Forgive the note of unusual negativity in a blog which is

mostly about sounding enthusiasms: this is a post about why I’m not going to

the movies to see Keira Knightley as Anna Karenina, and why I’ve not returned to

Keith Warner’s Royal Opera production of Wagner's Ring after an underwhelmed first visit. The

positives are rather retrospective, but ideals are difficult to shift once

you’ve witnessed them. There can only be new experiences of visions which work very differently but on the same level or else disappointments in store.

As for Anna Karenina, first of course you should read (or

re-read: note to self) Tolstoy’s novel, and

then head not to the cinema but to DVD to see the old BBC serialization

with an unforgettable central performance by Nicola Pagett (pictured above).

Why? Most obviously because the leisure of a multi-parter is always going to be more apposite to Tolstoy’s panorama than a film, even one that’s more than the standard 90 minutes long (a notable exception is Sergei Bondarchuk’s epic, still selective take on War and Peace). The Garbo version, by the way, is beyond bad. But above all I think the BBC casting of Tolstoy's protagonist was so right, possibly because for me as a teenager Pagett WAS Anna before I came to read the book, and even the reading didn't change that. A revisit suggests she’s still apt in so many ways – not least for the nervous intensity, the hectic flushes, which we now know were part of this talented, bipolar actress’s burden in real life. Pagett’s is a vulnerable heroine for whom you want the best, even when you know she’s doomed not to realize it.

The BBC series also gave proper weight to the parallel, equally significant strand of Tolstoy’s self-portrait – following bits of himself projected into both Prince Andrey and Pierre in War and Peace – as Levin. When I heard that the new film doesn’t bring Levin and Anna together, as they must be brought in any adaptation, that was another nail in the coffin of its reputation.

Of course the 1970s television production values were not as high as they’ve become in recent classic serials: Bleak House and Little Dorrit being atmospheric good examples, the recent Great Expectations a misapplication of misty gloom (and vanity casting) over the vitality of Dickens’s novel. But when the performances are as good as they were in the BBC Anna – and that includes Stuart Wilson, Eric Porter and Robert Swann – they overcome the creaky sets and garish studio lighting. A return to the BBC War and Peace, on the other hand, proved disillusioning: though Anthony Hopkins plays Pierre with extraordinary nuance, Morag Hood’s Natasha is too old for the impetuous teenager and lacks charm throughout. The 70s hairstyles, too, are more than a circumstantial liability.

Reports from trusted sources have suggested that many of the

major drawbacks in the Royal Opera’s Ring revival still loom large. Not that I

probably could have got a ticket even if I wanted to: the house was not giving any to The Arts Desk or any online reviews site, and getting a paid seat was going to be

next to impossible. But on my previous visit I hadn't taken away any favourable impressions of the way Keith Warner swilled around a lot of half-cooked ideas, not at least beyond Rheingold, which is in any case

a rather theoretical box of tricks and in this case promised more than the rest delivered. And Warner’s real weakness was to pay too

little attention to the chemistry of all the crucial one-to-ones; this is where

any great Ring production, whatever you think of its mises-en-scene, makes its

mark.

I’m glad if Pappano has more grasp of the oceanic tides than back in 2006-7, and if great Bryn now has the strength to make it as Wotan and Wanderer (he was tired out by the end of Walküre when I saw it, but still a major reason for going). Yet while Covent Garden has done right by Sue Bullock, as it should have in the first place when the house cast Lisa Gasteen, she of the shot top, as Brünnhilde, the Siegfried problem continues: Stefan Vinke makes a horrid noise, or did when I heard him labour his way through Proms performances of Mahler’s Eighth and Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass. I wouldn’t hold out much for his skill as an actor, either. (UPDATE - 11/2/2019 - how wrong I was on that count, seeing him as the Siegfried Siegfried this season. Fabulous forging scene too)

