Showing posts with label Purgatorio. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Purgatorio. Show all posts

Thursday, 16 August 2018

Dante in Ravenna

The shady Zona Dantesca/del Silenzio around the poet's local church, San Francesco, quickly became my favourite refuge from the sun, if not the humidity, during my charmed time in Ravenna.

Of course there's the wonder of the tomb itself, a symbol of the ongoing homages to the master combining an 18th century exterior by Camillo Moriglia

with Pietro Lombardo's 1483 original, including a fine relief.

The story of Dante's bones and their various shakeups since he died in 1321 after three presumably tranquil years under the patronage of Guido Novello di Polenta - the Polentas of Ravenna are buried and have memorials like this one in Dante's parish church, San Francesco -

is a fascinating one, and it's comprehensively told in the displays of the Dante Museum on the first floor of the Centro Dantesco.

While there is an active courting of the non-Dante-reading public with some of the displays,

the right wall of the 'Inferno' room tells the history. On Polenta's orders, Dante's remains were placed in a marble sarcophagus lodged in the Chapel of the Madonna between the church and the convent. In 1519, alarmed that the Florentines wanted to reclaim the bones of their exiled poet, the monks remove them to a sepulchre installed within the walls. Another monk rediscovered them in 1677 and had them placed in a wooden box with this inscription.

The box in turn was walled up when the fraternity was banished in the Napoleonic invasion in 1810 and not discovered until 1863, when a workman came across them. Great celebrations in Ravenna, and a public display of the bones, announced on this poster,

before they were lodged in the 18th century chapel. In wartime, the bones were moved yet again

and finally back again. Amen.

The museum has one original room decorated in 1921 by the Dante Society of Montevideo (!)

and fine views over the cloister of San Francesco's monastery (the monks moved back in a century and a half after their evacuation).

The next courtyard belongs to the Palazzo Rasponi where Byron lived - there was a Byron conference going on in the rooms adjoining the museum - and here we gathered on the first morning for what turned out to be a pretentious 'homage to Dante' by a 'poet' and a loud band (who were better). I didn't stay for long; the audience, however, was more interesting. One of these ladies was with a strapping 'figlio di momma', not pictured.

If that Dante event was a disappointment, there was a major compensation later that afternoon - on my way back along the main shopping drag from San Vitale, I came across the splendid reciter doing all the voices from memory, giving us the whole of the canto about Cacciaguida.

I was hoping to see him again on subsequent days, but I didn't.

The square of San Francesco is a lovely one, lined by trees and a pretty garden on one side and with a very good cafe-restaurant under the arches on the other.

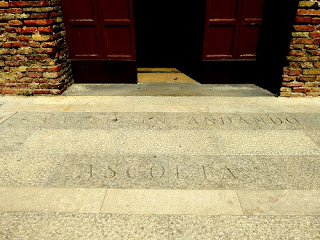

Our Virgil in the Warburg Dante classes, Dr Alessandro Scafi, was responsible for choosing the quotations from the Divina Commedia carved into the stones. He wanted a sense of a passage from profane to sacred as one approaches the central west door of the church, in front of which we read 'Va, e andando ascolta' - 'Go, and listen as you do so'.

'Venite: qui si varca', 'Come: here is the crossing', are the words of the angel in Purgatorio 19:43.

And then there are the beautiful last four lines of its final Canto:

Io ritornai da la santissima onda

rifatto si come piante novelle

rinovellate di novella fronda,

puro e disposto a salire le stelle.

(I returned from the most holy wave refreshed, as new plants are renewed with new leaves, pure and made ready to rise to the stars).

There is also a Dantesque inscription on the ex Casa del Mutilato on Piazza Kennedy, a Mussolini-era experiment from the years 1937-9 built in the demolished Jewish Quarter and now refurbished. Strictly speaking it's 'de l'alto scende virtù che m'aiuta'. 'from on high descends a power that helps me; line 68 of Purgatorio's Canto I.

