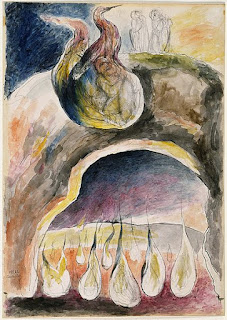

Forgive the excessive alliteration, but it seemed a neat way of conjoining this week's Dante and Bach discoveries. The latter is Richard Stokes's suggested translation for 'Leichtgesinnte Flattergeister,' the title of Cantata BWV 181. The former refers to Ulysses and Guido da Montefeltro, speaking as tongues of flame in, respectively, Cantos 26 and 27 of Inferno. The Eighth Circle, heading towards the bottom of the funnel, is reserved for 'Simple Fraud', and the eighth of its 11 bolgie contains these 'counsellors of fraud in war'. If we widen that definition to 'fraud in words', then it suits the three mini horror clowns I've rather crudely coloured in flame tones above - Gove, BoJob and J Rees-Mogg, the GoBoMo triplets, folk who use a rather silly form of cleverness to deceive the gullible, though God knows they're petty demons compared to Dante's heroic hell-dwellers.

Once again, following on the heels of the talking twigs, our artists are confounded by the fact that it's the flames that speak, not figures within; but you have to allow Blake and co their visual licence. What's said, as our reader Dr. Alessandro Scafi and interpreter of deeper meaning Prof. John Took underlined in Monday's Warburg session, is tauntingly selective and if you don't have the entire context - even this Ulysses/Odysseus narrative departs from the Greek sources, and Guido da Montefeltro is not as familiar to us as he was to those living shortly after his death - you need plenty of glosses even before the meaning can be plumbed.

Dante gives us Ulysses' last journey, but not as we know it from Homer. After leaving Circe, he does not head for Ithaca and the moving/violent homecoming of The Odyssey: 'neither the sweetness of a son, nor compassion for my old father, nor the love owed to Penelope, which should have made her glad, could conquer within me the ardour that I had to gain experience of the world and of human vices and worth' -

né dolcezza di figlio, né la pieta

del vecchio padre, né 'l debito amore

lo qual dovea Penelopè far lieta,

vince potero dentro a me l'ardore

ch'i' ebbi a divenir del mondo esperto

e de li vizi imani e del valore...

'A devenir del monde esperto' - this had been an earlier stage of what Prof. Took calls 'Dante's problematic humanity'. After the death of Beatrice, he spent time in the Florentine philosophical schools acquainting himself with Cicero, Boethius and, for him the greatest, Aristotle. His discoveries are noted in the Convivio. But this absolute enthusiasm for life-knowledge needed rethinking in the contet of his spiritual existence - 'quickened by grace and revelation' (Took) - and the Divina Commedia marks Dante's 'theological encompassing of reason'.

So did Dante see Ulysses as a dark image of his own earlier, 'recklessly self-confident' reasoning? He certainly refers to him a lot; and elsewhere he uses the idea of a physical journeying as the image of a spiritual one (the oceanic image crops up in Paradiso's Canto 2). The below Doré illustration, by the way, is for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, but it fits Ulysses' last journey towards the extreme west well.

Here Ulysses goes beyond the boundaries, marked physically by the Pillars of Hercules, and his crime is to use his tongue to persuade his old remaining company to follow him to what turns out to be extinction: 'you were made not to live like brutes, but to follow virtue and knowledge' ('fatti non foste a viver come bruti, ma per seguir virtute e canoscenza'). Is this hubris? Or, more precisely, in John Took's so-eloquent phrase, how 'the word fractures communion for pure self-interest'?

The end finally comes in the whirlwind from the high mountain surmounted by Eden; it sweeps the men to destruction.

There's fabulous drama in Guido's speech. The man of arms became a Franciscan, 'believing, so girt, to make amends; and surely my belief would have been fulfilled, had it not been for the high priest, may evil take him! who put me back into my first sins' -

Io fui uom d'arme, e poi fu cordigliero,

credendomi, sì cinto, fare ammenda;

e certo il creder mio venìa intero,

se non fosse il gran prete, a cui mal prenda!

che mi rimise ne le prime colpe...

This is Pope Boniface VIII, Dante's deadly enemy, who asked Guido's advice in subduing the Colonna family in Praeneste/Palestrina.

I love the dark humour of the black cherubim who seizes Guido's soul (depicted above by Joseph Anton Koch in a drawing in the Thorvaldsen Museum - he is also the artist below), saying, 'Perhaps you did not think I was a logician!' ('Forse tu non pensavi ch'io löico fossi!'). Then he drags Guido off to Minos, who twists his tail furiously eight times in judgment on the sinner destined for 'the thieving fire'.

Next week we descend to the very bottom to meet Judas, Brutus, Cassius - and Satan. Io tremo.

Bach's BWV 181 takes us from the threat of hell to heavenly consolation via the New Testament reading for Sexagesima Sunday, the Parable of the Sower in Luke 8.4-15. The sower in question casts seed on four types of ground which image the varying types of receptivity to Christ's word, from stony to fertile. 'Leichgesinnte Flattergeister' is unusual in beginning with a bass aria in which some have detected the pecking of the birds who gather up the seed on the worst soil.

There's a helpful connection to Dante and Milton with the appearance of Belial in the aria's central section.

It feels to me more like an operatic number by Handel, strengthening the notion of theatricality in the cantatas. The recitatives are highly expressive, and in the short tenor aria, I love Rilling's choice of vivid harpsichord, mirroring the thorns of the text, against the bassline - throbbing at 'höllischen Qual' ('hellish torment'). The second recitative turns us to comfort, and a chorus at last, bright with trumpet and a soprano/alto duet in the middle. Gardiner praises its 'madrigalian lightness', a good way of putting it. This is a short cantata, but as original as any.