So while I reached the Empyrean with Dr Scafi and Professor Took at the Warburg, and got to the end of reading Paradiso shortly afterwards, serendipitously just prior to visiting the Ravenna Festival, the one-Bach-cantata-per-Sunday scheme bit the dust again, this time on the first Sunday after Trinity. I'd already accumulated a backlog, which just got too much with so many summer weekends away.

It does seem good, though, to end on a very rich masterpiece which I also got to hear in John Eliot Gardiner's second Bach cantatas concert in the Barbican's rich Barbican weekend (alas, the only one I could make). BWV 20, 'O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort', had to be a big statement - it launched Bach's second Leipzig cycle on 11 June 1724 (thus another image of the Thomaskirche from my first acquaintance with it last December).

No-one could write about this thunderbolt of invention better or with more inside knowledge than Gardiner, and he does so in Music in the Castle of Heaven, pages 313 to 317 (I recommend you read it all, of course).

It is an astonishing piece, one that sets the tone for the whole cycle and sums up so many of the original features we will encounter - a new range of expression, the use of operatic technique to enliven the doctrinal message and wild contrasts of mood....We seem to be already in the death-throes of the Trinity season, not at its start - but then Bach's was an age that had a taste for apocalypse and the theme crops up regularly and unexpectedly.

What, in briefer terms, does Bach serve up? First a choral fantasia in the form of a French overture, starting with an astonishingly original idea and freezing us in our tracks on a diminished seventh, followed by heart-quaking fragments in a slower middle sequence. What an effect the three stammering oboes have at this point. No idea whose performance this is, but good to have the score accompanying the opening chorus on YouTube.

A tenor aria with a turbulent bass line and sorrowing strings 'piles on the agony' (Gardiner). The bass seems to shift into an almost comical light for the over-assertions of 'Gott ist gerecht', but we are back with pain and grief with the alto's tragic chromatic number. The coda, piano, for strings alone reprising what's been sung, is a subtle dramatic coup.

After this, prefaced by a hymn stanza, the preacher would have given his sermon. His the prerogative to make the transition to a very different mood, striking with the huge range of bass backed up by trumpet and strings. To my ears it outdoes Handel's 'The trumpet shall sound', but maybe familiarity has bred a certain taking-for-granted of that magnificent aria. There's a very expressive 'repent ye' alto solo, and then what struck in the Barbican concert, almost whispered throughout, as one of the most extraordinary, dramatic inventions in all the cantatas.

I have to quote JEG on this, since he clearly thinks so too:

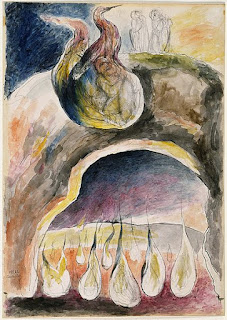

It is not very often that Bach resorts to lurid pictorialism of the Hieronymus Bosch kind; yet, in the ensuing duet delivered to the errant programme as though by Bunyanesque angels (alto and tenor), he treats us to a ghoulish cameo of 'howling and chattering teeth', of the ominous approach of the hand-drawn hearse as it clatters across the cobbled street. Successions of first inversion chords over a disjointed bass line in quavers with parallel thirds and sixths in the voice parts give way first to imitative and answering phrases, then to an anguished chromaticism evoking the bubbling stream and the drop of water denied to the parched rich man. The voices join for a final flourish. We hear the gurgling of the forbidden water and the continuo playing a last furtive snatch of the ritornello. Then, dissolve...fade out...silence. Extraordinary.

This performance isn't a patch on Gardiner's, and I've got so used to hearing top mezzos and contraltos on the Rilling set that the countertenor doesn't please me much, but it's helpful to see what Bach is doing in the score.

There is light at the end of the concluding chorale, but the overall impression is one of disruption - and total, timeless genius. I may have given up this year, but I'll be thrilled to pick up where I left off in June 2019, sticking to the 1724 sequence.

In my last post yoking Bach and Dante, I was worried that our Warburg discussions about selected cantos of Paradiso were more interesting than the poetry in question. All that changed when Dr Scafi read, and Professor took reflected upon, Canto 17. We are in the heaven of Mars, moving upwards through concentric circles of planets, where we meet Cacciaguida, who died before Florence turned, in Dante's view, to the bad. This is the chance for our poet to lament the moral decline of his beloved city and to make the third, last and most explicit reference in the Divina Commedia to his own exile.

Cacciaguida, 'gazing at the point to which all times are present', makes this prophecy to Dante:

Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta

più caramente; e questo è quello strale

che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta.

Tu proverai sì come sa di sale

lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle

lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale.

E quel che più ti graverà le spalle,

sarà la compagnia malvagia e scempia

con la qual tu cadrai in questa valle;

che tutta ingrata, tutta matta ed empia

si farà contr' a te; ma, poco appresso,

ella, non tu, n'avrà rossa la tempia.

Di sua bestialitate il suo processo

farà la prova; sì ch'a te fia bello

averti fatta parte per te stesso.

You will leave behind everything loved most dearly, and this is the arrow that the bow of exile first lets fly. You will learn how salty tastes the bread of another, and what a hard path it is to descend and mount by another's stairs. And what will most weigh upon your shoulders will be the wicked, dimwitted company with whom you will fall into this valley, who will become utterly ungrateful, mad and cruel against you, but shortly after they, not you, will blush. Of their stupidity the outcome will provide the proof, so that for you it will be well to have become a party unto yourself.

The literal translation, as in previous blog instalments, is by Robert Durling, though I haven't scanned it as he does. Shall find it impossible to read more 'literary' versions, having once seen the unreproducable beauty of the Italian.

Dante, as ever, is sure of his place in history, perhaps in all eternity. Caccaguida advises him to 'make manifest your whole vision', however galling that may be at first to those with a guilty conscience. And in fact he didn't suffer in his wanderings for long, coming under the wing of the Lombards and then finding his final haven in Ravenna.

His destination as the pilgrim of Paradiso, though, is the Empyrean, and a brief vision of God in the final Canto, 33, which must have had some impact on Cardinal Newman in The Dream of Gerontius. As we move towards the greatest luminosity, Dante coins ever more neologisms - 'trasumanar', 'transhumanizing', the most famous of all, was actually introduced in 1.70 and begins to be properly realised in Canto 30 - and finds ever more poetic ways of saying 'I lack the words to describe what I saw' (the last two are in 33, lines 54-7 and 120-2).

Finally, within 'three circles, of three colours and one circumference' - the Trinity - he sees 'what seemed to me painted with our effigy'. Does this mean that man/mankind is the last vision - that, as Professor Took put it, 'central to the Godhead is the human project', that neither God nor man should be alone? I love, as usual, his summation of Dante heading 'into a plenitude of proportionate understanding and ultimate love'.

My end is going to be another beginning, which I've described on the musical front on The Arts Desk: Ravenna, where Dante could not have been unaffected by the dazzling domes of light, whether in the blue-and-gold intimacy of Galla Placidia's Mausoleum - pictured at the top of the post - or the lofty heights of San Vitale.

On this visit, my second since leaving my last Interrailing pal in the city's youth hostel and making my first independent travel in 1982, I fell in love with Dante's final resting place. On, then, eventually, to those most heavenly of mosaics.