The interior of San Francesco may seem a little gloomy compared to the mosaiced glories of other buildings in Ravenna, its sales table manned by two old ladies who had a little difficulty giving me the right change for the postcards I bought. But it has atmosphere, with its 22 columns of Greek marble and a splendid roof

and a treasure you might miss if you gave the building only a cursory glance: the crypt of Bishop Neon's fifth century original with a mosaic pavement now affected by Ravenna's rising water levels.

This only makes what you see through a grille below the high altar the more picturesque; and the goldfish are there for practical reasons, feeding on the algae which might otherwise destroy the mosaics.

That more or less concludes my Dante instalments. I don't want to leave him behind. I have yet to make headway with the dual-language edition of Vita Nuova, and I'll certainly return to the Scafi-Took spectacular next 'term' for the earlier Inferno classes I missed by joining late. As for the lead image, it's part of a splendid mural over one side of the boarded-up central market place, also featuring other Ravenna-connected celebrities. Insertion: a bit of classy graffiti elsewhere, presumably a take on Dante and Beatrice.

And there are several fine cafes and restaurants on the other side of the street, which the Ravenati frequent with their dogs - as regular a feature of the city as the bicycles.

Sunday, 17 June 2018

Ever upwards with Bach and Dante

You can see I'm in danger of being left behind on terra firma in both my big pursuits of the year, with four out of seven Bach cantatas to catch up on here - I'll deal with the other three alongside next today's in a future post - and four Dante lectures to comment upon, of which I missed one. Nevertheless I'll make some effort to be light and airy like the masters.

It seems I was premature in leaving Purgatorio behind in my previous Dante/Bach post: there turned out to be one more Warburg Institute class on the middle cantica. The most treasurable utterance, of many, that I took away from Professor Took, of many, was a very helpful summary of the Dantean essence in response to one of the questions in the discussion: 'Peope's lives are mixed, ambiguous in the extreme, simultaneously in hell, purgatory and paradise. In order to explore [the issue], he divides it out. The moment of truth lies somewhere in the unutterable complexity of the here and now'.

Even so, Dr Scafi prepared us for 'a difficult and allegorical Canto' (33, the last, of Purgatorio) in the shape of the final processional which represents the triumph of the church (sketched above by Botticelli, no less), complete with the four cardinal virtues, three theological virtues and Beast of the Apocalypse. The difficulties pale into insignificance once we reach Paradiso. Dante warns the slackers among us - and there must be many more now than in that religiously obsessive age - at the beginning of Canto 2 (with acknowledgment to Robert W Durling's literal translation):

O voi chi siete in piccioletta barca,

desiderosi d'ascoltar, seguiti

dietro al mio legno, ché cantando varca:

tornate a riveder li vostri liti,

non vi mettete in pelago, che forse,

perdendo me, rimarreste smarriti;

l'acqua ch'io prendo già mai non si corse;

Minerva spira, e conducemi Appollo,

e nove Muse mi dimostran l'Orse.

O you who in little barks, desirous of listening, have followed after my ship that sails onward singing, turn back to see your shores again, do not put out on the deep sea, for perhaps, losing me, you would be lost; the waters that I enter have never before been crossed; Minerva inspires and Apollo leads me, and nine Muses point out to me the Bears.

Despite the comfort of mythological and classical signposts, the Christian theology, albeit that Dante has such a singular take on much of it, is what makes so many of Beatrice's homilies rather hard for the contemporary reader. So is the assurance of a now outdated cosmology; it can't all be taken as poetic metaphor, after all. Nevertheless, the guidance of our Warburg Dante and Virgil (who has long disappeared from the scene in the Divina Commedia, of course), and the thoroughness of the notes to the Durling edition (of which the Paradiso volume runs to 873 pages) make the most difficult journey worthwhile.

The best of our two most recent classes, for me, has been in the discussions. I'm getting antsy: why should Piccarda Donati and the empress Constanza be in the lowest sphere, the moon, in Canto 3 (pictured above), simply because men snatched them out of their nunneries and forced them into unspeakable wedlock? And why does the narrative of Dante's Thomas Aquinas about St Francis seem so hard and charmless to us, expecting at least something of the goodly saint's conversation with nature?

