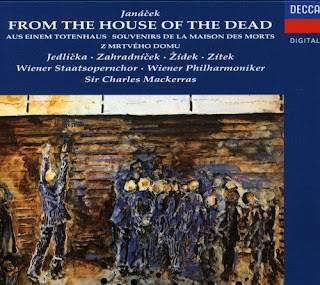

Our guide, alongside the online score, was Mackerras's electrifying recording, which can never be surpassed (we'll watch the Chéreau production conducted by Boulez next week). In fact I'd go so far as to say that given the stupendous sound - those timps and the trilling high-wire trumpet at the end of Act One! - and the playing of the Vienna Phil, which can never have gone out on more of a limb, it may be the most stunning of all opera recordings. Left us trembly yesterday afternoon.

%2BCatheine%2BAshmore.jpg)

.jpg)