I’m glad if Pappano has more grasp of the oceanic tides than back in 2006-7, and if great Bryn now has the strength to make it as Wotan and Wanderer (he was tired out by the end of Walküre when I saw it, but still a major reason for going). Yet while Covent Garden has done right by Sue Bullock, as it should have in the first place when the house cast Lisa Gasteen, she of the shot top, as Brünnhilde, the Siegfried problem continues: Stefan Vinke makes a horrid noise, or did when I heard him labour his way through Proms performances of Mahler’s Eighth and Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass. I wouldn’t hold out much for his skill as an actor, either. (UPDATE - 11/2/2019 - how wrong I was on that count, seeing him as the Siegfried Siegfried this season. Fabulous forging scene too)

The point is, if you're keen to experience the whole marathon for its own sake, your money will at least have been decently spent. It might be worth while tuning in to Radio 3, currently halfway through its broadcasts from the Royal Opera. But the Ring remains, for me, the sum of the great cycles I’ve seen which worked: Chéreau’s incendiary Bayreuth Centenary staging

– my way in as watched, one act per week, on TV during my student years;

Kupfer’s first take, which I was lucky enough to see at Wagner’s home shrine,

and if I never get there again, I’ll at least have had my vision; and the

Richard Jones production at Covent Garden. Not all of it worked, but there Jones's radical ideas resonated throughout the four operas as Warner's much less rigorous rattlebag did not (and Jones's Siegfried was sheer genius). Even the Phyllida Lloyd staging for ENO had

unforgettable hits among the misses – I nearly left her Valkyrie after Act One, but Lloyd

upped its game from Brünnhilde’s annunciation of death to Siegmund onwards, and

the Twilight was inspired as a production from start to finish.

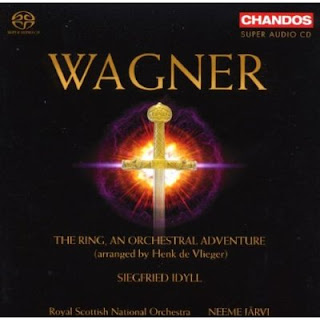

Anyway, talking of potted adaptations, I wonder what we

shall make of Henk de Vlieger’s 60-plus minute symphonic tour of Ring

orchestral highlights, due from the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the excellent

Mark Wigglesworth tomorrow night (and already espoused by Neeme Järvi and the

Royal Scottish National Orchestra on Chandos, a recording I have yet to hear).

On Tuesday with the BBCSO course students, I had one hour on Tippett’s Triple

Concerto, the first work in the concert – triggering a heated debate of pros

versus cons, with me somewhere in the middle – and one on the essence of the

Ring, with glimpses of the beginning and the end and in between, a couple of

selections from the momentous later stages of Rheingold and Walküre to deal with transformation/dramatic introduction

of the leifmotifs, and a gallery of nature pictures – water, air, fire and

earth.

Those should all be there tomorrow, but will the experience add up? Sometimes charisma can make it work - I love mad Stokowski's 'symphonic syntheses' from the Ring, Tristan and Parsifal, especially in his portamenti-laden Philadelphia recordings from the 1930s. Here's his take sans voices on Act Three of Parsifal.

As for Wigglesworth's Wagner (and Tippett), if you can't be there at the Barbican, the concert is broadcast live on Radio 3. STOP PRESS (20/10): It worked, it truly did (and the Tippett was compelling, too). Listen to the concert for the next seven days here and read the Arts Desk review here.

Those should all be there tomorrow, but will the experience add up? Sometimes charisma can make it work - I love mad Stokowski's 'symphonic syntheses' from the Ring, Tristan and Parsifal, especially in his portamenti-laden Philadelphia recordings from the 1930s. Here's his take sans voices on Act Three of Parsifal.

As for Wigglesworth's Wagner (and Tippett), if you can't be there at the Barbican, the concert is broadcast live on Radio 3. STOP PRESS (20/10): It worked, it truly did (and the Tippett was compelling, too). Listen to the concert for the next seven days here and read the Arts Desk review here.

.JPG)