Dante's Beatrice provides part of the answer when it comes to the two paradisical ladies in Canto 4: they merely appear in the moon, and actually adorn the first sphere, the Empyrean. It's a matter of conscience. Well, that's half satisfactory. And Prof. Took thinks that the narrator Dante is playing the serpent when he asks them if they don't desire a higher place. Smiling and joyful Piccarda replies that 'it is constitutive of this blessed to stay within God's will, and thus .our very wills become one' ('Anzi e formale ad esto beato esse/tenersi dentro a la divina voglia/per ch'una fansi nostre voglie stesse', 3.79-81).

As for Francis, the harshness is to do, as Prof. Took put it, with Dante's 'stringent selectivity' - he has an axe to grind with the Dominicans and their tendency towards luxury in opposition to the Franciscans, led by a man who took Poverty as his Bride. He's 'too angry', has 'too much of an agenda' to spend time on the birds and the beasts.

Bach doesn't always do the expected thing, either, though his line of communication is always direct thanks to the expressive power of music. His first Ascension cantata for Leipzig, 'Wer da gläubert und getauft wird' comes not with trumpets and drums but an exquisite halo of two oboi d'amore, a short if uplifting opening chorus and an affirmative tenor aria with ardent violin obbligato. Loveliest is the chorale for soprano and mezzo in imitation with dancing continuo support, as Brides of Christ complete with joyous 'eia's- irresistible when Rilling's soloists here are Arleen Auger and Carolyn Watkinson.

That fine alto distinguishes BWV 44, 'Sie werden euch in den Bann tun', with a superb aria alongside oboe and bassoon. The opening is surprising: two parts of the text run respectively as a duet for tenor and bass and a harmonically wayward chorus in faster tempo. The chorale for tenor here has a distinctly weird, chromatic accompaniment from bassoon, there are fabulous adventures from the bass line in the virtuoso soprano aria, verging on the Handelian, and the closing chorale is familiar from its similar setting in the Matthew Passion.

BWV 172, 'Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten!' for Whitsunday, is much more what one might expect for Ascension. It comes as no surprise to learn that its three celebratory trumpets, which go virtuoso-crazy in the bass aria (a good, if short alternative to Handel's 'The Trumpet Shall Sound'), were originally meant for a secular celebration, but they suit the celestial setting of the Weimar chapel (pictured below, no longer extant, alas) for which they were destined in 1714. The tenor aria offers some room for reflection, and a presumably deliberate harping on minor seconds in the 'weh' of 'wehet'.

Intimacy is apt for the Whitsun Monday and Tuesday cantatas, both of which begin with charming recitatives. BWV 173, 'Erhöhtes Fleisch und Blut", is another cantata adapted from a profane congratulatory set. It haas a radiant beginning (plus a non-chorale final number, unusual but not unique among the cantatas) and a lilting 6/8 tenor aria (beautifully sung on the Rilling set by his regular, Adalbert Kraus) with flute doubling first violin line to strong effect. The most original number, in which each of three verses, first for bass, then soprano, then the two together, is treated with increasing elaboration, is ruined by the only inadequate soprano I've heard on the Rilling set so far; let's hope she's a one-off.

BWV 175, 'Er rufet seinen Schafen mit Namen' captures the good-shepherd pastoral aspect with three recorders - and we're back to excellent soloists - Watkinson, Schreier, Huttenlocher - exchanged for two very florid trumpets before the finale choral reverts to the original colouring. Last night, in the only one of the three Gardiner cantata sequences I was able to catch over the Bach weekend at the Barbican, there was equal rustic beauty in the perfect correspondence between countertenor Reginald Mobley and Rachel Beckett and Christine Garratt on two transverse flautes for the aria 'Wohl euch, ihr auserwählten Seelen' in BWV 20. But I feel that's all I can write on the evening's cornucopia of riches for now, lest you feel drowned in BWV numbers. More anon.

Sunday, 6 May 2018

Dante in Eden, Bach after Easter

Maybe there was a part of me mildly disappointed by Dante's arrival in the Garden of Eden at the very top of Mount Purgatory for his crucial meeting with Beatrice. I guess I'd expected more description of the natural paradise à la Milton, whereas it's subordinate to allegory and rather too much theologising towards the end of Purgatorio. But then I missed the chance to hear Dr. Scafi and Professor Took spread their own special love for these Cantos, overrunning as I did on the last class devoted to Janáček's From the House of the Dead (we had to see two acts of Chéreau's production, and even the extra time I'd allocated overran).

Certainly, though, the official leavetaking speech of Virgil is moving, and concise. I ought to reproduce it here so that, like the examples quoted in my previous Dante/Bach entry, I can try and memorise the Italian when I have time. Translation once again the literal but effective one by Robert M Durling.

in me ficcò Virgilio li occhi suoi,

e disse: "Il temporal foco e l’etterno

veduto hai, figlio, e se’ venuto in parte

dov’io per me più oltre non discerno.

Tratto t’ ho qui con ingegno e con arte;

lo tuo piacere omai prendi per duce;

fuor se’ de l’erte vie, fuor se’ de l’arte.

Vedi lo sol che ’n fronte ti riluce;

vedi l’erbette, i fiori e li arbuscelli

che qui la terra sol da sé produce.

Mentre che vegnan lieti li occhi belli

che, lagrimando, a te venir mi fenno,

seder ti puoi e puoi andar tra elli.

Non aspettar mio dir più né mio cenno;

libero, dritto e sano è tuo arbitrio,

e fallo fora non fare a suo senno.

Per ch’io te sovra te corono e mitrio"

Virgil fixed his eyes on me

and said: "The temporal fire and the eternal

have you seen, my son, and you have come to a

place where I by myself discern no further.

I have drawn you here with wit and with art;

your own pleasure now take as leader: you are

beyond the steep ways, beyond the narrow.

See the sun that shines on your brow, see the

grasses, the flowers, and the bushes that here the

earth brings forth of itself alone.

Until the lovely eyes arrive in their gladness

which weeping made me come to you, you can sit

and you can walk among them.

No longer await any word or sign from me: free,

upright and whole is your will, and it would be a

fault not to act according to its intent.

Therefore you over yourself I crown and mitre.

The interrupted dialogue between Beatrice and Dante is certainly unusual. At first, 'regal and haughty in bearing, she upbraids him, and only deigns eventually to show the warmth he craves, finally smiling towards the end of the last Canto, 33. On with the summer term, anyway, where our Dante and our still present Virgil at the Warburg will lead us through Paradiso.

It seems ages since we last met for the final Purgatorio class I was able to attend; and it's been too long since I actually listened to a Bach cantata on the Sunday for which it was intended. I have the five after Easter to deal with here, and since sharp memory of all of them fades - I have the notes in my book still - I must head only for the high points, and three arias especially.

BWV 42, 'Am abend aber desselbigen Sabbats' begins with an almost Handelian sinfonia - the only cantata to start that way in Bach's second Leipzig cycle - before the tenor introduces the opening text over throbbing strings (perhaps the beating hearts of the Disciples as Christ walks among them). And then, and then, one of the loveliest arias in all the cantatas, surely, and that's saying something (one would probably have to include at least two dozen in the top list). The first of the two oboes made me want to get my long-neglected instrument out of its case. Gardiner describes how he found 'Wo zwei und drei versammlet sind' 'unbearably pained and sad at our first performance, and far more serene and consoling at the second'. Can't find a recording to match Rilling's two oboes and mezzo Julia Hamari, so here's the whole thing from the cycle to which I'm adhering. The aria is at 6m42s.

BWV 85, 'Ich bin ein guter Hirt' starts with bittersweet pastoral and flows beautifully. BWV 146 begins originally with a surprising adaptation of the D minor Harpsichord Concerto - brilliantly rendered, incidentally, on the Jean Rondeau disc we nominated as BBC Music Magazine concerto disc of the year, and I'd have been happy had it won. Wonder of wonders, there's even a film of the first movement to go with the recording on YouTube. If, like me, you're not usually excited by the harpsichord, this should help you change your mind.

The cantata continnues with a slow, astringent choral movement, also concerto-based. It has the next ineffable aria of my three, 'Ich säe meine Zähren', conjoined with a very expressive recitative, also for the soprano, haloed by sustained strings. Helen Donath is the best possible substitute for Arleen Auger, Rilling's most frequent soprano. One wonders if Mozart's exquisite woodwind ensemble writing stemmed from Bach - nothing could be lovelier than the quartet of flute, two oboes d'amore and bassoon on the bass line. Because I don't actually like Rilling's organ in a couple of stops, I've chosen Gardiner for the complete recording. Recit and aria are at 24m13s

It's a contrasting expression of sowing with tears and reaping with joy. These 'twixt-Easter-and-Ascension cantatas seem much to do with earthly sorrows, heavenly promise, but maybe that's the essence of the Lutheran texts throughout. I'm going to pass swiftly over BWV 166, with its striking short phrases for oboes and violins around the bass's 'Wo gehest du hin?'s and another lovely weave of solo violin and oboe around the tenor aria, and end with BWV 87, 'Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten'. The winner here is another alto aria, 'Vergib, o Vater, unsre Schuld', with elaborate writing for oboes da caccia, a rising bass line and one of Bach's most involved middle sections, winsome when it breaks out into triplets. The mezzo/alto needs superb breath control here. Alas, no Rilling on YouTube, and some weedy countertenors are no substitute, so I had to make do with Koopman - too slow, I think - because of Bogna Bartosz at 2m44s.

The tenor's recit ties in nicely with Dante's far from easy journey to the top of Purgatorio: 'When our guilt climbs all the way to heaven, you see and know my heart, which hides nothing from you; so seek to comfort me'.

Labels:

Bach Cantatas,

Beatrice,

BWV 146,

BWV 166,

BWV 42,

BWV 85,

BWV 87,

Dante,

harpsichord,

Helmuth Rilling,

Jean Rondeau,

Julia Hamari,

Purgatorio,

Virgil

Thursday, 5 April 2018

Bach and Dante over Easter

The Bach cantata pilgrimage with Rilling and company came to a halt over Lent, for obvious reasons. And since the only Palm Sunday cantata, BWV 182, was among the last I reached in my 2013 attempt to make a whole year of cantatas, Easter weekend marked the pick-up point. First, though, an essential Passion for Good Friday, since this year I didn't get to hear one live (the nearest I came was the unforgettable Lucerne staging of Schumann's Scenes from Faust). I have the Britten set of the St John on LP, unheard until now, with its bold reproduction of Graham Sutherland's Northampton Crucifixion on the cover, and it proved a very moving listening experience.

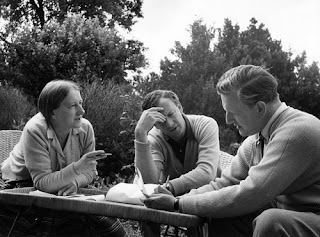

Having started with another boxed set I picked up recently in a quest to try and take unfashionable large-scale Bach seriously, Karajan's St Matthew Passion, and given up when faced with the sludge and the dim sound - back that goes to another charity shop - Britten's is a whole new world of biting passion and inscaped sadness. It's sung in English, with Peter Pears having worked on the recitatives and Imogen Holst collaborating on the rest; Colin Matthews writes briefly but eloquently on the changes in an essential booklet note. And I've been reading Imogen H on Britten and Byrd recently; what a superb clarifier she was (pictured below with Britten and Pears in the Red House garden).

Pears's burning delivery - the famous setting of Peter's weeping is as searing as any - makes it work. And there's plenty of thrust in the meaning from the Wandsworth School Boys' Choir - really, no extra voices? - and the superb soloists. John Shirley-Quirk helps realise Britten's special spirituality in the last bass aria with chorale, and Alfreda Hodgson is peerless in both Parts, much abetted by the English Chamber Orchestra oboes in No. 11. A great mezzo, easily the equal of Janet Baker and yet so overlooked by comparison.

Later I turned to another LP box I picked up recently, Britten's 'new concert version' of Purcell's music for The Fairy Queen, in which Hodgson sings Mopsa to Pears's Corydon (no all-male bad camp here, then, but plenty of esprit). Again, the stylishness and engagement leap out over a distance of 45 years, and I like what Britten does with the messy hybrid better than any other version. I've now ordered up his Schumann Faust-Szenen with Fischer-Dieskau as a third LP set to make a handsome trilogy.

Easter Day, Monday and Tuesday brought with them new cantatas to hear, so finally it was back to Rilling. 'Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret,' BWV 31, was composed by the 30-year old Bach for Weimar - the size of it suggests the original venue as not the court chapel but the main parish church known as the Herderkirche where we were lucky to attend an Easter Sunday service back in 2015, looking on the splendid Cranach altarpiece -

and probably reused in Leipzig. Gardiner suggests a parallel between the five-part chorus and the Gloria of the B minor Mass, down to the slowing of tempo and rest for the brass in the middle. It's exactly what one would expect for a 'Christ is risen' Cantata, though the ensuing recits are perhaps more striking in their word-painting than the bravura arias. There's a sublime trumpet descant to the final chorale.

Our Easter Sunday anthem this year, by the way, was Hadley's 'My beloved spake,' which we all used to love in the choir of All Saints Banstead - I realise it also enable me to recite this bit of the Song of Solomon - and which was sung on Sunday by the choir of St Paul's Cathedral. So we went there through the drear and heard the music only from a great distance, among masses of tourists. Still, Hadley's juicy harmonic shifts and two big blazes made their mark. I'm hoping close friends Juliette and Rory will choose it for their wedding this summer.

Most fascinating on the Bach front is the extreme contrast between the Easter Day jubilation and the inwardness of 'Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden,' BWV 6, composed for 1725's Easter Monday in Leipzig. The comparison here in the opening chorus is even more marked, with the bittersweet genius of 'Ruht wohl' at the end of the St John Passion, C minor key and sarabande movement included.

How wonderful the harmonies of the two oboes and oboe da caccia and the power of the chorus in Rilling's superlative performance; likewise the oboe da caccia's solo in counterpoint with mezzo Carolyn Watkinson, a singer I always liked and who appears in the Rilling Bach cantatas for the first time, and the piccolo cello against Edith Wiens (another unexpected name in the set) singing the central chorale. Profound music throughout in a great performance.

Gardiner is a thoughtful commentator again; he compares the contrast between the absence of Christ in a light-diminished world and a holding on to Word and sacrament, a contrast between dark and bright, with Caravaggio's first representation of the Supper at Emmaus, pictured above; it made me look up the second, where Christ has a beard.

Still, although it's less pertinent here (daylight is preferred to the night setting), Titian's representation, often overlooked in the Louvre because it hangs opposite Leonardo's Mona Lisa and currently in the stunning Charles I exhibition at the Royal Academy, is the one closest to my heart. Such gorgeous coloured silks, such an amazing composition.

Easter Tuesday's cantata is a little satyr-play by comparison with the Big Ones; it seems that a Telemann opening chorus was added, probably in performances after Bach's death. 'Ich lebe, mein Herze, zu deinem Ergötzen,' BWV 145, putatively reworks secular numbers lost to us. It dances its nine-minute way in a delicious opening duet with solo violin and a tenor aria with trumpet solo. A concert of all three cantatas would be as good a demonstration as any of Bach's phenomenal emotional range.

Dante's encyclopaedic frame of reference, in the meantime, continues to stun. Frail follower that I am, I missed the climactic Warburg class on Purgatorio, in which I'm told Dr Alessandro Scafi read Dante's meeting with Beatrice in the Garden of Eden with special tenderness; I'd only just back from Lucerne last Monday, and the extra half hour I'd promised the Opera in Depth students so that we could see the second and third acts of From the House of the Dead in Chéreau's production ran over; a furious pedal from Paddington to Bloomsbury would still have made me miss at least ten minutes of the class.

Anyway I shall reach the top of Purgatory Mountain under my own steam, and meanwhile I've had time to reflect on what my dual-language Dante edition calls 'the great expositions of doctrine at the centre of the Purgatorio'. That therefore means at the centre of the entire Divina Commedia. They appear in Cantos 15-18, and in our first class on the second instalment of the mighty work, Dr. Scafi and Professor Took chose three key passges from two of these Cantos. I'm going to gloze superficially in order, starting most skimmingly with the sharing of heavenly goods, which Dante adapts from Gregory the Great. Earthly ones, according to Dante's Virgil, cannot be shared without a lessening for each sharer; our democratic societies with their libraries, museums and hospitals, albeit under threat, would deny that, as translator Robert Durling points out.

Nevertheless the sharing in Purgatory which began in Canto 2 with the communal hymn in the boat bearing Dante's beloved composer Casella and others is one of the loveliest things about this second book after the total solipsism of the characters in hell. The language strikes me as especially beautiful in these central Cantos, so I'm going to quote at well with Durling's literal translation to follow.

...per quanti si dice più li 'nostro',

tanto possiede più di ben ciascuno,

e più di caritate arde in quel chiostro.

For the more say 'our' up there, the more good each one possesses, and the more charity burns in that cloister (15, 55-7).

Quello infinito e ineffabil Bene

che la su è, così corre ad amore

com' a lucido corpo raggio vène.

That infinite and ineffable Good which is up there runs to love just as a ray comes to a shining body. (15, 67-9).

E quanta gente più là sù s'intende.

piu v'è da bene amare, e piu si v'ama,

e come specchio l'uno a l'altra rende.

And the more people bend toward each other up there, the more there is to love well and the more love there is, and, like a mirror, each reflects it to the other. (15, 73-5)

Well, we can at least aspire to that down here, can't we? 'We must love one another and die'.

By the way, I'm typing out the Italian in the hope that I can memorise more here, as I have of three-line segments of the Inferno. I don't really know where to start or end in Marco Lombardo's explanation of the relationship between fate/the stars and free will in Canto 16 (the soul trying to cleanse himself in the murk is illustrated by Doré above). But I'll try to keep it down. This is the beginning of Marco's exposition to Dante.

Alto sospir, che duolo strinse in 'uhi!'

mise fuor prima; e poi cominciò: 'Frate,

lo mondo è cieco, e tu vien ben da lui.

Voi che vivete ogne cagion recate

pur suso al cielo, pur come se tutto

movesse seco di necessitate.

Se così fosse, in voi fura distutto

libero arbitrio, e non fora giustizia

per ben letizia, e per male aver lutto.

A deep sigh, which sorrow dragged out into 'uhi!', he uttered first, and then began: 'Brother, the world is blind, and you surely come from there. You who are alive still refer every cause up to the heavens, just as if they moved everything with them by necessity. If that were so, free choice would be destroyed in you, and it would not be just to have joy for good and mourning for evil. (16, 64-72)

'Lume v'è dato a bene e a malizia,' 'a light is given you to know good and evil,' Marco continues, tracing the origins with a lovely image which follows the feminine gender of 'anima',

Esce di mano a lui che la vagheggia

prima che sia, a guisa di fanciulla

che piangendo e ridendo pargoleggia,

l'anima semplicetta, che sa nulla,

salvo che, mosso da lieto fattore,

volontier torna a ciò che la trastulla.

Di picciol bene in pria sente sapore;

quivi s'inganna, e dietro ad esso corre

se guida o fren non torce suo amore.

From the hand of him who desires it before it exists, like a little girl who weeps and laughs childishly, the simple little soul comes forth, knowing nothing except that, set in motion by a happy Maker, it gladly turns to what amuses it. Of some lesser good it first tastes the flavour; there it is deceived and runs after it, if a guide or rein does not turn away its love. (16, 85-93)

This is a fine amendment of Augustine's concept of original sin: Dante is telling us that human nature as such is not corrupt, but simply makes bad choices (by the way, God, please send me a Virgil who looks like Hippolyte Flandrin's above). No wonder Dante wanted to reinforce and expand on Marco's words with Virgil's in Cantos 17 and 18. Although the language is drier, more theoretical, I love these lines:

'Né creator né creatura mai,'

comincio el, 'figliuol, fu sanza amore,

o naturale o d'animo, e tu 'l sai.

Lo natural è sempre sanza errore,

ma l'altro puote errar per male obietto

o per troppo o per poco di vigore.

'Neither Creator nor creature ever,' he began, 'son, has been without love, whether natural or of the mind, and this you know. Natural love is always unerring, but the other can err with an evil object or with too much or too little vigour. (17, 91-6).

More on love natural and elective, with further subdivisions, is to be found in the continuation of Virgil's observations in Canto 19, but this is probably more than enough to try and digest for now. Mighty Dante - intellect and poetry perfectly conjoined to make independent thought that is anything but simplistically moralising.

Wednesday, 21 March 2018

Communal song and prayer in Dante's Purgatory

'Cantavi tutti insieme con una voce' - 'they were all singing together with one voice'; 'Quest'ultima preghiera, segnor caro, già non si fa per noi, ché non bisogna, ma per color che dietro a noi restaro' - 'this last prayer, dear Lord, we do not make for ourselves, since there is no need, but for those who have stayed behind'. Welcome to the shared experiences of Dante's Purgatorio. The singing souls in the boat with an 'angelic pilot,' steering with wings, and the proud who hope to be redeemed but are weighed down by stones on their shoulders share a selfless communion.

As our Dante to the Virgil of Dr Alessandro Scafi at the Warburg Institute's free course on the Divina Commedia, Professor John Took, reminded us this week, 'no one in the Inferno says "this is for them," only "this is for me" ', and the only kind of association there is in implicating others in one's own catastrophe. 'There is no creative sharing in the Inferno'.

Yet somehow we shared Dante's horrified savour of being there - all those fascinating individuals cognisant of their guilt but unable to repent. In one of many surprising parallels with a very different text I'm working on with students in this term's Opera in Depth, Dostoyevsky's From the House of the Dead (or Notes from a Dead House, as the translation I'm now reading, that of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, has it), the author who shared the fates of the most hardened criminals in Siberia puts his finger on the plight of the damned in speaking of one of the other prisoners: 'he was fully aware that he had acted wrong...but though he knew it, he seemed quite unable to understand the real nature of his guilt'.

With Dante, one can take any number of variations on that theme, so superbly realised are the figures as dramatic characters, but it's such a relief to see the light as Dante and Virgil go through the centre of the earth and find themselves on the other side, in the Antipodes, with a different starscape. Canto 1 of Purgatorio dwells so loving on the beauty and wonder of the sky, and paints a landscape with rushes at the foot of the mountain to be climbed,

but in between we meet Cato, guardian of Purgatory,

and in Canto 2, an even more 'real' personality - the composer Dante had known (and we don't, despite a 20th century namesake) whom he addresses so warmly as 'Casella mio'.

Yesterday evening produced an interesting contrast. On the one hand we had the bas-reliefs of humility on the terrace of Pride

and its stone-laden incumbents delivering Dante's version of the Lord's Prayer, which Dr. Scafi had students read in Arabic, Mandarin, French and Spanish, a tribute to the insurance magnate Marco Besso who in 1908 produced a book with the same text in multiple languages; Dante provides a gloss within the poetry on the meaning of the text.

On the other we were back to living figures, as it were: Omberto Aldobrandesco, who wants to humble his earthly pride in family but can't resist rolling out the splendid name - as Dr Scafi did, with relish - and Oderisi, a leading manuscript illuminator. This leads Dante, through Oderisi, to a disquisition on the transience of fame both in art - Cimabue has already yielded first place to Giotto - and in literature, 'one Guido', Cavalcanti, has taken the honour of 'first poet' from another, Guinizelli.

'Forse è nato chi l'

The attitude to the artist's task is avoiding hubris but at the same time 'implementing the properties of selfhood'. So un-Medieval this, so modern. The artist's destiny is to be capable of carrying out what he or she is called to do. And that means embracing human nature in all its complexity. Dante is a dramatic poet, not a dry moralist; he is greater than the parameters of his age's religious thought, and that's why we still read him. I was going to wind into this the introductory Purgatorio class's selection of lines which so beautifully render the difficult question of free will, but I can see I've gone on far too long, so that's for another time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)